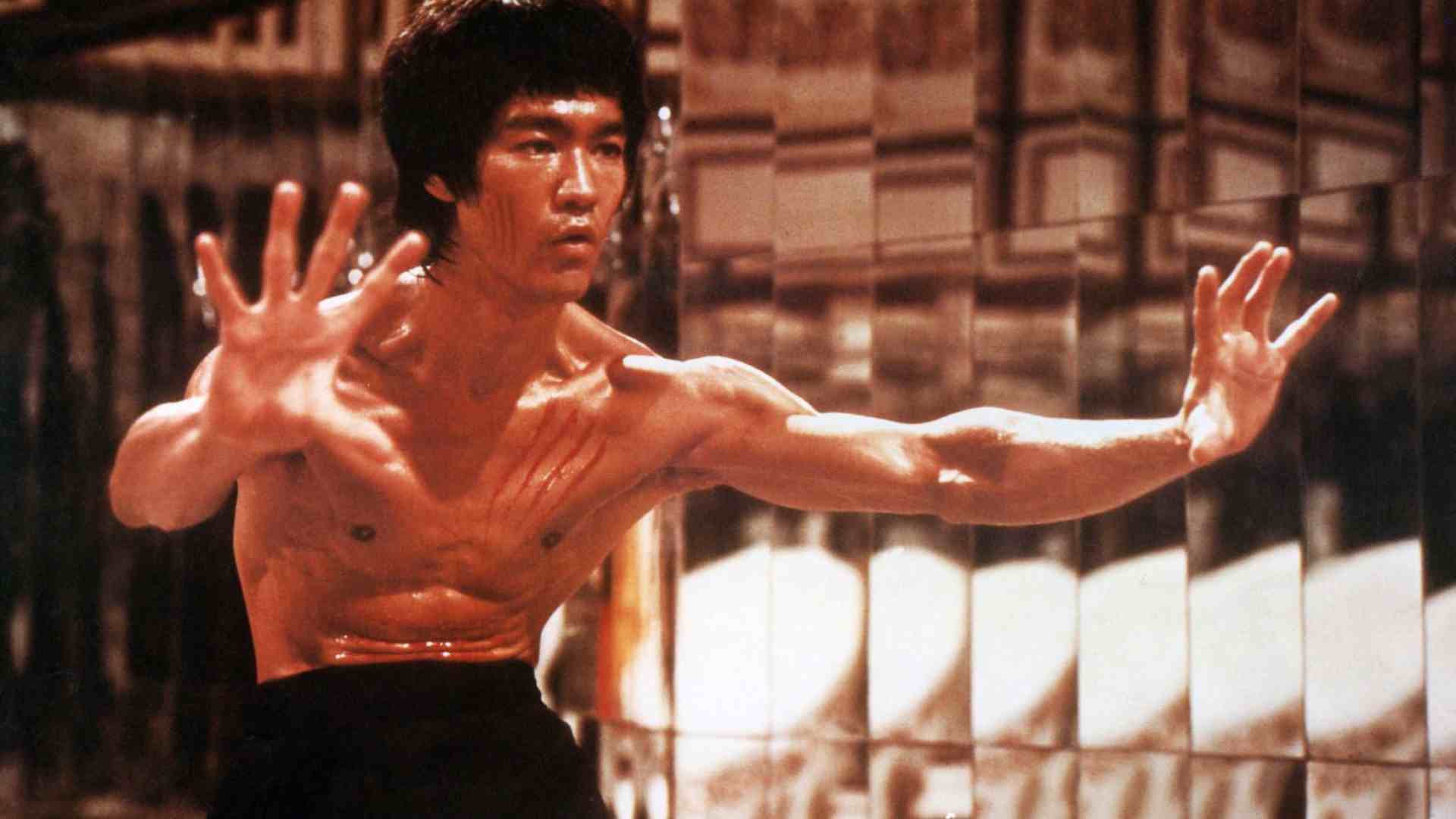

Bruce Lee reaches icon status with his final movie, Enter The Dragon

Photo: Warner Bros.

With A History Of Violence, Tom Breihan picks the most important action movie of every year, starting with the genre’s birth and moving right up to whatever Vin Diesel’s doing this very minute.

Enter The Dragon (1973)

When any Asian action star finds a certain level of fame abroad, it’s practically inevitable that he (or, in a few cases, she) will eventually make the trip to Hollywood. It doesn’t always work out. In the last few years, Tony Jaa and Iko Uwais have made some small inroads. Jackie Chan became a huge crossover star, but only on his second attempt, in the mid-’90s; his first try, with 1980’s The Big Brawl, was a resounding flop. Jet Li did pretty well for himself. Donnie Yen has mostly stayed away, other than some smaller, more exploratory roles. Takeshi Kitano made a movie with Omar Epps. Chow Yun-Fat was reduced to mustache-twirling in the worst Pirates Of The Caribbean movie.

Enter The Dragon came before all of that. Bruce Lee’s fourth and final movie as a kung fu star was the only one he made in English, with an American director and American stars. It’s still, at least partially, a Hong Kong movie, with the whole thing being filmed in Hong Kong and Golden Harvest boss Raymond Chow serving as co-producer. But it’s very much a Western take on the kung fu movie, which was then a genre in its infancy. Lee had only been a movie star for two years, and the craze-starting The Chinese Boxer was just three years old. And so Enter The Dragon qualifies as a fascinating experiment, an attempt to see whether this new foreign subgenre will work in a more American context. Even though the movie was, in a lot of ways, a glorious mess, it turned out to be a huge success on just about every level.

Lee wasn’t exactly the auteur behind Enter The Dragon, the way he was with The Way Of The Dragon, the movie he made immediately beforehand. He ceded the director’s chair to Robert Clouse, who’d only made a few movies and who would never make anything anywhere near this iconic again. But Lee was still the primary creative force behind the movie. He co-wrote it, put together its great action scenes, and made sure to put his personality in there whenever possible. Early in the movie, there’s a weird scene in which Lee, talking to a young student, insists that the kid put “real emotional content” into his kicks, and then Lee spends the rest of the movie trying to show us what a kick with real emotional content looks like.

The whole movie is designed as a Lee vehicle. He gets to talk a bit about philosophy, about his idea of “the art of fighting without fighting.” He gets all the best scenes and coolest moments. He plays a character named “Lee,” and it feels less like a character and more like the man himself. Lee, of course, understood what he’d need to do in a movie for American audiences. He’d lived much of his life in the U.S., played Kato on American TV, and played small roles in a few American movies. He knew what he was doing. And with American production values, as well as an ice-cold funky score from the great Lalo Schifrin, Lee ended up looking cooler than he ever had before. (Schifrin was one of the MVPs of early action cinemas. I’ve written five of these columns thus far, and three of them are for movies with Schifrin scores.)

But even with Lee dominating the movie, there is some typical American-studio fumbling in there. When Lee and the movie’s other fighters arrive at the evil-mastermind fortress where they’re having their death tournament, they all sit down for a banquet in a room full of generic stereotypical Asian touches: acrobats, sumo wrestlers, a Chinese New Year dragon. The bad guy, Han, is practically a parody of the scheming Bond villain; he pets a fluffy cat and says stuff like, “We are investing in corruption.” And the movie dedicates a baffling portion of its running time to two heroes who are pointedly not Bruce Lee.

Honestly, though, Enter The Dragon got pretty lucky with those two heroes. One was John Saxon, an American character actor whose face will be familiar if you’ve watched enough old movies. Saxon had been working for years; he was playing juvenile delinquents in the ’50s. And he’d keep working for years afterwards, playing Nancy’s police-chief father in A Nightmare On Elm Street. Saxon had fun playing a gambling-addicted international-playboy type, and his screen fighting was better than anyone could’ve reasonably expected; it’s a bit weird he didn’t stick with kung fu movies after this. Meanwhile, the towering, beautiful, magnificently Afroed karate champion, Jim Kelly, who had never been in a movie before, was a total find. Kelly’s character was a black-power archetype, not really a character at all, but he had the charisma to carry it off, and I love the scene where, when offered a night with a prostitute, he picks four of them and then apologizes for not picking more. Kelly’s screen fighting was pretty impressive, as well.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.