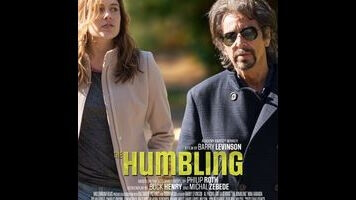

Al Pacino is the faded star of a witless Philip Roth adaptation, The Humbling

It’s through no fault of its own that The Humbling, Barry Levinson’s rambling adaptation of a recent Philip Roth novel, bears a certain passing resemblance to one of last year’s most acclaimed films. Here, again, is the seriocomic tale of an aging, washed-up actor—played by an aging, arguably washed-up actor, in a bit of art-imitating-life stunt casting—who begins to lose his grip on sanity while preparing for what could be a Broadway comeback. The accidental similarity, plain as day on paper, becomes even plainer on the screen: Minutes into the film, stage and cinema veteran Simon Axler (Al Pacino, himself a veteran of both Broadway and Hollywood) ambles out of his dressing room, the camera following close behind; gets locked out of the back entrance of the theater, and must come in through the front; and dramatically inflicts some violence upon himself before a shocked live audience. Sound familiar? Even, however, if its thunder hadn’t been immediately stolen by Birdman, which premiered three days before it at last August’s Venice International Film Festival, The Humbling would still look like a folly. Bad timing is the least of its problems.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.