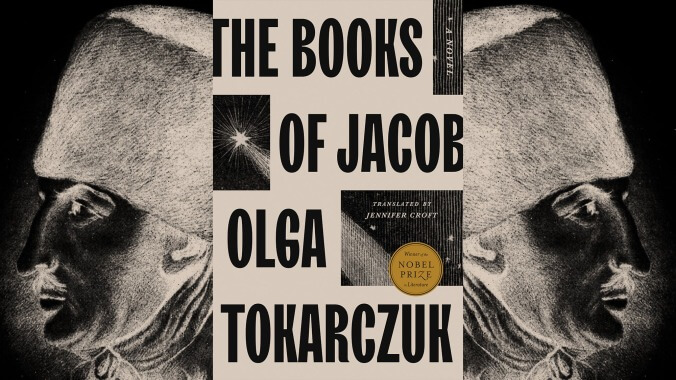

In The Books Of Jacob, a Nobel laureate tells the epic story of a self-proclaimed messiah

Originally published in Polish in 2014, Olga Tokarczuk’s 965-page magnum opus at last makes its way into English

Image: Graphic: Natalie Peeples

Books are always arriving at the wrong time in Olga Tokarczuk’s The Books Of Jacob. The 18th-century Eastern Europe and Mediterranean through which this novel charts its course is a thoroughly multilingual environment. It’s not uncommon for characters to juggle Polish, German, Yiddish, Turkish, and Ruthenian within a single conversation. Accordingly, writing moves at a much slower pace, and printing is often a matter of great personal cost. Official edicts take years before they’re translated into popular language, and heretical books are subject to censure and often burned. The Books Of Jacob also details prescient volumes that arrive too soon, and for that amount to prophecy. It’s appropriate then, that it should take a monumental amount of time, and deft translation work from Jennifer Croft, for this 965-page novel, which first appeared in the author’s native Poland in 2014, to make its way into English.

It comes with the recommendation of the Nobel Committee for Literature—which, in another example of bibliographic mistiming, retroactively awarded Tokarczuk the 2018 prize a year late, due to resignations at the Swedish Academy amid a #MeToo scandal. In the Anglosphere, little of Tokarczuk’s work had been made widely available at that time, and most reporting on the prize was devoted instead to 2019 laureate Peter Handke’s controversial support for Slobodan Milošević. The Books Of Jacob appearing now feels like a long-promised setting to rights, an occasion for English readers to experience a genuine global artistic event: the publication of a genre-broadening contribution to the historical novel.

For her subject matter Tokarczuk takes on the real-world figure of Jacob Frank, a Polish Jew who, beginning in the 1750s, claimed to be a messiah before leading his followers down a path of mysticism, apostasy, and often-dangerous adventure. Believed to be a reincarnation of the previous messianic claimant, Sabbatai Tzvi, Jacob Frank preaches a doctrine of liberation from the Talmud, Mosaic Law, and nearly every other cornerstone of conventional Jewish faith. In extraordinary times, according to Frank’s teaching, it falls to the messiah to transgress the old law and so herald the new. Scandalously, the Frankists convert to Christianity and face excommunication from the Jewish community. Only shortly thereafter, they’re accused of Christian heresy, and Frank is put in front of a tribunal. Religious disputation and changing political winds then find these true believers alternately embraced, embattled, imprisoned, or on the road within the roughly 40-year span of The Books Of Jacob’s principal action.

The magic of the novel is that an encyclopedically researched account of a fringe schismatic denomination from nearly three centuries ago should feel so wildly contemporary. At times, the long and abstract asides on Kabbalism can seem remote from modern readers’ concerns. But when the true believers establish their communitarian peasants’ republic on the site of a town abandoned by its previous inhabitants after a bout of plague, something of our own times’ apocalypse is brought into relief. The Books Of Jacob is studded with similarly affecting moments, in which both the proximity and the distance of the past are thrillingly, simultaneously affirmed.