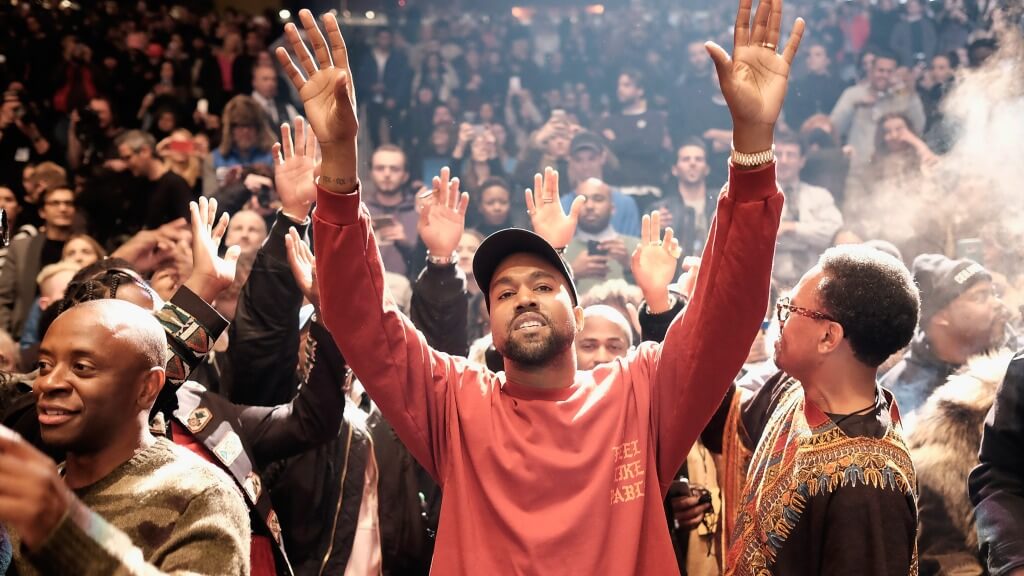

2016 marked the beginning of the end for Kanye West. The formidably talented rapper had been courting controversy throughout his career, with his inflammatory behavior always teetering on noxious and alienating, but his creative genius, madcap sense of humor, and command over the culture immunized him from reputational ruin, as did the public rationalization around his fraying mental health. Much of the discourse around West started to change for the worse, though, following the release of his seventh album: The Life of Pablo.

The record immediately stood out as West’s messiest and most excessive work, as well as his most fascinating and naked. In contrast to the conceptual rigor of 2013’s masterful Yeezus, The Life of Pablo was thoroughly anti-concept, distilling West’s most distinctive traits—gospel-inflected hip-hop, braggadocious lyrics, soul samples, ad-libs, and hooks from a stacked rotation of game collaborators—into one delirious, id-driven elixir. Just as notable was West’s obsessive tinkering around The Life of Pablo, informing the many months of hype and delays around the album and the multiple tweaks made right before and after its release.

Random as it sounded then, The Life of Pablo was the most fitting title for a record unable to stick to one singular, cohesive idea, gesturing at a trio of prominent figures who each reflected West’s conflicting identities: the devout Christian (Paul the Apostle), the boundary-pushing artist (Pablo Picasso), and the infamous provocateur (Pablo Escobar). The cover was equally chaotic, a mesmerizingly hasty Photoshop job that juxtaposed West’s yearning for groundedness and hedonism with two drastically different images (an old family photo and a shot of a model Sheniz Halil’s scantily clad ass), both superimposed over a Fanta-orange background and bold, black lettering that spells out the title and the enigmatic phrase “WHICH / ONE.” The album was, in essence, 2016 in a nutshell: a year marked by some fantastic strides in entertainment as well as tons of grief, death, confusion, and foreboding omens for what was to come.

A few elements from The Life of Pablo show their age—Chance the Rapper saying “I met Kanye West / I’m never going to fail” is bound to elicit a disappointed “awww,” and the belabored feud between West and Taylor Swift prompted by his line about having sex with her now registers as a fuzzy memory—but the album still plays rather well a decade later, all things considered. It remains charming in its unpolished, freewheeling energy; disarming in its emotional honesty; and amusing in its gleefully irreverent songwriting, which comes off as almost refreshing by today’s hyper-sanitized standards. However, in the years since, The Life of Pablo has taken on a more mythological quality, now standing as the definitive end to a hot streak for a once-great artist who’d go on to heed his worst impulses to an irreconcilable degree.

It’s impossible to talk about and listen to this album—and any other music made by West, for that matter—without thinking of the many awful, wrongheaded things he’s said and done over the past ten years: there was his endorsement of Donald Trump for president; his smug declaration of slavery as “a choice”; his troubling, MAGA-pilled rant to a captive Saturday Night Live audience and cast; two failed runs for president of his own; his opening of a private Christian academy that closed after accusations of fraud; his concerning threats against his ex-wife Kim Kardashian and their family; the string of sexual assault allegations against him; and of course, his anti-Semitic screeds and embrace of Nazism, an ideology he’s allegedly been interested in for over 20 years. The list goes depressingly on. Though he recently apologized for his right-wing beliefs, chalking up his bigotry to his longtime struggle with mania and an untreated head injury from a 2002 car accident (which inspired his breakthrough single “Through the Wire”), West has burned far too many bridges to undo or forgive his actions.

As a longtime Kanye fan, it was difficult watching him gradually crumble under the weight of his own self-sabotaging decisions, but such a demise seemed inevitable. West’s career has been defined as much by his ability to make gorgeous music out of the pain of the past—his own and that of the Black musicians whose work he frequently referenced—as it has been by his inability to censor his thoughts, no matter how outrageous they were. His voice was his greatest weapon, but it was only a matter of time before it transformed into a tragic flaw. Being surrounded by nonstop adulation, boatloads of wealth, constant media scrutiny, and sycophantic enablers only seemed to propel West deeper into psychosis, and having a celebrity also known for his brazen, logorrheic personality become the leader of the free world emboldened West’s narcissism to an ugly point of no return.

West himself seemed to know what kind of unruly behavior he could get away with and how terrifying possessing that kind of power could be. On The Life of Pablo, West directly contended with these exact feelings, opening up about all the gifts bestowed to him and the curses, both external and self-imposed, that threatened to take them away. The tension between these incongruous temperaments matched the album’s sonic overflow as well: A Metro Boomin beat and T.L. Burnett classic could exist on the same song as a desperate plea for liberation and a bleached-asshole joke (“Father Stretch My Hands Pt. 1”). The trill of Desiigner’s “Panda” could act as an urgent springboard for West’s stunning speed-run through his traumas (“Pt. 2”). Frank Ocean could interpolate Sia (“Wolves,” “Frank’s Track”) and Rihanna could interpolate Nina Simone (“Famous”).

Rihanna, or rather a lifelike wax model of her, is featured in the infamous tableaux of naked celebrities (Donald Trump, Caitlyn Jenner, George W. Bush, Taylor Swift, Amber Rose, Bill Cosby, Anna Wintour, Chris Brown, Ray J, and Kim Kardashian) sleeping in the same bed in the “Famous” music video, which used demented visuals to bring our culture’s voyeurism into unsettlingly sharp focus—albeit also warranting legitimate discomfort and discourse around sexual harassment and showing someone’s naked body without their consent for art’s sake. It’s technically not his final album, but considering the dystopian implications of the “Famous” clip, the desperately packed footnotes, and sporadic allusions to brushes with death, The Life of Pablo plays like one. And knowing the kind of persona non grata West would morph into, it does, in a sense, feel like the last gasp of the old Kanye, something West would self-reflexively comment on in the acapella interlude “I Love Kanye.”

Despite the sweaty execution, there are still glimmers of brilliance within the patchwork-like, densely layered designs that shine through: the spiritual swell and Chance the Rapper’s infectiously giddy (if now slightly dated) verse on “Ultralight Beam”; the gobsmacking carnal candidness and sinister Swizz Beatz production on “Famous”; the Ray J diss on “Highlights”; the heavenly stuttering instrumental on “Waves”; the wild turns of phrase on “Feedback”; the My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy throwback vibe on “No More Parties in L.A.”; and the bitter grit and ghostly bounce of “Real Friends.” That last track in particular is one of West’s greatest achievements and best articulates the album’s themes: a lucid and sad chronicle of his exhaustion dealing with opportunists and desire to maintain some semblance of authenticity in his relationships. “Saint Pablo,” a late addition to the tracklist, is a haunting bookend, operating three-fold as a blistering critique of institutional racism, a sincere confession of his addictive money spending, and a harrowing self-fulfilling prophecy, in which West documents the public’s obsession with his mental health while dismissing his need for help: “I’m not out of control / I’m just not in their control.”

West’s inability to be in control, of course, would ultimately be the very thing that led to his undoing, and despite the slight sadness of the Kanye we all once knew no longer existing, his current exclusion from the cultural spotlight is for the best. Most, if not all great artists are terrible, deeply wounded people forever tethered to their trauma, exploiting their pain while trying to make sense of it. For all of its rascal-like trolling and scatterbrained nature, The Life of Pablo is not only a testament to that contradiction, but a glimpse into a fraught psyche struggling to keep up the facade at a time when the world was struggling to keep up its facade before both inevitably collapsed.

Sam Rosenberg is a filmmaker and freelance entertainment writer from Los Angeles with bylines in The Daily Beast, Consequence, AltPress and Metacritic. You can find him on Twitter @samiamrosenberg.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.