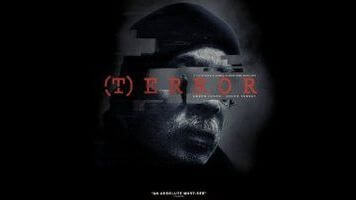

For the first half of (T)error, it feels like Lyric R. Cabral and David Felix Sutcliffe are getting away with something. A decade ago, Cabral befriended a man named Saeed Torres, a Muslim who confided in her that he occasionally works as an undercover informant for the FBI, cozying up to persons of interest and gathering intelligence about possible terrorist activity. At the start of the documentary, Saeed takes a new assignment in Pittsburgh that he intends to be his last, and allows Cabral and Sutcliffe to tag along, letting them film his classified documents and his text messages—both with the agency and with his target. Neither the filmmakers nor Saeed has gotten permission from the FBI to do any of this.

But as the story plays out, the cheap thrill of peeking behind the curtain turns into creeping dread, and then outrage. Saeed is no master spy. He’s a cranky, paranoid, pot-smoking former Black Panther, who got in trouble with the law when he was younger and ever since has stayed out of prison by letting himself be the FBI’s eyes and ears on the ground for operations that border on entrapment. His latest POI comes across in (T)error as more obnoxious than dangerous. Khalifah Al-Akili is an American-born Muslim convert and conspiracy theorist, whose biggest threat to the government so far amounts to a series of pro-Taliban Facebook posts. As Saeed—using the name “Shariff”—tries to coerce Khalifah into saying that he’s interested in going to an actual terrorist camp, even the informant begins to question whether this mission is worth anyone’s time.

Because of the nature of (T)error, Cabral and Sutcliffe were limited in who they could talk to—or at least who’d be willing to go on the record. As a result, the movie feels like it should come with a series of footnotes and disclaimers, delving more into the people Saeed/Shariff has helped put away over the years, and hearing multiple perspectives on whether these kinds of cases are necessary. (T)error’s limited focus makes it effective as a jittery cloak-and-dagger thriller, but curtails its use as a thoroughly reported piece of journalism—or even as a call to action.

But there’s nothing wrong with using the basic form of a documentary to make a you-are-there film, featuring a fascinating and morally complex character—or even to use the circumstances of that man’s life to argue that the war on terror has devolved into a series of paltry skirmishes. (T)error moves forward chronologically, and features enough astonishing twists to rival any episode of Homeland. But it’s also a pointed corrective to the lurid depiction of terror cells and covert investigations in Hollywood movies and TV shows. Cabral and Sutcliffe let their cameras linger over Saeed’s Dunkin’ Donuts muffin wrapper, and Khalifah’s stack of PS3 games; and they spend a lot of time watching their subject squabble with his superiors over getting paid. There’s no cavernous strategy room with charts and monitors in (T)error. There’s just one guy hanging around Pittsburgh mosques, trying to dredge up enough damning-sounding evidence to justify another paycheck.