Five years after the COVID-19 pandemic shut down the world, millions of people across the globe are still living with the unique ramifications of the virus and the way it transformed daily life. Yet in the ensuing years, those ramifications have rarely been depicted in television series. After an initial spate of Zoom specials and storylines set in the thick of the crisis, COVID became less of a factor onscreen. By 2022, the realities of coronavirus were referenced so little that outlets like The New York Times declared the pandemic to be “over” on television. But after years of minimizing a seismic event, 2025 marked a turning point with a slate of shows that returned to the topic. Half a decade later, television is finally reflecting how COVID changed things on a professional, personal, and even societal level.

The most obvious genre to tackle a medical crisis is the medical procedural. In the early days of the pandemic, The Good Doctor, New Amsterdam, The Resident, and Grey’s Anatomy all included coronavirus storylines. Meredith Grey (Ellen Pompeo) even contracted the disease and spent several episodes in a COVID-induced coma. But these hospital-set shows quickly moved past depicting the crisis and its lingering effects. One study found that “face masks are used only on rare occasions” on these shows after November 2020, while things like COVID tests are mentioned sporadically. Grey’s and The Good Doctor both prefaced new episodes with messages explaining that moving forward, their stories would take place in a fictional, “post-pandemic world.” Their vision for this world didn’t account for any changes that the virus wrought on the medical profession or the world at large.

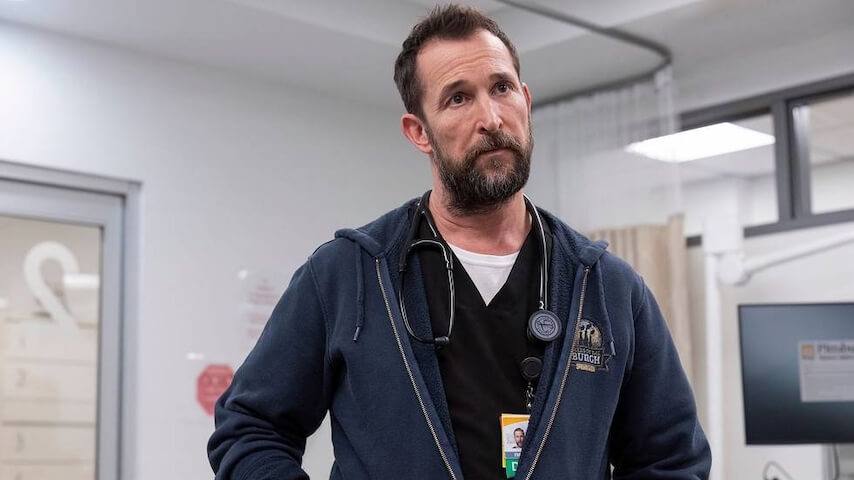

By contrast, The Pitt is a show entirely shaped by the consequences of COVID. Here, a straight line can be drawn from the fraying edges of the entire healthcare system—anxious and overwhelmed staffers, nursing shortages, resentful patients—to the pandemic. The entire first season takes place on the five-year anniversary of the death of Dr. Adamson, a leader in the emergency room and a mentor to Noah Wyle‘s Dr. Robby. Adamson’s loss looms large over these episodes, literalizing the practical and emotional consequences the pandemic had on the hospital. The Pitt‘s vision for a post-COVID world is decidedly not fictional but one that incorporates the major alterations brought on by the pandemic. It mirrors the struggles of actual medical professionals to rebuild after such a life-altering event.

This is made manifest in Dr. Robby, who suffers from COVID-related PTSD and experiences panic attacks and frequent flashbacks to 2020. The effects of working through the pandemic are not just professional for Robby but also personal. He grapples with the guilt of not being able to save his mentor, and it affects how he interacts with his patients and with his own mentees. On Ryan Murphy’s Doctor Odyssey, Dr. Max Bankman (Joshua Jackson) also suffers from COVID PTSD. In typical hyperbolic Ryan Murphy fashion, Max is said to be the first-ever COVID patient in the United States and nearly died from the virus. Where Robby’s traumatic experience with COVID drove him to work harder and commit even further to the hospital, Max’s drove him away: He decided to have more fun in his life and took a job on a cruise ship.

Unlike Meredith Grey, whose COVID coma is rarely referenced following her recovery, Max’s character is shaped by his experience contracting the virus. In the March 2025 episode “Sophisticated Ladies Week” (which aired in conjunction with the five-year anniversary of the U.S. coronavirus lockdown), Max puts a woman (played by Donna Mills) who tests positive for COVID into quarantine before contracting the virus himself. As patient and doctor debate his strict COVID protocols, it’s clear that Max’s personal experience in 2020 affects not only his handling of the case but also how he interacts with his co-workers and love interest (potrayed by Phillipa Soo), who’s supposedly pregnant with his baby. He admits his PTSD causes him to seek a greater sense of control over all aspects of his life, exemplified in his rigorous commitment to protocol and PPE in spite of those around him taking coronavirus less stringently years after the lockdown.

The different levels to which people take coronavirus prevention seriously in the so-called “post-pandemic world” are also depicted in Netflix’s animated comedy Long Story Short. The show, from BoJack Horseman‘s Raphael Bob-Waksberg, moves through time non-linearly, allowing it to demonstrate the differences of life before and after COVID. Frequently those differences are solely evident in the Schwooper family, who are depicted as the only ones still wearing masks after 2020. Others try to downplay the pandemic, like a mom at Hannah’s (Michaela Dietz) school who dismissively wonders if “anyone really [knows] anyone who died of COVID.” Avi (Ben Feldman) awkwardly reveals, “I mean, my mom did, so….”

Few television characters have ever died of COVID, let alone a main one. (A side character on NCIS was said to have passed away from the disease off-screen in between seasons.) So it’s significant that Schwooper matriarch Naomi (Lisa Edelstein) does. The first season doesn’t revisit 2020 but specifically focuses on the aftermath of losing Naomi in this very specific context. For instance, a funeral for another family member in 2022 triggers emotional responses. For Avi, all of 2020 was a “blur,” but his sister Shira (Abbi Jacobson) remembers all too well, resentfully recalling how “Mom got the novel coronavirus while everyone else got into sea shanties and sourdough. We had a Zoom shiva, and the Kleins couldn’t even click the link.”

Long Story Short often depicts the Schwoopers’ version of a post-pandemic world as frustrating and lonely, having experienced firsthand a loss that others only experienced from a distance. However, the show also delves into the broader psychological effects of living through the pandemic. Avi’s daughter Hannah struggles socially after losing her grandmother, watching her parents divorce, and having her schooling disrupted all in one short time frame. Abbott Elementary briefly touched on the difficulties teachers faced with remote learning in the 2025 episode “Strike,” but Long Story Short centers on how it affected students. Hannah faces a major setback when her school is overrun with literal wolves, kicking off a chain of events that sends the kids back into remote learning (which involves less learning and more online bullying). This “post-pandemic world” is fragile, where a funeral or a Zoom class can reopen old wounds and send the Schwoopers spiraling back into the worst period of their collective lives.

This concept is also touched upon in Paradise, Hulu’s post-apocalyptic murder mystery. The end of the world is a familiar setting on television, but Paradise‘s is a unique mirror to our own. It’s been three years since the apocalypse, and what’s left of American society lives in a giant underground bunker carefully designed to look and feel like life aboveground. But psychologist Dr. Gabriela Torabi (Sarah Shahi), who helped design the place, recognizes that the memory of the catastrophe is too fresh for the construct to be completely stable. “A shutdown would be like living everything all over again,” she warns. “The sheltering protocols, the illusion of the world being broken. The sky would go out. People would remember they’re living in a cave.”

It doesn’t take much to puncture Paradise‘s illusion. For Special Agent Nicole Robinson (Krys Marshall), when she returns for the first time to the entryway where she helped herd the traumatized survivors into their new home, it sends her spiraling into PTSD flashbacks akin to Dr. Robby’s on The Pitt. Protagonist Xavier Collins (Sterling K. Brown) is more like the Schwoopers on Long Story Short: The illusion of normalcy never really worked on him because of the personal grief of losing his wife. (Dealing with the death of a spouse also fuels much of this year’s Pluribus, a series that, while obviously not about the shutdown, taps into some of the isolation of that time.) But perhaps more than any other show aired since the pandemic, Paradise taps into the phenomenon of collective trauma. Everyone on the show has lost something, whether it’s a loved one, a lifestyle, or a physical sensation. When Torabi and Xavier wistfully list the tastes and smells they’ll never experience again—soft shell crab, summer peaches, the scent of a campfire—they acknowledge not only a shared reality but also the long-term, invisible consequences of a world-altering disaster.

Dr. Torabi, who calls herself an “architect of social well-being,” tells Xavier it’s good to talk about the things they miss, the life they had before. On Paradise, it’s a relief to acknowledge that the world did end. There’s a new world in its place that looks and functions similarly, but it is different. What was lost matters. What has changed matters. So much of television in the last five years has only offered the illusion of a “fictional post-pandemic world” at the expense of reflecting the one in which we actually live. Sometimes, it feels good for TV to puncture its own illusion.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.