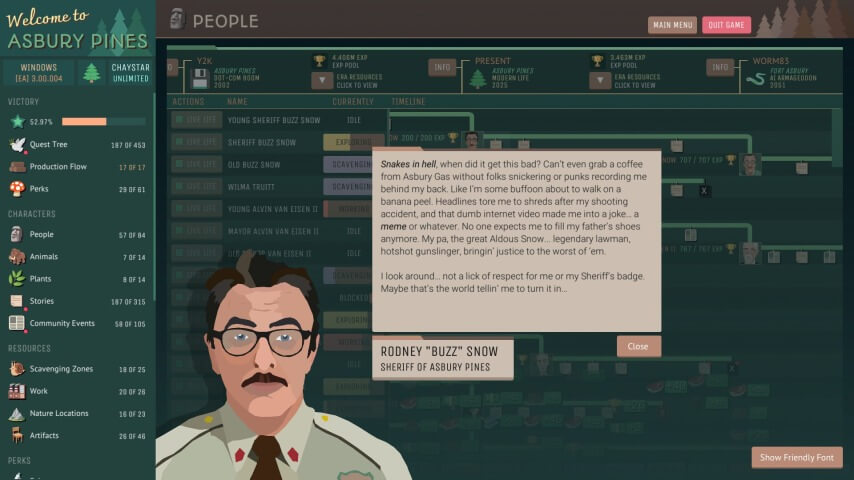

It’s into that context that a small developer called Chaystar Unlimited released a new game called Asbury Pines a couple of weeks ago. Dropped via Steam’s Early Access program, the game adopts the somehow revolutionary idea that the best reward an idle game can dole out to keep players clicking along is not a brand new set of progress bars to fill, but a new dose of well-written narrative every few minutes. In this case, these blurbs—doled out every time you score a bit of progress that usually involves burning one resource to make another, which makes another, etc.—tell an increasingly sprawling story that begins with some obvious Twin Peaks references and then spirals out, both forwards and backwards in time, to try to make some interesting points about society, empathy, cruelty, and the basic baked-in cussedness of human nature.

I’ll say, first and foremost, that I don’t love everywhere that Asbury Pines‘ narrative ultimately goes. (I take serious issue, especially, with some of the ideas set forth in its ending, which I reached after about three days of dedicated play, and which, for the sake of avoiding spoilers, I won’t go into in any more detail than, “Nah, didn’t buy it.”) But this is also a game where the journey counts quite a bit more than the destination, especially as you use various slowly accruing resources to steadily fill out the massive cast of characters (human and otherwise) that populate Asbury Pines in both its past and future incarnations. Working with limited graphics and a great (if eventually somewhat repetitive) soundtrack, the game makes dazzling moments out of contemplating the thoughts of a patch of grass, or watching a progress line suddenly veer in an unexpected direction. By linking its story to the mechanics of an idle game, Asbury Pines lets itself play complicated games with pacing and self-reference, while using its (admittedly pretty simple) game mechanics to tell stories about interdependence, scarcity, and the way one generation can make way for the next. (Or completely fuck them over, as the case may be.)

“Would it all be better simply as a book?” the strawman in my head insistently inquires. To which I can say, with some confidence, no: Chaystar is realizing here something that’s a bit like the old concept of hyperfiction—where story fragments arrive in a player-driven fashion, and at the timing dictates of both the player and the game. I don’t always like how tightly Asbury Pines bottlenecks some of this stuff to keep revelations from creeping in too early, but the charm of its narrative is of a piece with the way it delivers it: The feeling of pursuing small threads to build out understanding, then doubling back to some other tributary, is a huge part of the game’s appeal.

Sure, the game also highlights why developers generally don’t go this route: Keeping good story beats rolling out is a hell of a lot harder than creating some new tier of resources to produce, and the story focus forces the game into a decidedly finite timeframe. (Something baked into the structure of Universal Paperclips, too; it’s essentially impossible to have a satisfying story that’s also a steadily spiraling rise into numerical infinity, modern comic book publishing be damned.) But there’s real gold to be found in a game like this, where tiny snippets and short stories can sketch in human foibles in intimate and heart-rending ways, or make you feel weirdly attached to a stag beetle that briefly glimpses the infinite on the way toward its inevitable demise. Like I said, not every point the game tries to make about society, sacrifice, parenting, and more lands for me, and I certainly have my fingers crossed that its final sections will get a pre-full-release once-over for places where both the mechanics and the narrative can be polished up. But as a person who plays a lot of idle games, I can’t remember the last time one actually made me feel something, and that journey is worth noting, even if the final destination doesn’t necessarily work as the sum of all those beautifully moving parts.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.