With Together Again, Jesse Hassenger looks at actors and directors who have worked together on at least three films, analyzing the nature of their collaborations.

Mark Wahlberg could have prevented 9/11. That’s not exactly what he said to Men’s Journal back in 2012, but it was close enough to warrant a sort-of apology days later. It was also an expression of actorly hubris memorable enough to outlive some of his movies: In certain circles, the image of the erstwhile Marky Mark personally rewriting history and sparing thousands of innocent lives may be better-remembered than Contraband, the project he was promoting at the time.

One reason Wahlberg’s comments have enjoyed such a shelf life is the movies that followed them. About two years after imagining a new 9/11 starring himself, Wahlberg did the next best thing, playing a real-life Navy SEAL who survives a brutal Taliban attack in Afghanistan. Apparently, he got a taste for both the role-playing and the director involved; Lone Survivor was the first of his five collaborations with Peter Berg, including two more movies that rip their stories from the headlines, then paste Mark Wahlberg smack in the middle of them. If this feels like Wahlberg fulfilling his fantasy life as a genuine man of action, it seems to give actor-turned-director Berg even more of a calling: His five movies with Wahlberg are also the five most recent feature films on his CV. This is what he does now.

It’s easy to see why Berg and Wahlberg (WahlBerg for short) might get along. Wahlberg made the tricky transition from rapper to model to actor, while Berg successfully moved from acting to directing. Both men take something of a journeyman approach to their profession: Wahlberg can do serious work for Martin Scorsese or Paul Thomas Anderson, meat-and-potatoes action programmers, or self-parodying comedy with Will Ferrell or a teddy bear, while Berg has directed a sports drama, an old-fashioned action buddy comedy, and a weird superhero fantasy, among others. Yet they both seem aware of their limitations, too (The Happening notwithstanding); they’re mutually unlikely to, say, make a musical, or tackle a sword-and-sandals epic.

Although Wahlberg has appeared in far more movies than Berg has directed, it’s his star power that draws the boundaries in their work together. Most Wahlberg movies are at least partially about his particular strain of masculinity: a form of old-school stoic sensitivity that feels paradoxically contemporary, at least in the sense that it’s difficult to picture Wahlberg in a period piece that goes further back than Boogie Nights. That breakout movie for both Wahlberg and writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson established a template for several of the actor’s notable early roles. In projects as disparate as Boogie Nights, The Big Hit, and Three Kings, Wahlberg embodies various stereotypically masculine ideals as he betrays a surprising sweetness. These characters match his signature actorly tic: the way his voice often moves from a Southie mumble to someplace higher and lighter. He doesn’t have the widest range, but that change in tone, adorned with invisible question marks, can mean anything from genuine concern to baffled incredulity to macho sarcasm. He can embody alpha-male aggression, as with his Oscar-nominated turn in The Departed, or parody it, as in The Other Guys.

His movies for Berg fall closer to his Departed work, only without the lacerating humor. It’s not that unchecked male ego runs wild through WahlBerg’s movies—especially not their trilogy of reality-based dramas. Lone Survivor, by virtue of its last-man-standing structure, comes closest to refashioning a true story into a star vehicle. Deepwater Horizon (about the BP rig explosion that led to the biggest oil spill in history) and Patriots Day (about the Boston Marathon bombing and the ensuing manhunt) have muscular ensemble casts and vaguely procedural approaches that allow for plenty of scenes without Wahlberg in them at all. In all three movies, he plays a seasoned professional, usually with some form of loving family, who finds himself in extraordinary circumstances.

At the same time, plugging Wahlberg into these roles, especially after nearly two decades of big-screen stardom, creates some unavoidable distractions. To some degree or another, all of these movies re-orient themselves around Wahlberg’s heroics. This is most galling in Patriots Day, where the process of constructing his composite character turns him into a plainspoken hero cop with a mental map of Boylston Street and an innate understanding of how the good people of Boston will lead law enforcement straight to the suspects if they release their photos to the press. Deepwater Horizon doesn’t lean on him as heavily, but he’s still the guy who keeps his cool and tells everyone to calm down when they need to hear it most; the movie climaxes with him saving the life of his coworker (Gina Rodriguez) through sheer force of will. Perhaps more importantly, if there’s a menacing noise in the distance, the movie cuts to a close-up of Wahlberg’s face, checking in with his reaction.

Given Wahlberg’s offscreen persona, it’s easy to read these movies as a deluded self-image about how he would act in a crisis. At the same time, they aren’t individually bad performances (though none of them are among his most interesting either). It’s only together that they start to resemble a fixation, because Berg either teases out his star’s sense of righteousness or combines it with his own. Lone Survivor in particular fails more because of Berg than his star. It’s the kind of quasi-apolitical narrative that concludes the best way to support the troops is to gawp at the physical sacrifice involved in them getting gorily killed. As the follow-up to Berg’s failed Transformers knockoff, Battleship, it weirdly anticipates Michael Bay’s Benghazi action-drama 13 Hours: a movie where a profoundly unserious thinker decides he can both contribute a living history and play it super-loud for the cheap seats.

All of Berg’s true-life adventures have that queasy cobbling together of a faux-documentary aesthetic (lots of handheld cameras and following shots) with sweet pyro. He can’t resist staging a horrific shootout between a bombing suspect and a bunch of cops as a quip-heavy set piece in Patriots Day. That movie and especially Deepwater Horizon also have the saving grace of Berg stumbling toward later-period Clint Eastwood territory; Deepwater is especially compelling as a procedural about professionals muddling through tragic circumstances created by the fools in charge. Viewed in close proximity, it becomes clear that this trilogy doesn’t turn real tragedies into Mark Wahlberg action movies, at least not all the way. If anything, Berg falters by trying to turn his macho heartthrob into a Tom Hanks figure.

Wahlberg has been vulnerable in plenty of movies—it’s at the heart of most of his best work, with the exception of The Departed. So it makes sense that Berg would want to use that vulnerability for his weighty dramatic thrillers. In Deepwater Horizon, Wahlberg’s beleaguered electronics technician makes it through a gauntlet of fire and destruction to wind up dazed and embracing his family back on land, tearfully grateful he survived. In Patriots Day, there are even more moments of vulnerability, including an early scene where a knee injury makes it painful for his cop character to bust down a door, and a mid-movie breakdown over the horrible things he witnessed at the bombing site. Crucially, Berg doesn’t fully trust these scenes to convey the lingering terror at hand; he passes real-life events to Wahlberg for movie-star dramatization, and then hands the stories back to the real-life participants with extended documentary-style postscripts and interview footage. His star gets caught in the middle, playing underwritten and emotionally load-bearing characters. (Wahlberg is a good actor, but is he the guy to deliver a monologue about the healing power of love, as he does in Patriots Day?).

Although the WahlBerg docudramas are muddled, they at least start from the terra firma of actual events. Their two most recent collaborations attempt to leave true-life adventures behind (at least until Wahlberg talks his buddy into restaging 9/11, or maybe some phase of the COVID-19 pandemic). The results are bafflingly lousy. Mile 22 and the recent Netflix production Spenser Confidential aren’t just airport-novel time killers beneath the talents of those involved. They’re franchise-starters so listlessly overplotted that they come across like failed TV pilots. They also feel emboldened to let Wahlberg caricature himself, as if crying on screen in a couple of re-enactments earns him the goodwill to act like a raging dickhead for fun.

If Berg’s faux-documentary instincts steered Wahlberg toward a more grounded version of action-movie heroics, Wahlberg is now steering Berg into generic star vehicles, justified as the fun they get to have after proving they’re good, thoughtful people deep down. The weird thing about this is that Berg has made good star vehicles before: The Rundown, while not a huge hit, helped break Dwayne Johnson into movies, and Hancock is one of Will Smith’s more adventurous projects from his run as the biggest star in the world. Mile 22 and Spenser Confidential are both movies that, had they arrived earlier in Wahlberg’s career, might have actually acted as stardom inhibitors.

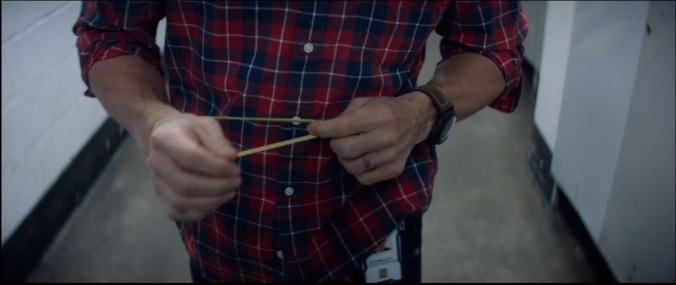

Wahlberg should be easy to miscast, so it’s impressive that it only happens occasionally. With Mile 22, Berg ups the ante from The Happening (where at least Wahlberg might get by as a particularly outmatched high school science teacher) by making his character an actual genius, a CIA officer who’s always the smartest guy in the room, which he proves by snapping rubber bands and yelling (you know, like a genius). Spenser Confidential doesn’t push that angle so hard. Instead, it confers upon Wahlberg a near-invincibility that famous actors seem to mysteriously acquire on screen around middle age. And despite Wahlberg’s fondness for fistfights and shootouts, he’s not an especially interesting physical presence in action movies. For Berg’s part, he seems more than willing to forget his past facsimile of Bruckheimer-era slickness and embrace the indifference of third-tier Netflix productions.

None of these WahlBerg productions are the worst movie Berg has ever made, and it’s doubtful any of their future collaborations will be either, because his feature debut was the vile, sweaty, self-satisfied Very Bad Things. That movie is so eager to reveal the heart of darkness beating beneath upper-middle-class professionals that Berg’s later affinity for Wahlberg characters and their barely-concealed hearts of gold could be read as penance. The idea seems like it would appeal to Wahlberg, too; he clearly wants to believe in himself as a tough-yet-sensitive family man, a little rough around the edges but in possession of a strong moral compass. Maybe this helps him square the discipline of his current family life (and workout routine) with a violent past that includes racist assaults.

Or maybe he just likes imagining what he might do in an extreme situation, something he probably shares with a lot of actors who haven’t specifically discussed how they might have stopped 9/11. Setting aside psychological speculation, there’s something mutually limiting about this partnership. One of Wahlberg’s other frequent collaborators is David O. Russell, who often throws his actors into chaos, and Berg’s earlier movies genre-hop with confidence. Together, these two have found stability as they box each other in. WahlBerg isn’t just a portmanteau; it’s also a middling brand.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.