I’m a year-round listener of “Auld Lang Syne,” the Scottish folk song about distanced friends catching up over a few pints, so the countdown to the new year is my time to shine. When the clocks strike midnight on Wednesday, I hope millions more will also be belting this New Year’s Eve anthem at the top of our lungs, from beginning to end (or at least the pieces you can remember and/or pronounce). But I also need everyone to know that Robert Burns, the Scottish bard who “wrote” it…kind of sucked.

The 230-year-old song—which was first a centuries-old poem—obviously has a long and rich history, including a big moment in the first Sex and the City movie and inspiring a popular suffragette song about men who don’t believe in women’s rights. So I’m not suggesting we cancel a dead man or shut off “Auld Lang Syne” for the rest of time. But it’s important to know where our great works of art come from (take notes, Chappell Roan). In 2018, Scottish poet and playwright Liz Lochhead called Burns the Weinstein of his time, so let’s brought this to mind, shall we?

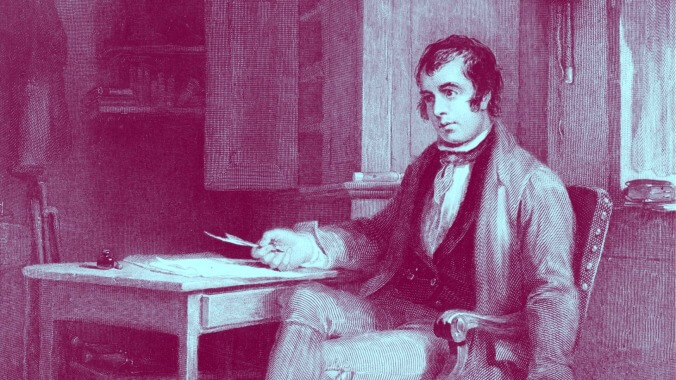

Burns was an 18th-century Scottish poet and lyricist known for writing humorous, clever poems. His most famous works included “To a Mouse,” a poem he allegedly wrote after accidentally plowing down a mouse’s home in his childhood farm, which also inspired Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men; “Address to a Haggis,” a literal ode to black pudding; and “Selkirk Grace,” a short pre-meal prayer about gratitude and food. His work also inspired many historical (and modern) greats, such as JD Salinger, Bob Dylan, and Abraham Lincoln. But perhaps most famously, Burns is credited with putting “Auld Lang Syne” to paper.

In a single-review episode of his podcast, The Anthropocene Reviewed, John Green gave the song a five-star rating, saying “it’s the rare song that is genuinely wistful—it acknowledges human longing without romanticizing it, and it captures how each new year is a product of all the old ones.” The poem, which translates from the Scots language to “old long since,” had been shared in Scotland as early as the 16th century. And while it’s typically used for graduations, good-bye parties, and New Year’s Eve, it’s also perfect for plunging yourself into a reflective, nostalgic state of mind while wandering through the grocery store on a dreary Thursday afternoon when you’re in the mood to tear up, but not cry… or at least, that’s what I’ve heard.

But while Burns is beloved by many—having written more than 500 poems and getting a dedicated “Burns Night” in January in Scotland and across the Scottish diaspora, where people gather to share his poems, eat haggis, neeps (rutabaga), and tatties (potatoes), and drink scotch—he’s lesser known for being a womanizer and a cheater.

Burns’ character came under particular scrutiny in 2018, after Lochhead gave a talk on “Burns and Women” at the height of the #MeToo movement. She highlighted a letter Burns wrote to his friend in 1788 about his then-pregnant girlfriend, in which he fantasized about giving her a “thundering scalade that [would electrify] the very marrow of her bones” on a floor covered with horse shit. He added: “I have fucked her till she rejoiced with joy unspeakable and full of glory.” Huge yikes.

“[It’s a] disgraceful sexual boast [that] seemed like a rape of his heavily pregnant girlfriend,” Lochhead said. And to her point, “scalades” are military assaults where soldiers use ladders to breach walls and infiltrate bases—ergo, not the most pro-consent choice of words. “It’s very, very Weinsteinian,” she continued. “[Burns] was a genuine romantic, easily flamed to passionate love. He was a sex pest as well I think.”

Based on Burns’ poetry alone, it’s easy to assume he didn’t respect women and made a habit of diminishing them. In one work, he asserted “Nine inch will please a lady” (hm); in a letter, he wrote to a woman, “What ails ye now, ye lousie bitch” (yikes again); and in a poem, he lamented about the lack of one woman’s pubic hair: “To think that I had wad a wife, Whase cunt was out o’ fashion” (I mean, we could do with more of this pro-bush attitude, but not like this).

In 2022, four female poets (dubbed the Trysting Thorns) were commissioned by the Scottish National Library to identify “creative responses by women to the life and work” of Burns, and all of them called for the bard to be recognized as a misogynist. Speaking about his legacy, they compared his behavior to the bros of today. “Here we are in the 21st century and women are still experiencing misogynistic responses from some men who feel they are entitled to their affections.” They also addressed how hard it is to separate the man from the poetry.

Luckily, separating Burns from “Auld Lang Syne,” at the very least, is an easy task. It was created long before him, and his one contribution—the original melody—is rarely used anymore. More common now is the tune popularized by Guy Lombardo and His Royal Canadians in 1951. But if you prefer Burns’ original tune, you can always refer to the SATC version.

Plus, the melody was used by suffragettes in the 19th century to sing “Keep Women in Her Sphere,” a cheeky song written by Elizabeth Knight, a doctor and campaigner for women’s suffrage who was once thrown in jail for asking the Prime Minister why he “promised manhood suffrage in answer to a demand for votes for women.” Knight wrote a number of songs, but this one laments the men who want women to stay in their domestic place and praises one single man who thinks a woman should “choose her sphere.” That’s as good a legacy as any.

So, this New Year’s Eve, whether you’re watching fireworks, uploading a nostalgic slideshow on Instagram, or getting ready to stream Zohran Mamdani’s mayoral inauguration inside an abandoned New York City subway station on January 1, I hope you’ll take a moment to tak a cup o’ kindness yet, for auld lang syne. And may Robert Burns be forgot and never brought to mind.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.