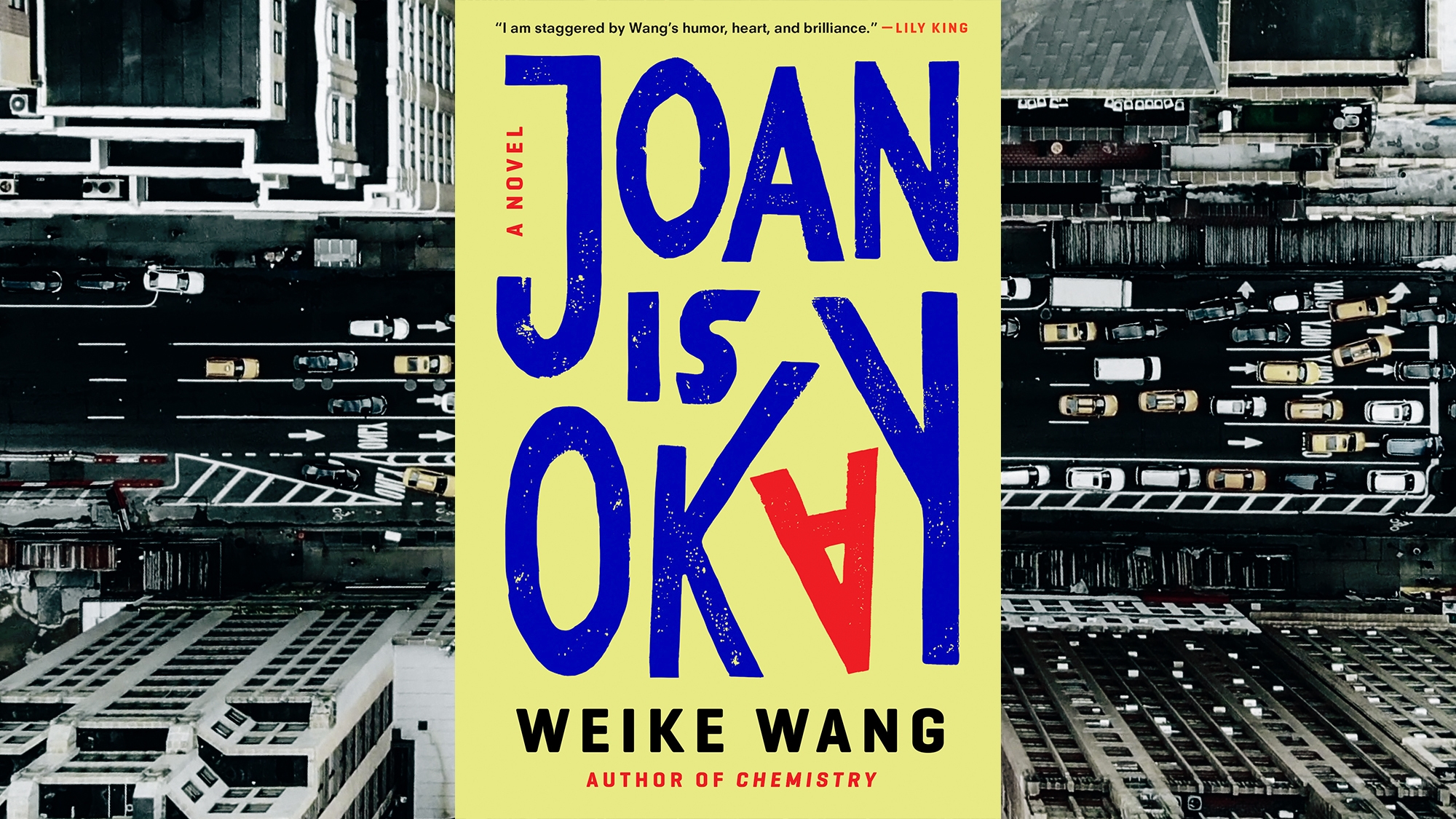

The workaholic protagonist of Weike Wang’s second novel, Joan Is Okay, can’t wait to return to her job as a physician after losing her father to a stroke. On her flight back to New York after briefly mourning with her family in China, Joan, feeling uncomfortable with the excessive amenities of first-class, exchanges her ticket for a seat in coach. A code-switching flight attendant reads her as Americanized, and assuming she only speaks English, whispers to her colleague in Shanghainese that Joan must be senseless for wanting to experience anything less than luxury. In her follow-up to her PEN/Hemingway Award-winning debut novel, Chemistry, Wang portrays the multifaceted alienation of a Chinese American woman struggling with loss.

Wang writes Joan’s exterior as cool and removed, and much of the novel’s wry humor comes from her seemingly muted emotions. In a scene in which Joan is meant to sit with her feelings, she instead matter-of-factly summarizes a Seinfeld episode to herself. Wang frequently uses such interiority to show the way her protagonist cautiously makes sense of her feelings. Throughout the novel, Joan wrestles with an all-too-familiar coping mechanism often employed by marginalized people: to appear passive. In moments of family- and work-related tension, Joan veers away from conflict by feigning acceptance, further fomenting her resentment and identity crisis.

As the narrative follows Joan from work to her apartment between Harlem and the Upper West Side—nestled among luxury condos and low-income housing—to her brother’s palatial home in Connecticut, it becomes obvious that she is not, despite the title’s insistence, okay. “Grieving was a necessary process and there were many waiting-room brochures about it,” she says. Rather than crying, Joan anthropomorphizes medical equipment. When she’s asked to take an extended leave from work, “the hospital’s way of reaching its arms out and giving [her] a hug,” she is finally forced to evaluate her detachment from her family and her identity as a successful professional, the daughter of Chinese immigrants, and an American.

Joan resists sentimentalizing the death of her father and her fractured relationship with her family. And Wang masterfully manages this emotional landscape on the page. Moments of vulnerability are crowded by Joan’s monologues on sitcoms, the medical field, the suburbs, and life support machines that, unlike people, can always be “a friend to lean on.” Epiphanies are postponed by family expectations, the general pressure to assimilate, and mansplaining colleagues and neighbors.

On the surface, these quick shifts from thoughtful reflection to seemingly arbitrary dialogue suggest Joan uses deflection to keep from grieving. Alternatively, these juxtapositions outline her private process toward healing. Early in the novel, Joan admits, “To stay just under something gives me a sense of comfort…” Rather than reverting to more familiar modes of grieving, Joan muses on “hospital-speak” and absurd expectations placed on Chinese Americans. “Someone else’s well might be another person’s not-well,” Joan’s white neighbor Mark explains, while simultaneously dictating how she should feel about the racism Asian American doctors experience at work. Mark’s lecture, while infuriating, nonetheless underscores one of Wang’s most prominent concerns in the novel: Not everyone’s grief or well-being looks the same.

When Mark throws a surprise party at Joan’s apartment without her consent, filling her space with strangers and equally unfamiliar home accessories, she meets a Korean graphic designer. The two share vocabulary from their respective languages, and later, the “postmillennial,” as Joan refers to her, says “to truly learn another language, you must listen to it through other mediums.” For the woman, watching Friends taught her a “trivial but inconsistent” English. Whether she knows it or not, Joan’s blending of medical terminology and Chinese forms her own personal language of grief. This mixing recalls a rare conversation she had with her father, in which he called Joan to speak not with his daughter but the “doctor-daughter.”

Wang is interested in language from the beginning. When Joan receives the phone call about her father’s death, her co-workers are surprised to hear her speak Chinese. In hopes of avoiding discussing her family, Joan quickly claims that although the sound she made—“chuàng”—resembles a real word, it means nothing. To herself, she admits it signifies “to begin.” In another scene, the hospital director explains phonaesthetics to her, saying that different sounds in different languages are coded with specific emotions. Joan later reminds herself that “to chuàng” also means “to create something that never was, to forge a new path.”

Author photo: Amanda Peterson

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.