There’s good reason to be skeptical of white filmmakers taking on the Black experience. But if Green Book, as a recent and obvious example, demonstrated the pitfalls of trying to tell someone else’s story, What You Gonna Do When The World’s On Fire? shows that it’s not impossible to do it respectfully. This is the fifth film about the American South from the Italian-born documentarian Roberto Minervini, but his first to follow Black subjects, living their lives in Louisiana and Mississippi.

Those familiar with Minervini’s past work — the resentful malaise of white Southerners on the fringe in The Other Side, the bristling coming of age of a religious teen girl in Stop The Beating Heart—can attest to the baffling middle ground between fiction and documentary that he stakes. The private moments Minervini captures, paired with a heavy use of in-your-face close-ups, creates the illusion of scripted (if highly naturalistic) drama. What You Gonna Do When The World’s On Fire? similarly confronts the inner lives of its subjects, but is less driven by narrative and more democratic in the attention it lavishes on four unconnected stories. Filming in sharp black-and-white that bridges the past with the present, Minervini eschews didacticism and activism, focusing instead on the raw, emotional textures of his subjects. The results are often beautifully immersive.

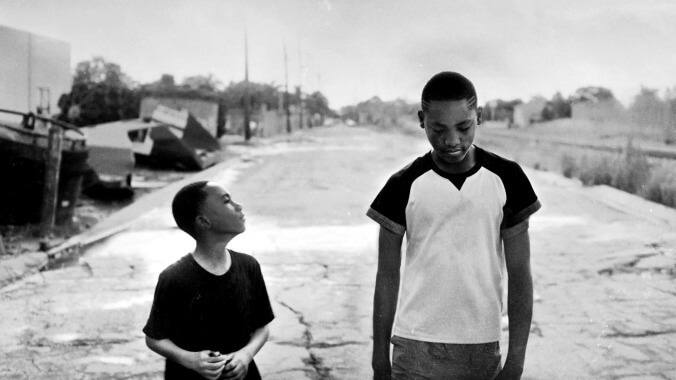

Minervini begins by introducing a pair of brothers, teenage Ronaldo leading fearful 9-year-old Titus through a haunted house. Meanwhile, the Mardi Gras Indians, a group that celebrates the common heritage between West African and Native American cultures, dance and parade through the night streets to the thundering sounds of chanting and drumming. The revelry is cathartic and joyous, but also tinged with militancy and a sense of upheaval—a response to the distressing allegory Minervini identifies in the brothers’ story. Through Ronaldo and Titus, we see not only how some children are forced to grow up fast, and pass down knowledge of how to survive in an inevitably terrifying world, but also the toll this has on childhood impulses, behaviors, and expectations.

Next comes a street-side protest organized by a chapter of the New Black Panther Party, mobilized in the aftermath of racially motivated murders ignored by the police. Minervini follows the group, led by Krystal Muhammad, as they conduct official activities—protesting, feeding the homeless, launching door-to-door de facto investigations on community killings. This thread is less personal than the others, perhaps because the Panthers are more guarded about how they’re perceived, yet their routine activities are riddled with gut-punch reminders of the brutality they’re up against: violent police pushback, harrowing acts of intimidation by the local KKK.

Then there’s Judy Hill, an abuse survivor and the owner of a New Orleans bar and meeting space whose arresting personal confessions and powerful moments of camaraderie with members of the community might dominate the show, were it not for Minervini’s patchwork storytelling. Even in a state of vulnerability, Judy speaks with such gravitas that confronting her so intimately is disarming—she tearfully launches into memories of her drug addiction or her fear of bullies at school, her soulful rhetoric and expressive features captured vividly at close range. Which is not to say it’s all pain and bitterness for Minervini. What You Gonna Do When The World’s On Fire? bobs from traumatic recollections to the routine imparting of hard truths, but there are tempering moments of communal bliss and strength, like Judy’s cathartic musical performance or a scene where Ronaldo and Titus take a ride together, their bikes decked out with strings of light.

Minervini isn’t interested in explaining the ins and outs of gentrification or the institutional groundings of racism. Nor does he bother with specifics regarding his subject’s backgrounds, the kind that could require direct interviews. His approach, which might be intrusive or exploitative in the wrong hands, is the product of nurtured relationships; he spent years before production started building trust with his subjects, and ended up shooting over 180 hours of raw footage. In any case, there’s a difference between reveling in or reproducing tragedy and simply listening, with sustained attention, to someone relay their experience living and surviving it. Minervini is not at his most provocative in What You Gonna Do When The World’s On Fire? That’s a good thing.