However the play began, it can’t have been in the same striking way that the movie opens: with a man plunging into a swimming pool, fully dressed, then emerging with his face shrouded in a stocking mask. This turns out to be an escape from a robbery gone wrong (never otherwise seen), in which Kenny (Kevin Janssens) gets left behind, for reasons left unexplained, and winds up doing four years in prison. While he’s inside, his brother, Dave (Perceval), goes straight, taking a job at a local car wash; his junkie girlfriend, Sylvie (Veerle Baetens), gets clean; and Dave and Sylvie become romantically involved, without telling Kenny that they’re together. When Kenny unexpectedly gets paroled, Dave, who still feels guilty that his brother took the fall for all three of them, can’t bring himself to reveal the truth (including Sylvie’s pregnancy), inventing a fake girlfriend named Julie. Unfortunately, this only encourages Kenny to court Sylvie anew, even though she stopped visiting him in prison two years earlier. She ignores his calls. He crashes one of her recovery meetings and harasses her. Things get much, much uglier from there.

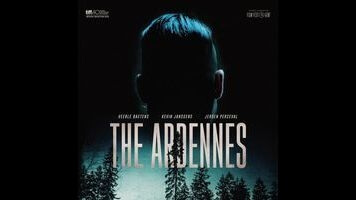

Part of the problem with The Ardennes is that it’s built around what Roger Ebert used to call an “idiot plot”: Had Dave just told Kenny, while Kenny was safely incarcerated, that he and Sylvie had fallen in love, it would have given his brother a couple of years to cool off. Waiting until he’s released and then trying to pretend it’s not happening, using the patented Jan Brady “George Glass” method, is not recommended. Mostly, though, the film is just undistinguished, both visually and dramatically. Pront, after that disorienting initial salvo, leans hard on photogenic locations (both beautiful and ugly), but doesn’t come up with compositions that are worthy of them. And Perceval, who’s previously appeared in Bullhead and Borgman, is a much stronger actor than writer, at least on the basis of this work. One potentially tense sequence, involving a game warden snooping around a car with a corpse in the trunk, would have been much more effective had it not been preceded by a brief scene of the game warden kissing his wife goodbye, which clearly has no function except to mark the guy as dead meat. When someone gets killed by the Dardennes—see Lorna’s Silence, for example—you never see it coming.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.