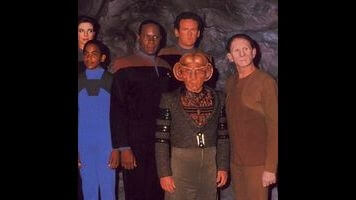

Star Trek: Deep Space Nine: "The Way Of The Warrior"

“The Way Of The Warrior” (season 4, episode 1; originally aired 10/2/1995)

In which the Founders are coming, but the Klingons are here…

As always, checking into a new season means adjusting to a show which is almost, but not quite, exactly like the show you left behind. It’s a bit like getting a new car—serves the same purpose in your life, but golly gee, look at all these nifty features. Like Sisko, sporting a shaved head which, combined with his facial hair, makes him look quite the badass. Kira has a new haircut too, and it’s very cute. (She’s still a badass, naturally.) After last season’s scuffle with the Founders, Sisko has set the crew of Deep Space Nine do regular drills, trying to master the tricky art of finding a Changeling who doesn’t want to be found. Everyone looks a bit shinier, a bit older, a bit more tightly wound—but not to the point of neurosis. There’s just an inescapable sense that, the shit having gotten real, everyone accepts that it’s going to continue to be real in the immediate future. This is one of the more nebulous advantages of ongoing continuity: It helps to set a tone so subtle we’re not always sure it’s there. Obviously Sisko and the others need to be on their guard for the rest of this feature-length episode, because the story needs to remind us that tensions are high. But that unease lingers. I caught myself looking at various characters and wondering if they were who they really said they were, and wondering what their motives might be. That concern will linger, I suspect. Nothing can be taken at face value anymore.

When a situation becomes this unstable, it’s not just personal identities that are at risk. Alliances become strained, and where some see danger, others look for opportunity. The Klingon Empire hasn’t been a danger to the Federation for quite some time; when reintroduced back in Star Trek: The Next Generation, relations with the warlike culture that plagued Kirk and Spock on the original series had finally achieved an uneasy peace. That peace only strengthened over TNG’s run, as each fresh encounter with the Klingons demonstrated how far a once mighty race had fallen, plagued by infighting, bad decisions, and an inability to move beyond the celebration of violence and conquest which had so long defined them. Most of these appearances centered around Worf, the first Klingon officer in Starfleet, an orphan raised by human parents who spent much of his time on the Enterprise struggling to define his idealized version of Klingon life, and the corruption and pettiness he found back on the home world. Not all these stories worked, but the show’s willingness to treat the Klingons as more than just a fallen enemy did it credit.

The few times Klingons have appeared on the station, DS9 has done its best to continue that trend. Without a Klingon in the main ensemble, though, those stories didn’t happen often; besides, between TOS and TNG, it seemed like all the major Klingon epics had already been told. And yet here we are, with the Founders threatening war on all fronts, while the Cardassians and the Romulans fall back to lick their wounds, and the Federation preaches caution. Shouldn’t someone step up, and do what needs to be done? Sisko is cagey as hell, but surely he can’t be expected to save the universe from the Dominion threat entirely on his own. Surely he’d welcome assistance, especially if it came in the form of the entire Klingon fleet.

“The Way Of The Warrior” is a terrific 90 minutes of television, building to its conclusions slowly but without hesitation, using threats the show has spent the last three seasons carefully establishing to shift the main arc in an unexpected direction. Of all the possible danger our heroes might have faced, Klingons would not have been very high on the list. It’s hard to remember the last time the Klingons have come across as dangerous on a Trek series. I don’t mean on an individual basis; there have been plenty of fierce warriors on both TNG and DS9. But as a people? The Romulans were scarier in Picard’s era; Sisko had to face off against first the Cardassians, and then the shapechangers. A bunch of drunken buffoons tossing knives and pining for the old days hardly seem like a terrifying foe. Yet the presence of dozens of Klingon ships floating casually around DS9’s pinions isn’t a joke, and regardless of what the fleet’s leader, General Martok, assures Sisko, they aren’t a comfort. Martok says the Klingons have decided to get involved with the Dominion War. That’s great, but now they’re just hanging around the station, harassing the locals and beating on Garak. Or worse, they’re illegally seizing outgoing ships for unwarranted searches, demanding proof that every transport or freighter leaving the quadrant is Founder-free.

Trek races work best when they can hit two levels at once. The first level, the most straightforward and the one which inspires all that fan passion and cosplay and media tie-ins, is as convincing fiction. We don’t need to know the Klingons down to their DNA (although I wouldn’t be surprised if someone has tried to), but the more we believe they are a distinct species from our own, an alien race with its own identity and history, the more we invest in the stories around them. The second level is more nebulous: The Klingons should be a reflection of some aspect of human behavior. The better the writers are able to use a species to show us a sort of twisted mirror version of ourselves, the more resonant these stories become.

You’ve probably noticed that these two levels are at odds with one another: The more obviously a Trek race is a human surrogate (or, worse, a symbol for a specific emotion or weakness), the less convincing the fiction. Balance works best (and I’d argue that it’s generally better to focus more on getting the first level down before worrying too much about the second), which is one of the reasons this whole Dominion story is so fascinating. Sisko and the others are the “normal” ones, largely because they’re distinct individuals. They don’t represent anyone but themselves. But the Cardassian and Romulan attack on the Founder’s homeworld last season was an example of how one natural reaction to a potential threat is to use it to promote our own myth of control and self-reliance. Tain wasn’t just trying to end the war. He was trying to use it as an excuse to regain his lost glory, to deny the weight of time and the arc of circumstance and make himself a king once more. There’s tragedy in that, for all of Tain’s cruelty, and the tragedy means more than just a grey guy with a bumpy forehead overreaching and paying the price.

The same is true of the Klingon plan. Martok, under the orders of Chancellor Gowron, is keeping secrets from Sisko. The fleet isn’t simply there to offer protection, or even to head off into the Gamma Quadrant to face down the Founders and the Jem’Hadar directly. Instead, they’re using the chaos to launch an assault on Cardassia. The Cardassian government has been recently overthrown by the civilian authority we heard rumbles of last season, and Gowron and his men argue that this revolt is actually a Changeling plot. It’s an assumption which is both somewhat reasonable (it’s hard to put anything past the Founders, really), and also calculated to offer the Klingons the greatest chance for glory possible. The Cardassians and Romulans tried to shortcut a war by attempting a surprise attack with little useful information; the Klingons have decided to exploit that potential war for their own ends, so intent on returning to the old days that they aren’t particularly worried about crossing every “t.” While their plans threaten to destroy the peace treaty they signed with the Federation, and while their attack on Cardassian space leads to the loss of innocent life, the Klingons aren’t exactly the bad guys. Their position is just understandable enough to put them in a gray area; while Gowron and Martok and the rest are overcome by the lust for battle, there’s every chance that they really do believe this is the smartest way to face off against the Dominion. It’s self-serving logic, but it maintains a level of complexity throughout the episode that keeps the action as fascinating as it is intense. The best part? The only changeling to appear in the episode is Odo. (Or so we think.) Just the idea of them is enough to make everyone crazy.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.