The Smashing Machine will be most people’s introduction to Mark Kerr, the soft-spoken mixed martial artist who was brawling back when the Ultimate Fighting Championship wasn’t yet a toxic cultural juggernaut, just lurid pay-per-view “human cockfighting,” in the words of John McCain. But the film that Benny Safdie and his star Dwayne Johnson have effectively remade—often shot for shot—is better in every way than the dramatized biopic born from its bruises.

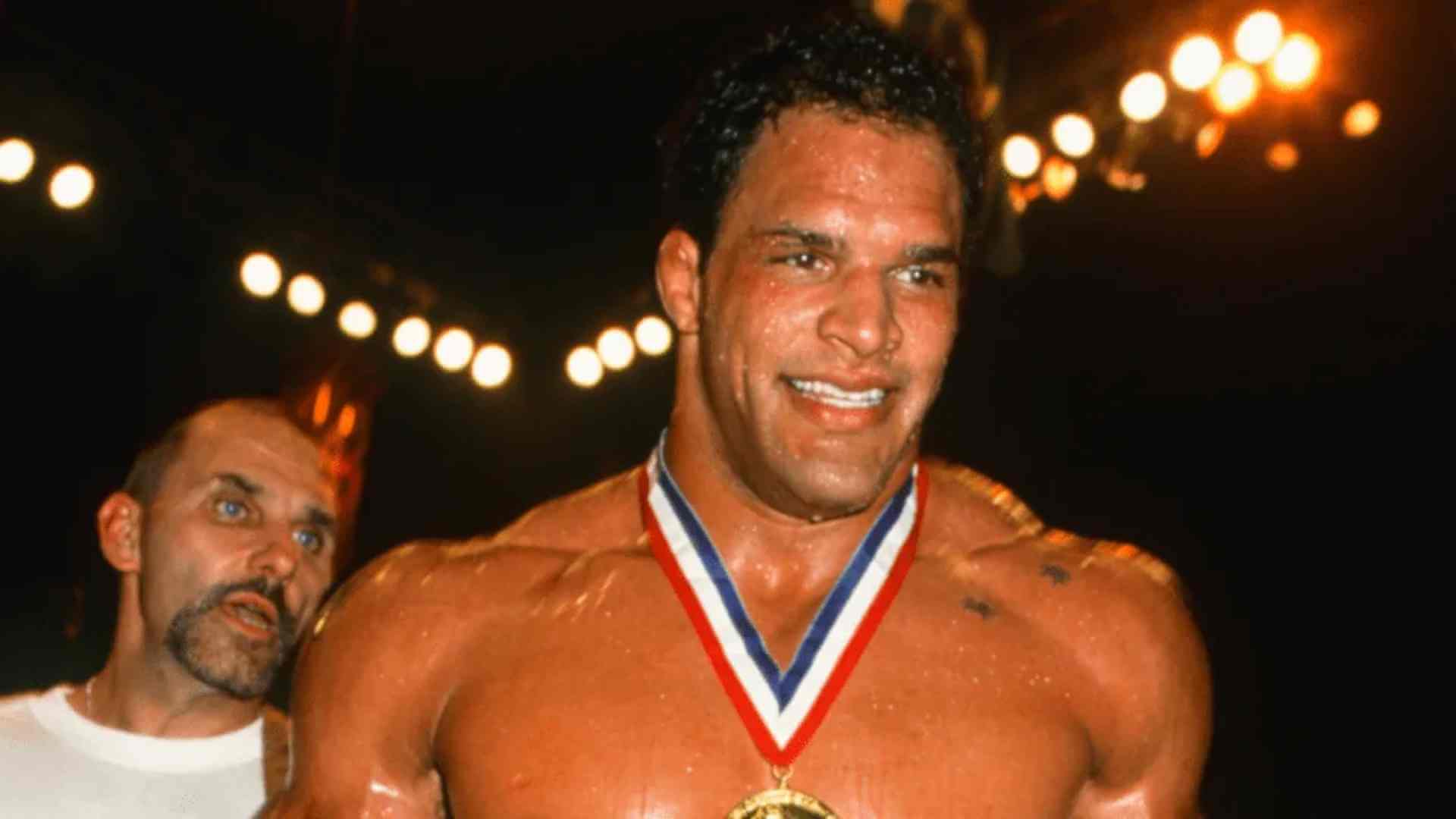

John Hyams’ 2002 HBO documentary The Smashing Machine: The Life And Times Of Extreme Fighter Mark Kerr lets its subject’s aw-shucks personality and the wet, meaty thwack of knee strikes and hammer fists speak for themselves. This lends subtlety to a fall-and-rise arc that could otherwise knock you in the face with its grimdark spin on a pro wrestling narrative. Ambition and acceptance, violence and tenderness, life-affirming pain and the life-threatening drugs that assuage it—these archetypal dualities all reveal themselves naturally during the fly-on-the-wall, backseat observations of a normal man’s abnormal job. Kerr’s soft voice, little-kid smile, and gentle patience (even when, in simplified English, he’s arguing over money with the Japanese middlemen of the Pride Fighting Championships) breezily define The Life And Times‘ contrast between person and profession.

Like Kerr tells an older lady in a doctor’s waiting room, he doesn’t hate his opponents. Not at all. The idea is almost laughable to him. It’s just a job, and they’re just his coworkers. It’s one of countless moments meticulously reconstructed in The Smashing Machine, replicating the words without the spirit (a little like the clunkier moments of The Room biopic The Disaster Artist). When Kerr has this conversation, it sounds like he’s had it a million times, with his parents, with folks in the checkout line, with people on the bus. A familiar refrain trotted out at cocktail parties. The Rock can’t help but sound coached, like he’s talking down to someone on a red carpet, even when repeating the footage verbatim.

That’s one side of Mark Kerr, one side of The Smashing Machine. Then, when the shirts come off and the lights go up, Hyams captures the combat with a similar inimitable clarity. Just as The Life And Times hovers in the corners of Kerr’s suburban Southwest life—the perfect vantage to see all the ugly and strange little details poking out of the Americana, like hypodermic needles out of a black Hefty bag—Hyams keeps his camera unflinchingly locked on the thudding collisions between elbows and ribs, knees and skulls, fists and livers. Safdie’s film is enamored of the spectacle, of the life-defining gulf between winning and losing. His fights cut away to crowd reactions, overwhelmed by the lights and music. Hyams stares blankly at the bloody damage, scored mainly by the dull sounds of human meat being tenderized.

This could be linked to the movies’ respective relationships to the MMA of their eras. Hyams made his film when the sport was still on the relative fringes, its brutality banned across the U.S. and its reputation, as the woman in the doctor’s office reminds us, still obscene. The Smashing Machine is set in this era, but was filmed with the knowledge that the sport would rise again, boosted to respectability by an increasingly toxic TV environment (Spike TV was UFC’s savior) and the always alluring promise of cash. Colored by this future, The Smashing Machine broadens its approach to the wider audience MMA now commands. Hyams’ documentary was entrenched in the grungy, strange, relatively underground indignities of Kerr’s career—it simply didn’t know any other way to be.

This difference is captured, unassumingly, by a small deviation The Smashing Machine makes from The Life And Times. At the end of The Smashing Machine, when a fight is inter-cut with Kerr getting his chin stitched up in a side room, the doctor attending to him is American, chatting with him nonchalantly in English. In reality, because this tournament was held in Japan, the doctors sewing him up were Japanese, and were speaking to each other in a language Kerr couldn’t understand. The latter scene, the real scene, doesn’t just juxtapose a competition Kerr has been knocked out of with the toll taken on his body. It spotlights a man who, when outside the ring, is alone and isolated, lost among people who know what to do with his body, but not with him.

These silent insights are also found in what the documentary doesn’t show of Kerr’s relationships. We get to fill in the intense gaps left by the film—whether they’re between Kerr and his girlfriend Dawn, or Kerr and his trainer, or Kerr and his superstitiously sexist colleagues, or Kerr and his college pals who help stage his opioid intervention—while Safdie spells it all out through obvious melodrama. It’s another concession to a wider prospective audience that Hyams never conceived of pandering to. It’s the small yet potent difference between a fascinating reality and an alienating fiction.

This would not be the last time John Hyams mined melancholy from the edges of action. Son of Peter Hyams (Timecop, Sudden Death), Hyams would make a few more documentaries after Smashing Machine, then take up the family tradition of directing Jean-Claude Van Damme. His final entries in the Universal Soldier franchise turned its super-soldier fantasy into a nightmare of eternal war. Finding the tragedy in the broken-down physiques of bodies built for violence became something of a specialty for Hyams. The hardships endured by Van Damme and Scott Adkins grew naturally from those endured by Mark Kerr. Even as the conflicts in his films escalated, Hyams knew that the vulnerable men at the center, the men who hated that they loved the constant fight, were the real draw.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.