Doctor Who: “Death In Heaven”

In the end, “Death In Heaven” is neither a Master story nor a Cybermen story. Like the rest of the season, the finale is really the story of the Doctor, Clara, and Danny. The episode takes a somewhat circuitous path to its final section—the UNIT business on the plane isn’t superfluous, but it could easily have been condensed—but as soon as the Doctor joins Clara and Danny in the graveyard, the story snaps into focus. This is a finale that bristles with ideas: who the Doctor is, what his relationship is with the Master, what role soldiers have in Doctor Who, why the Doctor and Clara can’t help but lie to each other, and on and on. As is so often the case with the show’s two-parters, the slightly padded “Dark Water” gives way to a finale that feels overstuffed even with a full hour to work with. If this finale reveals an essential issue with last week’s entry, it’s that “Dark Water” could have done a better job focusing the audience’s attention on the most crucial elements of the two-parter’s story; as it is, I’ll admit it took a second viewing of “Death In Heaven” to appreciate fully what this finale most wants to say.

Some elements of the finale really are just throwaways, most obviously Clara’s attempt to pass herself off as the Doctor. There are a lot of good secondary reasons why the episode would do this: to get one hell of a misleading moment—“Clara Oswald never existed!”—into the trailer, to squeeze in some rapid-fire continuity references, to give Clara something to do while the rest of the episode falls into place, and to redesign the opening credits in one of the franchise’s more inspired in-jokes. What there isn’t really is a truly vital reason for the episode to do this, although “Death In Heaven” comes close. On some level, Clara’s subterfuge is the final step in her season-long evolution, taking her from the terrified human taking on the Half-Face Man in “Deep Breath” to the surrogate Doctor of “Flatline.” That could work, only those 3W scenes never play as character moments; all those fun ancillary reasons end up feeling more important than whatever Clara-specific point the episode wants to make. Steven Moffat’s scripts so often veer between clever and “clever,” and these scenes are just a tad too arch for their own good. Even then though, Danny Pink brings clarity to the proceedings: His sad affirmation that Clara is indeed a great liar does add some weight to this sequence.

With Danny, “Death In Heaven” realizes a crucial point about the Cybermen. Whatever the audience might know intellectually about the Cybermen’s true nature, an army of Cybermen is really just a bunch of killer robots, but a single Cyberman? Now that is a nightmare. This episode isn’t nearly a Cybermen story to the same extent as, say, “The Next Doctor” or “Nightmare In Silver,” yet this is the first time since way back in “Rise Of The Cybermen”/“The Age Of Steel” that the new series has really attempted to confront the body horror that the Cybermen represent. This story is more nuanced in its exploration of the Cybermen than was “The Age Of Steel,” in which shutting down the creatures’ emotional inhibitors caused them to literally explode from pain. In keeping with the visuals of the cloud-choked Earth, “Death In Heaven” paints in more muted colors, trusting Samuel Anderson’s performance—with an assist from makeup that is horrifying without being actively revolting—to convey how the conversion process has robbed Danny of the hope that once made life worth living, leaving behind only the pain.

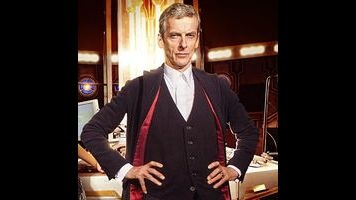

But then, as the Doctor argues, pain is what separates us from the monsters; certainly, it’s what he believes separates him from the other renegade Time Lord who stole a TARDIS and ran away from home. This sentiment is one of several incisive 12th Doctor moments that “Death In Heaven” provides. There is no aspiration here, but merely the grim recognition that to live is to hurt others, be it physical, psychological, emotional, or whatever else. The Doctor’s every attempt to play the hero forces him to make terrible decisions, to prioritize the possible survival of some over the certain death of others. As he wistfully observed at the end of “Mummy On The Orient Express,” “Sometimes the only choices you have are bad ones, but you still have to choose.” Peter Capaldi has brought so much to the role in his first year, and one of his particular assets is the anguish he brings to the Doctor’s worst moments. The realization that the only way to save Earth is to sacrifice whatever’s left of Danny definitely qualifies. This Doctor doesn’t make a performance of his grief in the same way his immediate predecessors sometimes did, but—whatever he might claim—he still feels every dreadful consequence of his actions. That’s what separates him from the Master’s insanity.

“Death In Heaven” is new Doctor Who’s best Master story, though since the competition consists of “The Sound Of Drums”/“Last Of The Time Lords” and “The End Of Time,” I sense the phrase “by default” in the vicinity. (All right, fine, there’s also the final 10 minutes of “Utopia,” which admittedly is pretty excellent.) This definitely isn’t a small-scale story, what with every person who has ever died coming back as a Cyberman, but this story doesn’t aspire to the kind of absurd, operatic heights of the two John Simm Master stories, and this allows “Death In Heaven” to maintain a narrative focus that eluded the previous Master adventures. For all the epic contours of her plan, what Missy really hopes to achieve is stunningly simple: She just wants the Doctor to admit, for once, that they aren’t so different. The Master is a character defined by contradiction—some intentional, some the byproduct of over four decades of inconsistent writing—but an essential paradox is that, going back to Roger Delgado’s original, the Master wants to conquer the universe to bring order to it, yet the character embodies chaos and insanity. Missy has a point: Sure, we’d need to soften the wording a little, but is that really so dissimilar from the Doctor’s actions at various points over the years? Is all that really separates them the fact that the Master is willing to make the hard—well, insane—choices necessary to build the Doctor an army with which he can set right every wrong in the universe?

That’s the dilemma the Master presents the Doctor with here, and it serves as a culmination to the question the Doctor has spent the season asking, as the flashbacks helpfully remind us. This is all a far more successful version of what “Journey’s End” was trying to do with Davros, not to mention a more disciplined spin on the 9th Doctor’s moral dilemma in “The Parting Of The Ways.” Both of those stories plunged Earth into such mortal peril and casually killed so many people en route to the Doctor’s moment of crisis that the character’s indecision risked making him look feckless. Here, as bad as the situation is, the global situation is still just about under control, as the Cybermen remain in a holding pattern. The climax of “Death In Heaven” is an intensely personal one, defined not by planetary peril but by the Master’s desperation to get her friend back, by Danny’s struggle to remain human, and by the Doctor’s attempt to understand once and for all just who he is. The eventual answer that the Doctor reaches—that he’s an idiot, one just passing through, learning and helping where he can—is a self-effacing one, and perhaps it’s own kind of rhetorical dodge, but, like so much of this Doctor’s tenure, it feels in keeping with the basic truths that define all Doctor Who. Presidents and officers, heroes and good men, and even bad men are defined by rules, by expectations, but that isn’t the Doctor, not really, not at his core. He just tries to do what’s right in the moment, and that ought to be enough.

The reason that’s the case goes back to what really separates the Doctor and the Master, and it’s on this point that Michelle Gomez’s incarnation most closely aligns with John Simm’s: The Master is so obsessed with controlling everything that she always, always gets done in by the details. As the Doctor has made clear more than once this season, he adopts a big-picture view so that his friends don’t have to, but even this more aloof incarnation is capable of seeing the little things when he really tries to. He can defy the Master and refuse her army because he noticed what she didn’t, what she couldn’t: The one soldier in all the world who wasn’t following her orders. Yes, the Doctor’s faith in Danny and Clara is the latest articulation of that dratted power of love theme, and I’m not going to disagree with anyone who finds cloying the phrasing of the “Love is a promise” line, but I’d submit that this season has earned that unsubtle moment with how it has developed Clara and Danny’s relationship, how it has explored this more alien Doctor, and how it contrasts that moment with the heartbreak still to come.

It’s here too where “Death In Heaven” makes the season’s closing argument for why Doctor Who needs soldiers. As Danny says, his final act as a Cyberman is neither the order of a general nor the whim of a lunatic, but rather the promise of a soldier: “You will sleep safe tonight.” The Doctor’s pacifism is a funny thing, more honored in the breach than in the observance, and a worldview born as much of self-loathing and moral grandstanding as anything else. For all this Doctor’s efforts to jettison the clutter of contradictions that defined his predecessors, his antipathy for soldiers has felt like a particularly unfair bit of posturing, a byproduct of his continued uncertainty over his own declaration. He spent a season declaring who he is, but it’s only at the end of “Death In Heaven” that he knows for sure, and the realization that he’s an idiot is telling. After all, there’s an innocence to idiocy, a conscious refusal to consider the larger consequences of his more immediate actions. The Doctor’s attempts to save his own soul and that of his companions create the need for those who are less concerned with their own virtue, but rather the protection of others.

That’s why the Doctor needs soldiers. That’s what Danny is there to do, and that’s what Doctor Who’s most legendary soldier returns to do. The final confrontation with Missy—well, not final, because if we’ve learned anything by now, it’s that the Master always has a way out—is such a drastic departure from the end of “Last Of The Time Lords.” Gone is the Doctor’s desperate need to save the only other Time Lord in the universe. The potential restoration of Gallifrey probably has something to do with that, but I would argue only indirectly, only in the sense that this long-term hope has helped fueled this massive pivot from the 10th Doctor to the current incarnation. The 10th Doctor was desperate to save the life of the Master at any cost, if only because he could not bear to be alone; yes, he too wanted to stop Francine Jones from lowering herself to the Master’s level, but he did so from an implicit moral high ground. Here, the Doctor offers no pretense, as he will kill the Master if only to prevent Clara from doing so. As the Master observes, the Doctor does so to save Clara’s soul, but who will save his? If the Master had any sense of her and the Doctor’s shared history, she really ought to have known who would come to the Doctor’s rescue in his darkest hour: Of course it was the Brigadier. Never has a salute been more richly earned.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.