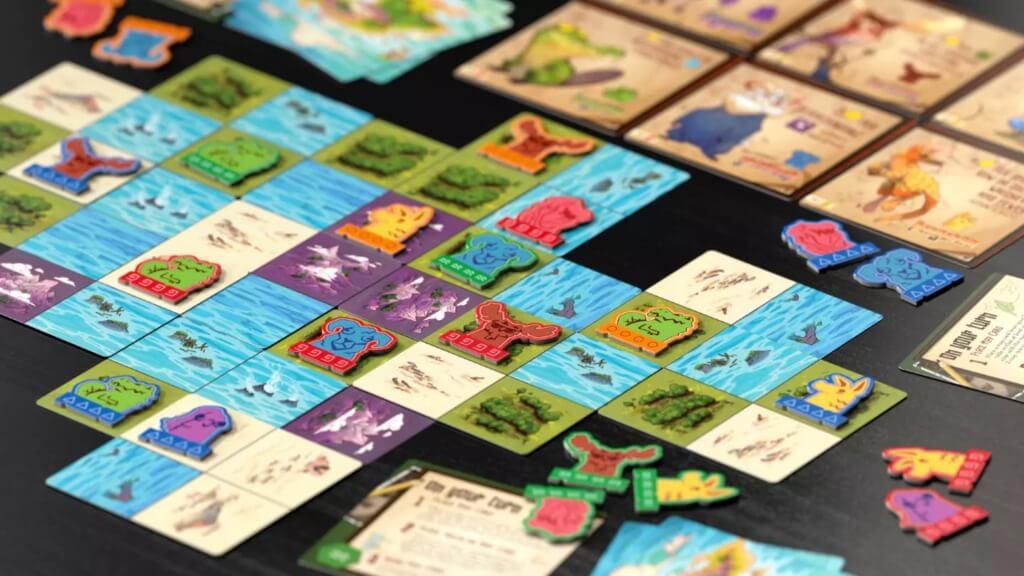

The map cards in Oddland have four squares on them showing at least two of the game’s different terrain types: water, mountains, forests, or sand. On your turn, you place one of the two map cards in your hand on to the map between all players, either adjacent to an existing card, or by “layering” it, covering one or two squares on an existing map card, a mechanic found in a number of games like Honshu and Codex Naturalis.

You’ll then place one of your animal tokens on the card you just placed. You start the game with one token for each animal type, plus one or two flora tokens, depending on the player count; thus you get only one chance to score each animal during the game. Every animal type comes with two scoring methods, one on each side of the card, so you can customize the game each time you play, although the flora tokens only score if you use the B side—if you use the A side, it’s just a throwaway turn when you place them. Most of these tokens score based on what is adjacent to, near, or in a line with the token itself, which means that almost nothing is certain in Oddland.

What makes each turn so challenging is finding the play that gives you more points, either for the new token you just placed or the ones you’ve already got on the map, and that also takes points away from one or more of your opponents. That’s also the game’s drawback; there is a lot of cognitive load in Oddland, more than just about any game of its physical size or play time I can think of. It’s like The White Castle in miniature; that game also has a limited number of turns per player, so every move has a huge weight to it. In Oddland, there’s added weight, because once you play any specific animal token, you don’t have that animal for the rest of the game. In a two- or three-player game, you get a second Flora token, so you do have a little more flexibility on that one, but otherwise every token you place has a real opportunity cost. Figuring that out, and estimating not just the points you’ll get now but setting yourself up to potentially gain more points—and/or playing defense to avoid giving your opponents a chance to screw you over—can lead to analysis paralysis. (The game’s first expansion, The Big and the Bold, adds two more animal types, each with two scoring methods, and new Flora cards to change how they score. The rules recommend choosing five animals from the seven types, but also say you can use all seven for a megagame, which might actually break my brain if I tried it.)

This all makes Oddland a game for a certain crowd or certain types of players, and not well-suited for everyone—which makes it unusual in publisher Allplay’s line, as they specialize in, as you may have guessed, games for all. It’s easy to play, but hard to play well. It’s also the sort of game that needs to find its audience; in my experience, people pick up games like this, expecting a quick or light play, while players looking for a crunchier game expect a bigger or heavier box. I wish the scoring was a little less ornate, but otherwise Oddland is a fun intellectual challenge for its price.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.