Battle Royale's manga adaptation remains a gutting trip to the classroom

Ultra-violence and a good boy protagonist collide in one of the original death games.

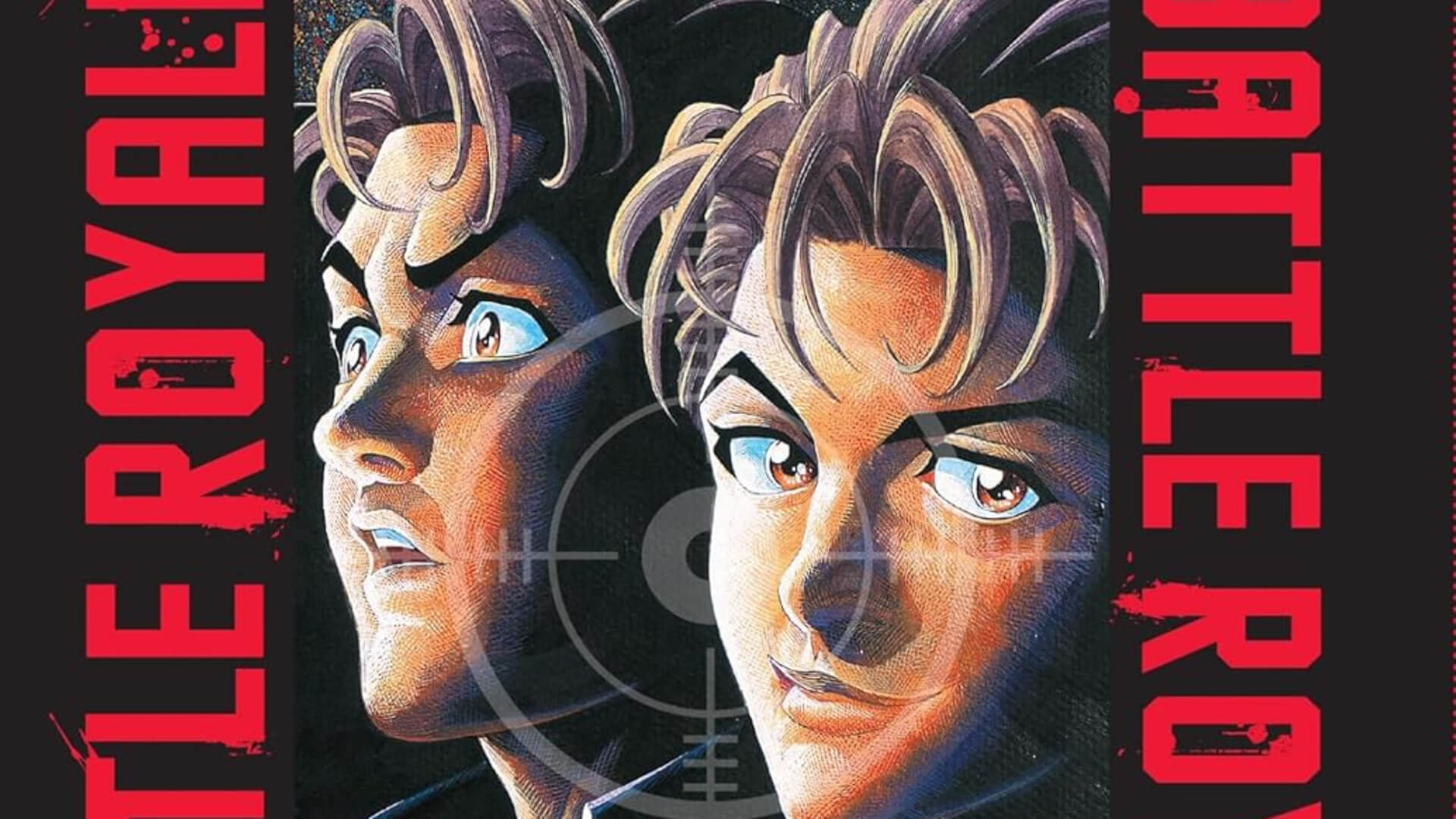

Image credits: Yen Press

It’s hard to think of many works in recent pop culture that have become as divorced from their original context as the 1999 novel Battle Royale. For the hundreds of millions who’ve logged into Fortnite, PUBG, or any number of other video games in this style, the term “Battle Royale” refers to a large-scale free-for-all mode where players can control a hodgepodge of popular characters like Darth Vader, Goku, the Xenomorph, and many more. The vague shape of the book and its many adaptations are there (i.e., fighting on an isolated island, collecting weapons, fleeing from danger zones, and the whole mass murder thing), but it’s all passed through a thoroughly gamified, Ready Player One-esque filter. Ultimately, any lingering symbolism is wiped out by a trash-talking teenager in a banana suit who just denied you a Chicken Dinner.

Considering that these games have sucked up most of the oxygen in the room, it’s all the more impressive that the original Battle Royale book and both its adaptations—the manga series and the film of the same name—still retain their horror, political acuity, and page-turning momentum decades later. As for the manga, which was also written by the author of the novel, Koushun Takami, its first three volumes (out of 15) were just released in English by Yen Press in a 600-page deluxe edition. While this technically isn’t the first time the manga has been translated into English, the previous version by distributor Tokyopop is quite controversial, having made significant changes to the plot and characters in an attempt to “westernize” it; by comparison, this new edition is much closer to the novel. It is nice to finally have a more definitive way to read it because, despite being dragged down by an overly blasé attitude towards sexual violence, the manga remains a cutting read that juxtaposes warm melodrama with bloodshed. Many stories may have drawn inspiration from this one, but there’s a rawness and specificity to this state-sanctioned killing game that remains uncomfortably gripping.

Given the glut of death game fiction in recent years, the setup will probably sound familiar. Every year, a fascist Japanese government (called the Greater Republic Of East Asia) picks several ninth-grade classrooms to participate in The Program. 42 students are trapped on a remote island and pitted against each other in a battle to the death, with only one survivor. They’re equipped with a supply bag that contains a randomized weapon and strapped to a bomb collar that will detonate if they disobey or remain in one of the island’s ever-changing “unsafe zones” for too long. As for the “participants,” there’s Shuya Nanahara, a counter-culture dissident who loves illegal rock music, his best friend, Yoshitoki Kuninobu, and Yoshitoki’s crush, Noriko Nakagawa. Outside this core group, there’s a long list of threats and unknowns, including the sociopath Kazuo Kiriyama, a genius gang leader, the praying-mantis-like Mitsuko Souma, who uses her looks to seduce her classmates, and the grizzled lone-wolf Shogo Kawada, who is initially an enigma. While some remain hopeful that they can solve things peacefully, it doesn’t take much of a push before a few of these teenagers start killing.

While that may sound predictably bleak, Hobbesian, and nihilistic, something that stands out about the manga is the intense sincerity of the protagonist, a good boy shonen hero dropped into a living hell. In his life before the games, he was a kind-natured kid at odds with the cruelty of the society he lived in, covering for others in big and small ways and standing up to bullies. Much of the tragedy stems from viewing this vile game through his empathetic worldview. At the same time, though, the character represents a refreshing underlying optimism: Despite everything he’s seen, his fundamental belief in people remains unbroken (at least so far).

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.