John Darnielle’s Universal Harvester can’t reap the benefits of its intriguing premise

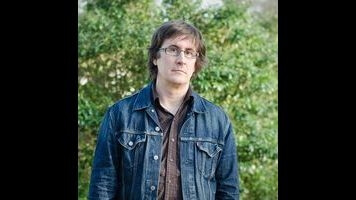

“In most lives, in most places, people go missing.” The first line of the final chapter of John Darnielle’s second novel, Universal Harvester, makes clear its main concern. Although Darnielle, best known as the singer-songwriter behind indie folk outfit The Mountain Goats, begins the novel as one story—a mystery or thriller, complete with the Rings-like allure of old technology—it transforms into a quiet tale of absences and what they render in the lives of those left behind.

One of those lives belongs to the novel’s ostensible protagonist, 22-year-old Jeremy Heldt, who cohabitates with his father and works at the Video Hut in the small town of Nevada, Iowa. Jeremy’s mother died six years prior, in 1994, in a car accident, and the two men have since fallen into a predictable-to-a-fault routine of simple dinners and movie-viewing, and a tendency not to probe too deeply into one another’s feelings. Their calm melancholy is disturbed when Jeremy learns that odd, out-of-place scenes have been appearing in some of Video Hut’s VHS tapes: first, cryptic black-and-white videos of empty barns, accompanied by heavy breathing, then people in the barn with canvas bags over their heads, standing or sitting or shuffling around with unclear purpose. Though disturbed, Jeremy spends much of part one debating what—if anything—to do with this information.

Like Jeremy, many of Universal Harvester’s characters suffer from an extreme passivity, too scared of seeming rude or overstepping to act, and the story, unfortunately, suffers for it, too (it’s the rare compelling character whose defining trait is polite ambivalence). The narration often chalks up this and other behavior to the characters’ Midwestern background. For example, Jeremy’s relationship with his taciturn co-worker is described like this: “[T]he governing silence between them was the regional grammar of comfort between like-minded men.” It’s a lovely turn of phrase, but it reinforces a cliché, which does no favors in distinguishing these individuals. Darnielle often justifies his characters’ actions more generally, too, instead of letting readers perform their own interpretations, the prose becoming clotted with such exposition. They are nearly all “good people” (Darnielle loves his characters almost to a fault), with the novel’s scarce violence downplayed to near erasure, lest it keep readers from sympathizing with its perpetrator.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.