Despite those superficial similarities, though, Neruda is ultimately a very different film than Jackie, and arguably the bolder of the two. Its palette is darker, even as its sensibility is less somber, more playful. Most significantly, Neruda, written by Guillermo Calderón (who also penned Larraín’s other 2016 U.S. release, The Club), achieves a synthesis between content and form that Jackie notably lacks. Rather than having characters merely talk about the distinction between grim reality and expedient myth, this film builds that distinction into its very structure, giving Neruda a fictional antagonist ostensibly invented by Neruda himself. It’s a thriller in which the thrills are manufactured, and everybody on screen knows it.

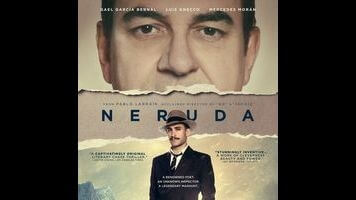

At the beginning of the film, Neruda (Luis Gnecco) is still in the Chilean Senate, to which he was elected in 1945. After denouncing President Gabriel González Videla (whom he’d supported) in a speech on January 6, 1948, however, the beloved poet suddenly finds himself the target of the same repressive, anti-communist policies against which he’s fighting. Neruda covers the roughly 13 months Neruda spent in hiding before he finally managed to escape to Argentina, where he spent another three years in exile. Much of that time was spent writing his epic poem Canto General, but the movie introduces a dapper police inspector, Óscar Peluchonneau (Gael García Bernal), whose relentless pursuit of Neruda is accompanied by philosophical voice-over narration in which he acknowledges that he’s a fiction—his quarry keeps leaving detective novels for him to read, either as homework or just as a means of mocking his ineptitude—and repeatedly grumbles about being treated as a minor supporting character.

Gnecco deftly sidesteps the usual pitfalls of Great Man biopics, creating a flesh-and-blood character who never seems beholden to a Wikipedia synopsis; his Neruda is alternately grandiose and irritable, willing to constantly recite, by drunken request, what was then his most famous poem (an untitled work that begins “Tonight I can write the saddest lines”), but equally prone to self-importance when talking to his wife (Mercedes Morán), at whom he snaps at one point, “Kill yourself if you want to. That way, I’ll write about you another 20 years.” But it’s the Pirandello-esque self-interrogation of the imaginary inspector that elevates Neruda above the vast majority of biopics. García Bernal is confident enough as an actor to do virtually nothing, allowing Larraín to sculpt a void of a performance around his classically handsome features (which look superb beneath a fedora and adorned by a pencil mustache). The movie’s meaning resides in the deliberate disconnect between Peluchonneau’s iconic film noir presence (enhanced by cinematographer Sergio Armstrong’s aggressively digital photography, which creates silhouettes that look as if they’re encased in crushed velvet) and the detective’s increasingly inquisitive voice-over, over the course of which he comes to realize his importance in creating Neruda’s legend as a persecuted man of the people. The more Neruda departs from historical fact, the more trenchant it becomes. Take note, other filmmakers.