Welcome back! It’s been a while, hasn’t it? So much has changed! First there’s–er… well, the site looks a bit different, I guess. And we’ve all gotten older. But that’s the fun of TV Club Classic: we keep aging, but the classics stay the same. So, take a moment to get settled; put some popcorn in the microwave; check the couch cushions for change; and let’s dive right in.

“Genesis”

Originally aired 3/26/1989

In which Sam Beckett becomes unstuck in time…

If you’ve been on social media at any point in the past decade or so, you’ve likely seen prompts asking readers to post their favorite TV show pilots of all time. The results are fairly predictable at this point: Lost makes an appearance, as does The Sopranos, and half a dozen other prestige shows. While people don’t automatically dismiss everything made before 1999, there is an unspoken assumption that, as good as older shows can be, all of them took some time to figure themselves out.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone mention Quantum Leap’s two-part premiere, “Genesis” and I think that’s a mistake. Revisiting it now for this review, I was immediately impressed at how confident it was, and how immediately it landed on what would come to be the show’s signature tone: a bittersweet melancholy tinged with self-deprecating humor, driven by an optimism so pure it borders on profound.

A brief aside: This is not a perfect show. While it aspires to greatness, it’s from an era where TV was still not quite getting the respect it deserved, and there’s a certain lack of sophistication that you have to accept if you want to enjoy it. There are hokey bits, there are moments of well-meant but still fumbling social commentary; there are flat characterizations and unexamined assumptions; and if you were looking for a prime example of the limits of liberalism in late ’80s/early ’90s pop culture, you could do worse.

I’m not sure you could do better, though. I’m hedging here because most of my Quantum Leap memories come from my childhood. This was one of the first adult shows I fell in love with, back when I was only able to watch it in reruns, and while I’m a little nervous about revisiting it as an adult, I’m also tremendously excited to try and give the series its due. There are moments I remember (there’s a Halloween episode in here that’s an all-time favorite of mine; there’s the TV movie where Sam leaps into Lee Harvey Oswald; there’s the “evil leaper” arc, as the series desperately tried to pull in more viewers; and there is, of course, the heartbreaking finale), but there’s a lot that I don’t, and if I seem to be even more uncertain than usual, it’s because I honestly don’t know what my expectations should be.

But that’s neither here nor there: We’re talking about the two-part premiere, which is, I think, excellent. In medias res gets a lot of deserved flack these days as a gimmick, but the approach here–a brief prologue to establish something weird is going on before jumping right into Sam’s first jump–does a fantastic job of pulling us in with a mixture of mystery and almost immediate nostalgia. That last part may be a stickler for some viewers, but it’s a key part of the appeal: a kind of wistful longing translated into action. At its worst, there’s a too-easy acceptance of some of America’s self-told lies, but that acceptance is balanced by the near maniacial desire to live up to the standards of those lies. Maybe this is not who we are, or ever were… but what if we could be?

All of that is a lot to take in at once, and it would be a mistake to deny the show’s simpler, more immediate pleasures. For one, the premise is one of the best in TV history:

“Theorizing that one could time-travel within his own lifetime, Dr. Sam Beckett stepped into the Quantum Leap accelerator…and vanished. He awoke to find himself trapped in the past, facing mirror images that were not his own, and driven by an unknown force to change history for the better. His only guide on this journey is Al, an observer from his own time, who appears in the form of a hologram that only Sam can see and hear. And so Dr. Beckett finds himself leaping from life to life, striving to put right what once went wrong, and hoping each time that his next leap…will be the leap home!”

This narration, performed by Deborah S. Pratt (co-executive producer and writer for the series), plays at the beginning of nearly every episode. It is, and I will accept no argument here, perfect. You could say that it’s inelegant to spend so much time explaining the premise each week, but elegance is overrated; there’s a wonderful, reassuring directness to the speech that captures one of the fundamental pleasures of television shows in general: the routine, the familiarity mixed with the unexpected, the promise of seeing something new with old friends. And Pratt’s delivery, burned into my brain after all these years, is lovely. I particularly like the way her voice almost breaks near the end.

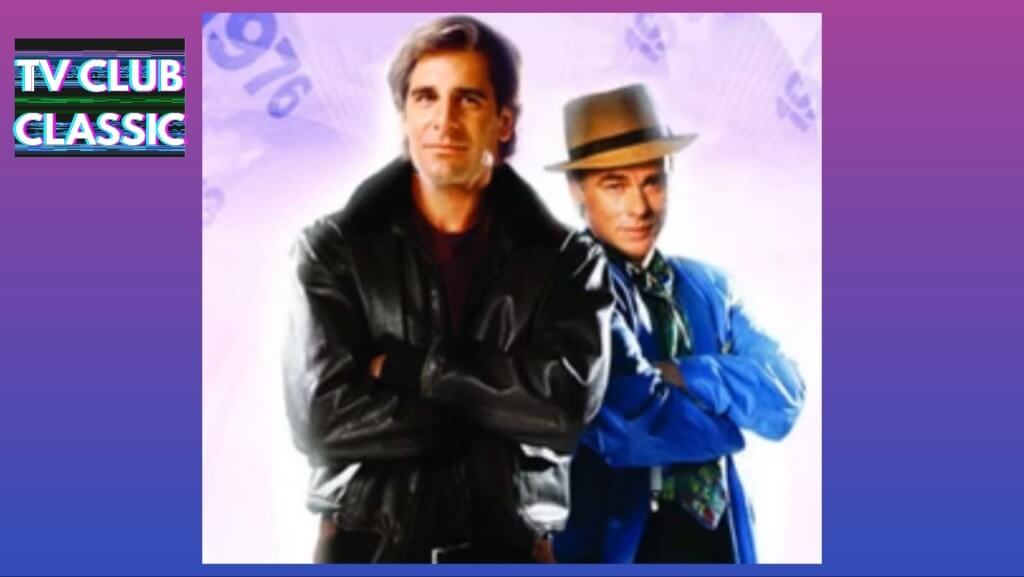

It speaks to an emotional directness that’s another hallmark of the series. As Sam Beckett, Scott Bakula (perfectly cast) is not a traditionally stoic heroic figure. He’s one of the most decent protagonists in TV history, and he’s also not ashamed of crying or admitting he’s in over his head, or connecting emotionally to the people he meets along his way. This show would not work without Bakula’s charisma and openness. In a different context, the idea of someone body snatching you at a crucial moment in your history would be terrifying. Here, it’s a fantasy, both to imagine yourself in Sam’s shoes and imagine what might happen if he ended up in yours. (As a weirdo high schooler, the possibility of getting zapped and coming back to myself to find I had a date for prom was not without its charms.)

Bakula is balanced by the show’s only other regular star, the great Dean Stockwell as Al. TV shows are as much about relationships as they are about situations, and here’s one of the best: the idealist driven to live out his idealism in the most direct way imaginable, and his snarky, world-weary buddy who just can’t help but be along for the ride. We see Al before we meet Sam, in one of the show’s rare glimpses into the future; it’s an odd, stiff sequence that has Stockwell hitting on a not-at-all displeased young woman before all hell breaks loose. They were clearly working on a budget, but I appreciate how impressionistic everything is—a tomorrow full of empty landscapes and mysterious science, and, oh yeah, horn-dogs.

If I remember right, the show’s approach to sexual politics (much like its approach to racial politics, and politics in general) is “well-meaning but dated”; I’m going to reserve judgment for now, and just remark that we quickly get to know Al’s two defining characteristics, his wild fashion sense and his endless womanizing. The latter is played largely for laughs, and I’ll go out on a limb to say that Stockwell manages to make it more charming than predatory—we’ll learn later there’s some backstory behind his bed-jumping, but for the most part, he comes across as a guy who enjoys women, enjoys having fun, and doesn’t make anyone suffer inordinately for either quality.

So, we’ve got Sam, and we’ve got Al, and we’ve got our premise. As every good pilot should do, “Genesis” puts those pieces to work and gives us a rough idea of how the series will work going forward. In this case, our hero has traveled to 1956 and taken the place of Tom Holton, a married test pilot on a team pushing the limits of an experimental military plane. As he gets to know Tom’s wife, the very-pregnant Peggy, and the other men in his squad, Sam struggles to remember who the hell he is, why he doesn’t recognize himself in the mirror, and what on earth he needs to do in order to get back to his own body.

That last part is the hook that keeps the show moving. Quantum Leap belongs in “wandering hero” genre made famous by shows like The Fugitive, and like all those shows, there’s an instigating circumstance (in Sam’s case, his decision to say fuck it and jump into the accelerator, come what may) and there’s an ultimate goal that may or may not be reached. But what makes it such great grist for television is how the ultimate goal is actually made up of a bunch of smaller, more attainable goals, a problem that can be solved each week before the credits roll.

On Leap, the trick is always as much about finding out what that problem is as it is about figuring out the answer. Ziggy (the computer Sam programmed to run the project, and the good, fictional version of AI) will suggest theories that Al will propose to Sam, and Sam will do his best to achieve them. Sometimes, as in “Genesis,” those theories will be wrong: Sam survives a flight that killed Tom, but it turns out what actually matters is Peggy and her baby. With some quick thinking (and remembering his own extensive future medical training), Sam is able to stop Peggy from going into premature labor, saving her and the baby, and allowing Sam to leap into his next subject.

There is, of course, an assumption built into this: Someone is controlling these leaps, and someone has a purpose. Those new to the series should be aware: This is not a mystery show, à la Lost (I love Lost), and while there are attempts to provide more lore in later seasons, those attempts are often misguided and silly. All you ever really need to know is in that opening speech: “trying to put right what once went wrong.”

Time travel stories can be about a lot of things, but this one is about embracing a fantasy where the smartest man in the world has given his life to try and make the world a better place for everyone, one person at a time. It’s about getting a second chance, or maybe even a third or fourth. We’re not worried about paradoxes, for once. We’re just fixing the mistakes, one broken heart at a time.

Stray observations:

- I’ll have more to say about individual episodes going forward; the most notable point to make about “Genesis” is how slow moving it is, and how it allows Sam, and the audience, to settle into the situation by degrees. I’m sure I’ll be saying this often, but Bakula really is perfectly cast. He’s handsome, so you never feel that weird about ladies wanting to make out with him (even if they can’t see his actual face), he’s emotionally available, and he’s eager to please, a golden retriever in human form.

- “Genesis” also features an extreme rarity, a second in-episode jump; once Sam saves Peggy, he ends up in a baseball player in the minor leagues, stealing a home run to save his team from a losing season. (The stakes change a lot from week to week.) It’s a slight sequence, mostly here to give Sam a chance to call his dad. Sam’s relationship with his father will get referenced again, and your tolerance for their phone call should give you an idea of how you’ll handle the show’s unabashed sentimentality going forward. It got to me, at least.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.