Passion and Endurance: How Videogame Fan Translations Get Made

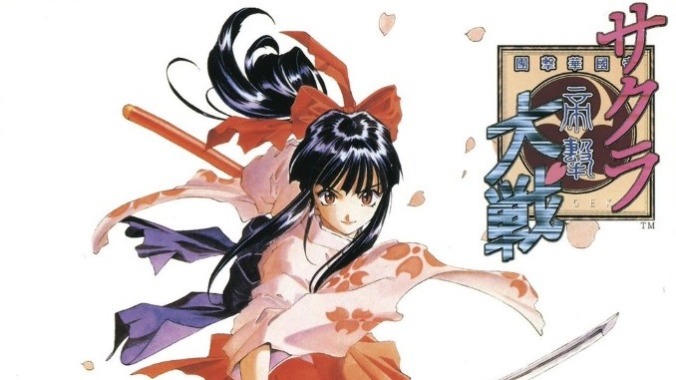

Main image: the original Sega Saturn box art for Sakura Wars

Whenever there’s a Nintendo Direct, the lead-in has some people wondering if this will finally be the Direct that announces Mother 3’s English-language release. We don’t need Mother 3, though. That’s not a referendum on the (excellent) game itself. It’s that we already have Mother 3: if you want to play it in a language besides Japanese, you can. And we can thank unofficial translators for that. Through painstaking work on their own time, these translators took the original Japanese release apart and rebuilt it for a new audience by creating a patch for the Mother 3 ROM file. As the translators themselves said, you’re on your own for finding the ROM, but the patch to make it playable in English—along with instructions for patching it—are there, and have been for 16 years now.

The patched version of Mother 3 isn’t a direct replacement for an official release, but sometimes these do-it-yourself affairs are all we’ve got. This translation work is a form of preservation that also fills in gaps in the industry’s history and our understanding of it—think of how long, for instance, it took for something as ambitious and experimental as Live A Live to be widely known outside of Japan. That title was released for the Super Famicom in 1994, but it wasn’t until a 2022 remaster that a worldwide audience got a shot at this fantastic piece of Square’s history, one described by Jackson Tyler as “the beating heart of RPGs.” The reason many of us knew this to be true before it finally got that 2022 re-release is because it also received its first completed unofficial translation way back in 2008.

“Translation” is a bit of a misnomer for what this work is. “Localization” tends to be the industry term nowadays, for reasons that make sense when you recognize what actually goes into translating these works from one language to another. As Paul Starr, a translator and editor who currently works on the weekly translated Shonen Jump manga, Me & Roboco, explained to Paste, “The practical answer is that ‘localization’ used to largely be professional jargon, a term of art that described a certain kind of translation of a certain kind of media, i.e., translations of software and games where the fact of the translation was meant to be largely invisible to the user/player. As information about how games are made has become more and more available, players have gotten more opinionated about what they do and don’t want to see in a translation, and the term ‘localization’ has become contested territory. As a linguistic descriptivist, I would define ‘localization’ as the term of art used to describe the professional field of translating software and games. It’s a specialized discipline that needs some kind of descriptor.”

That bit about “invisible to the user” is a vital part of the translation and localization experience. You’ll sometimes see calls for something to be directly translated from the original text, with the defense of this being that it maintains the original intent of the artist in question, but that obscures that things can be literally lost in translation: a joke that lands in one language, for instance, might not land in another. It might be because of what the reference is to, it might be because of some societal norm that’s not quite the same everywhere, it might even just be because what was a play on words in one language won’t present as such when translated into a different language. Something like this being left in would ensure that the translation work was not invisible, as it would be clear that something, to reuse a phrase that exists for a reason, would be lost in translation.

“When I said ‘invisible to the user,’ what I was getting at was a situation wherein the fact that the translation was performed at all is meant to be invisible,” Starr went on to say. “Consider something like the Japanese localization of the Windows operating system—clearly there’s a ton of text that has to be translated there, and thousands of tiny judgment calls that someone could potentially dispute, and they’re all ultimately in service of an experience that’s meant to make Windows feel like it was authored in Japanese to begin with.

“I think this was once typically the goal of game localization, but when your audience knows and cares about a game’s specific origin, the ‘invisible’ approach becomes undesirable. The localization needs to honor the source text, and the difficulty there lies in balancing what the creators, the translators, and the players each might consider an honorable localization.”

from the unofficial translation of Mother 3

This balance is not something new to the process of localization, either. Clyde Mandelin is a professional translator who also happens to be at the center of the unofficial translation of Mother 3. He’s the “Mato” referred to on the patch page, and, in addition to his work in the industry as a professional, has also authored books on translation. In addition to This be book bad translation, video games!, which looks at translation mistakes in videogame history, and Press Start to Translate, which studied the state of machine translation back in 2017, Mandelin has also authored multiple titles in the series Legends of Localization, which are deep dives into specific games and their localization process. The second book in this series covers Mother 3’s predecessor, EarthBound, and is over 400 pages long. That is, in part, because EarthBound has extensive dialogue that was localized from Japanese into English for its North American release: a straight translation from Japanese to English wouldn’t have worked, if the 400-plus pages of explaining the decisions made for an entire game’s worth of dialogue and text changes didn’t already alert you to that.

These localizations were enormous undertakings 30 years ago, and in this era of even lengthier and larger games, they’re no less enormous even with the more streamlined approaches to the work that now exist. Which is one of the reasons you still don’t see publishers throwing games that might not be a hit in other markets at the wall to see what’ll stick, and why some classic games, through services like Nintendo Switch Online or the ProjectEgg series, are released as-is instead of localized. Nintendo didn’t end up releasing all three of its Fire Emblem titles on the Game Boy Advance to international markets in part because their localization team was already overloaded with RPGs that would release worldwide. Some classic RPGs, first released in Japan, would take literal years before they arrived elsewhere, translated, which in turn made these hugely innovative games seem behind the time once new audiences got a look at them—part of why Dragon Quest lags behind Final Fantasy, popularity-wise, is due to early differences in the release schedules and localization work behind the two series.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.