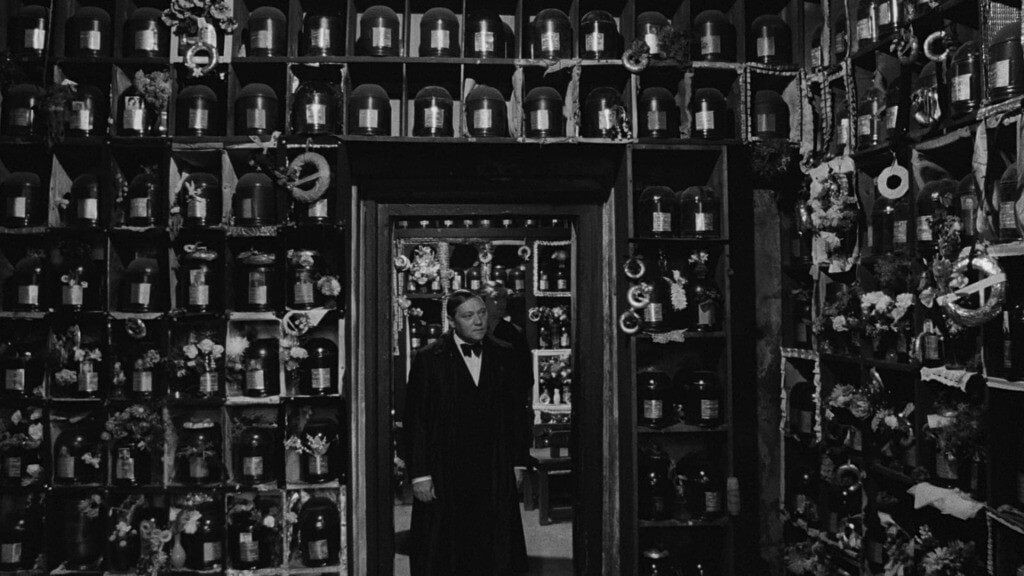

But sequestered away alongside the progressive politics was Herz’s blisteringly singular aesthetic, defined by Terry Gilliam-like cutout animation, kinetic modern editing, fisheye lenses that’d make Yorgos Lanthimos queasy, and an all-timer weirdo performance by Rudolf Hrušínský. Hrušínský plays Karel Kopfrkingl, the sweaty and beady-eyed ascetic who acts as the personification of the fascist death drive. Not only does he run a crematorium, wheeling coffins into the flames and collecting the ashes, he personally invests in a pseudo-Buddhism where death becomes a kindness for suffering souls—they’ll just be reincarnated once freed from their fleshy prisons, after all. Like it is for so many strange movie killers, death is a blessing, and administering it is an act of care. Karel smooths his corpses’ hair with his own pocket comb, and obsesses over the details of funereal ritual. In this way, The Cremator has another tie to a 2026 horror film: Karel refers to his mortuary as his “temple of death,” echoing the macabre and reverent proprietor of The Bone Temple.

Herz’s filmmaking is anything but reverent, however. This is no Zone Of Interest, where banal evil becomes static, suppressed—even picturesque. The Cremator is a manic film, lodged deep in an unstable psyche. It’s full of explosive cuts and expressionistic montages, not to mention its Peep Show-like POV distortions and constant tonal usurpations (nude women are juxtaposed with hunting imagery; scenes transition with comically misdirected match-cuts). At one point the camera rides down the catafalque with a body, positioning the audience itself atop the centerpiece of death. It’s a riveting and upsetting aesthetic, constructed through cinematographer Stanislav Milota’s grab bag of tricks, and one that effectively steers the horror film away from dread and towards no-brakes terror.

As Karel and his performative abstinence (he doesn’t smoke, or drink, or sleep around, except when he does) are bullied by the Nazism encroaching upon his country, his mental state becomes even less predictable, and even more apt to contort its principles to fit into the powerful nearing ideology. He’s not merely a collaborator, but a small man eager to warp his values in order to conform. His hypocrisy becomes more blatant, his distaste for “weakness” and the “effeminate” more pronounced, his imposing girth more threatening. By the film’s end, he’s fully merged his beliefs into a single fatalistic outlook, shouted from a Riefenstahlian pulpit: “The Führer’s happy new Europe and death. These are the only two certainties we have as human beings.” This does not bode well for those around Karel who haven’t yet accepted Nazism into their hearts, whether they’re employees or family members.

Unseen troops close in around the country’s borders and the specter of death closes in around Karel, coming to a head in a hallucinatory climax where a monk-robed version of Karel declares himself the next Dalai Lama. It’s a gallows-humor gag about all the outlandish lies and logical gymnastics required for people like Karel to justify their cruelty, a self-deluding streak persisting in modern-day totalitarians. And Herz never puts his faith in subtlety: Karel’s holy doppelganger turns up around the same time as the newly anointed Nazi giddily accepts the role of gas-chamber commissar while standing in front of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden Of Earthly Delights. There’s certainly something otherworldly happening here, but it’s a grotesque vision of hell rather than the blissful release of nirvana.

The cowardice and capitulation in The Cremator offer something far more disturbing than the literal ghouls in The Mortuary Assistant. It’s a film that, more than simply frightening, possesses a pervasive sense of evil. Perhaps this is because death is not the film’s most disturbing consequence, or most unsettling threat. Rather, The Cremator fears the weakness that serves as the foundation of so many of history’s greatest evils: A weakness that would rather kill what it loves than put forth effort in order to protect it, a weakness so certain of failure that it preemptively surrenders to it.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.