Primer is The A.V. Club‘s ongoing series of beginners’ guides to pop culture’s most notable subjects: filmmakers, music styles, literary genres, and whatever else interests us—and hopefully you.

The world painted by Kiyoshi Kurosawa is one of disaffection. The Japanese auteur has made a career of identity thrillers, metaphysical horror, and cultural commentary, with films often sporting deceptively simple monosyllabic titles—Cure, Pulse, Chime, and now Cloud—that circle around existential themes. What is personal or cultural identity in contemporary Japan? How does economic precarity and technology transform the self? Do they always create the conditions for self-destruction and violence? Finally, and maybe most importantly, why does this movie feel like that? The quiet, unceremonious editing, the sudden bursts of violence, an abundance of negative space, and the sparse but abrupt use of score all conjure an eerie mood that can be difficult to parse but impossible to ignore.

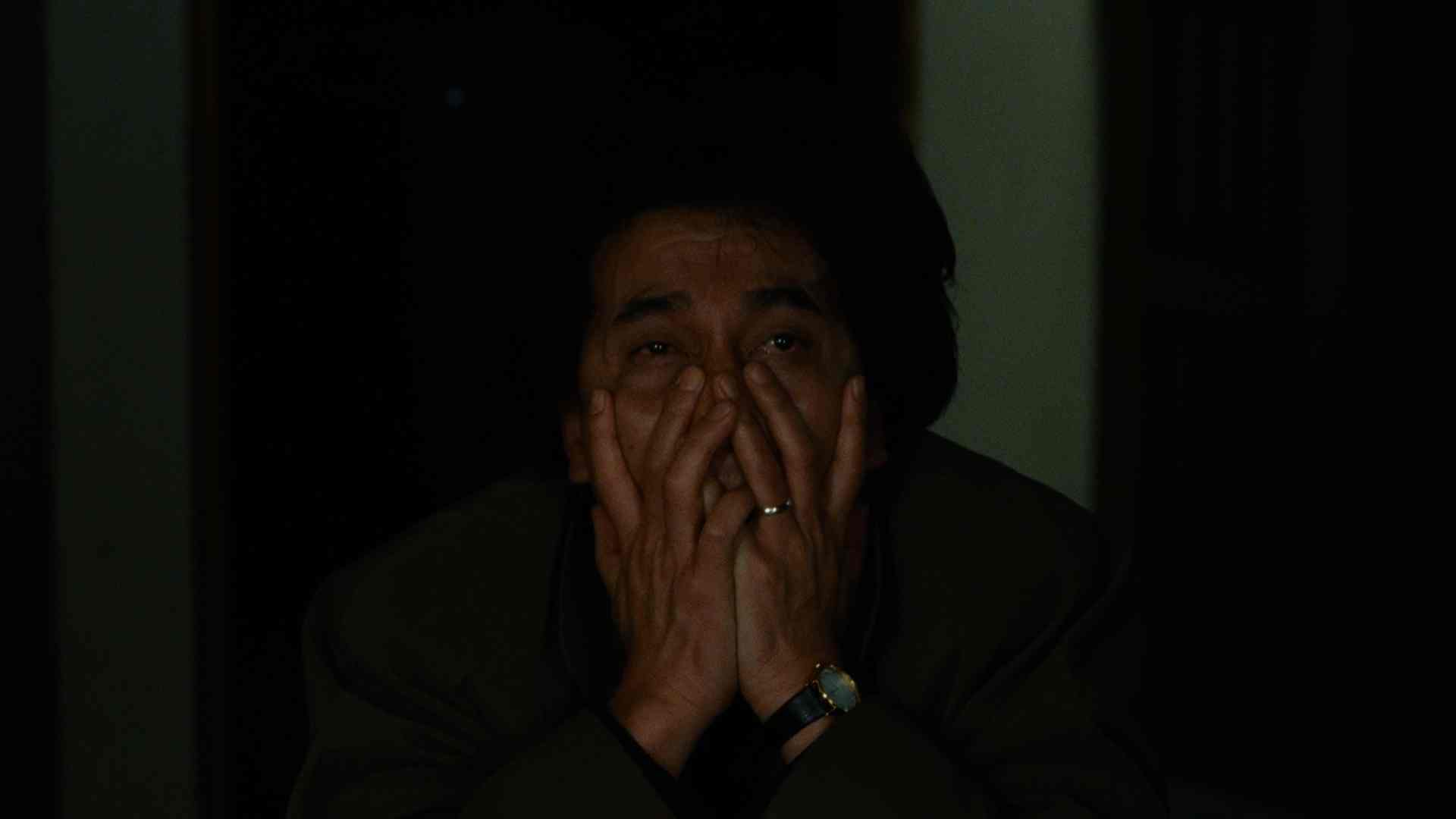

Isolated stills from Kurosawa’s films may look unassuming or unremarkable—perhaps a plain domestic room or the floor of an abandoned factory, with two or three characters separated by clear lines and empty space—but when you’re immersed in the scene, every image is loaded with strangeness and dread. Why have they stood still for so long? Why are their voices so soft and muted? What’s that ambient, industrial whine in the background? What’s upset Kōji Yakusho this time?

The latest Kiyoshi Kurosawa thriller to ask these questions is Cloud—at once an exciting and funny genre exercise, a commentary on the vulnerability and inhumanity of online grifter culture, and only one third of the films that the prolific filmmaker premiered in a year’s span. In the film, Yoshii (Masaki Suda) is an internet reseller who values his independence even as he profits off the inventors and workers he screws over. But the success of his growing enterprise makes him an especially isolated target for a vengeful mob that gathers in the wake of his eat-or-be-eaten business strategy.

It’s a lively, amusing, and incredibly off-putting romp (especially in its final stretch, where supporting characters undergo metaphysical transformations), and an apt update to the themes of spiritual alienation and abandonment that have lingered in Kurosawa’s work for decades. For the uninitiated, here’s a primer to the work of Japan’s most titanic genre filmmaker.

Kiyoshi Kurosawa 101: A Supernatural New Millennium

There’s no more apt and scintillating doorway to the world of Kiyoshi Kurosawa than Cure (1997). Pitched as a thriller about a detective on the trail of an enigmatic killer, Cure has a chillingly subdued surface that mirrors the conventions of Hollywood’s post-Silence Of The Lambs serial killer boom, but expresses them with a decidedly restrained voice. Detective Takabe (Kōji Yakusho) is on the case of the mysterious “X” killer, named for the carved-in-flesh symbol that links a slew of inexplicable murders. Each bout of violence has a clear culprit with a relationship to the victim, but their confessions can’t account for why they committed an act of horrid violence. A drowsy and absent-minded young man (Masato Hagiwara) has asked each needling questions, which have seemingly tipped each unsuspecting murderer over the edge. The mumbling amnesiac (and his lighter) become an obsession for Takabe as he marches closer to the heart of the case.

Mesmerism plays a crucial role in Cure‘s plot, but Kurosawa uses the study of hypnosis as an entry point to broader, more upsetting questions of identity and will. Is identity fixed? Is behavior dependent on a stable environment, and on avoiding specific stimuli that unleash our dark, selfish impulses? The characters in Cure sit on a precipice of understanding, if not their true selves, then their inherent helplessness in the face of their ugly desires. As a thriller, it’s elliptical and sparse, sometimes leaping to the next strangely empty composition (or even the end credits) right after dropping a striking and revealing image.

Lingering behind Takabe’s plight is his own capacity for violence. His wife Fumie (Anna Nakagawa) suffers from schizophrenia, and disassociates at regular intervals. Takabe is a neglectful, resentful husband; the scenes he shares with Fumie are pent up with his silent shame, and his frustration with her abnormal behavior. In one memorable moment, he comes home and hallucinates that she’s hanged herself in the kitchen. He’s still on his knees in agony when Kurosawa cuts to Fumie standing behind him, alive as ever. Takabe sees her death because he’s imagined it—dreamed of it—before.

The motif of death imposing itself on an unsuspecting but not entirely innocent soul is a profoundly Gothic idea, and two genre-mixing ghost stories by Kurosawa are essential next steps for those seeking out his major hits. Retribution (2006) plays in more traditionally supernatural waters than Cure, but belongs to the same family, as it also stars Yakusho as a beleaguered, haunted detective. (See also: Kurosawa and Yakusho’s environmental identity thriller Charisma.) In Retribution, Detective Yoshioka (Yakusho) looks into a Tokyo waterfront murder, but his investigation begets some troubling contradictions—including the fact that he is the most likely suspect. His complicity is compounded by a repeated sighting of a gaunt, flowing female ghost, dressed in vibrant, incriminating scarlet colors, who teases out the connection between Yoshioka and the woman in red when she was alive.

Kurosawa transposes Gothic questions of complicity, repression, and apathy to a modern, urban Tokyo, making Retribution the next step in a career-long exploration of what the enforced atomization of a society does to our humane responsibilities. What does a cry for help look like when it’s been denied oxygen for years, even past the boundaries of life and into the spectral realm of death? To Kurosawa, the scary, inhuman presence of ghosts is unavoidable, and has a clear causal explanation. Modernity—with its defensive, individualist imperatives of self-protection and betterment—bludgeons compassion and connection.

If Cure preceded the most essential films in the J-horror boom around Y2K (Ringu, Ju-On: The Grudge, Audition), then Kurosawa’s Retribution and Pulse (2001) are reacting to the genre movement’s immense commercial appeal and influence. In Pulse, the recently emerged instant communication of the world wide web becomes a pathway for lonely, mournful spirits to spill back into our world, so helpless and desperate are they in the vast prison of the afterlife. Pulse is less subdued than Cure, but has a quieter pitch than Retribution, spending a lot of its scenes in students’ humble living quarters or mundane computer labs—a mundanity broken by sudden visitations, rituals sourced from web forums, and friends succumbing to invisible, self-destructive urges.

Nearing its quarter-century anniversary, Pulse has outlived its early internet context, now more of a prophesy about the cursed promise of online hyper-convenience: The vessels and channels of the internet will inevitably allow for infinite distress and sadness to pour into our private worlds, impossible to ignore or be unaffected by, until pain we thought forgotten or irrelevant overrides every waking moment.

Intermediate Work: Dispossession In The Lost Decades

Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s unique horror cannot be fully appreciated, on the level of both craft and themes, without sampling his more straightforward dramatic work. Across three dramas—License To Live (1998), Bright Future (2002) and Tokyo Sonata (2008)—Kurosawa makes unusual revisions to traditional family structures to reflect a fraught and shifting Japanese society.

The disaffection and disconnection that characterizes Kurosawa’s modern Japanese films was born out of a distinct national mood. After emerging as the world’s second biggest economy in the 1980s, Japan’s economic growth abruptly collapsed after an asset bubble burst in the early ’90s, leaving a stagnant real estate and stock market landscape that affected the entire country. The era following this would be referred to as the “Lost Decade.” With three films made across 10 years, Kurosawa told stories of alienation that gives birth to hopeful renewal, while avoiding the worst defects of sentimental melodrama. In fact, even in these grounded films he maintained most of the tenets of his dread-inducing, purposefully empty, and emotionally decentering style.

The plots are all unique but share connective tissue: In License To Live, 24-year-old Yutaka Yoshii (Hidetoshi Nishijima) wakes up from a 10-year coma in a state of adolescent ennui. He’s woken up to a world with no Iron Curtain and no Japanese economic growth, and his small family (his parents and sister) live independently from each other in different states of modest living. When Yoshii is taken in by his father’s childhood friend Fujimori (Kōji Yakusho), he attempts to unite his disparate family despite their disinterest. In Bright Future, the lives of two young factory workers are turned upside-down when one (Tadanobu Asano) kills their boss as revenge for his bothersome intrusions on their life. The other worker (Joe Odagiri) is entrusted with their shared jellyfish and strikes up a friendship with his incarcerated friend’s father (Tatsuya Fuji), even as anti-social unrest and vandalism starts to dominate the young man’s life. The most acclaimed of the three, Tokyo Sonata, details a family spiraling in the wake of a father’s redundancy. Here, adolescent rebellion takes the form of both clandestine piano lessons and joining the U.S. military, and a father’s shameful employment problems intersect with a housewife being kidnapped from her domestic sphere by a burglar.

Kurosawa’s family dramas are not exclusively tied to social interpretations of this “Lost” era (some commentators say it lasted for 30 years), but like many films concerning social relations and expectations, the stories include a single but crucial change that affects every character’s life. No matter how hard they try, the past cannot be recovered or rebuilt, and fractured families have to face their newly tested and often diminished status in order to reconstitute themselves. Rarely are characters on the same page—just like the schemes and murders of his genre pictures, Kurosawa maps out his dramas with independent wills and drives that can only run alongside each other for a brief time before they combust or fall to disorder. These films are about capitalism’s promise falling woefully short, but Kurosawa ends each on a bittersweet hopeful note, showing a remote but clear possibility to transcend these punishing conditions.

Advanced Studies: Commercial, But Not Minor

Kiyoshi Kurosawa has made so many films (averaging out to one a year for 40 years) because most are overwhelmingly commercial projects made cheaply. “Foreign directors ask me, ‘How come you make so many movies?'” Kurosawa told Film Comment in 2017, while promoting his French-language Gothic film Daguerrotype. “And I say, ‘Well, if I’m not working, that means I’m unemployed.'” His career is not one of pure auteurist expression, but of constantly navigating industry restrictions—the first decade-and-a-half of his filmography consists of “pink” films (independent films with sexual content), horror oddities, and Yakuza sagas. Early highlights from before his international breakthrough include The Guard From Underground, about a murderer disguised as an office block’s security guard and the haunted house thriller Sweet Home, which was released alongside a video game of the same name that inspired Resident Evil.

Watching Kurosawa’s Seance (a sterling TV movie adaptation of the British novel Séance On A Wet Afternoon) or Doppelganger (a comedic thriller about duality that saved money by giving star Kōji Yakusho double duty), one can tell that his production resources are tight. But the naturalistic conversations and grungy, ugly environments are still animated by entrancing and startling editing. Kurosawa’s power lies in his films’ beguiling rhythm, one the audience fears will be interrupted at any moment by something outside the characters’ control.

The most underrated films in Kurosawa’s catalogue never got a theatrical release at all—during his wildly prolific run at the end of the century, (he released 11 films from ’96 to ’98), Kurosawa added to his V-cinema filmography with a pair of 1998 revenge films: Serpent’s Path and Eye Of The Spider. In both films, an ordinary man loses his daughter and hunts down the sadists who killed her; in each film, Kurosawa chooses a different moment in a conventional Yakuza revenge story to examine under a microscope, letting his distressed and violent characters flounder within criminal organizations and under the mentorship of criminal professionals who promise they have their best interests at heart.

Kiyoshi Kurosawa films don’t get more stripped-back and nasty than this. Inside abandoned industrial caverns, righteous men inch closer to a brutal clarity, deluding themselves with the hope of closure and new beginnings, but really only sign a series of contracts with a mean, bureaucratic Devil taking advantage of their unmoored psyches—an unsubtle but gut-punching metaphor for the grasp of capitalism on modern Japan. Pull a double feature with both, and one can lose their certainty about the nature of good and evil in less than three hours.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.