If Summer Of ’84 had come out before Stranger Things became a phenomenon, would it have been better received? Maybe. At least then it would have been novel. But the fact is that we are currently late in a cycle of films and TV series—a cycle that not only includes Netflix’s hit, but also last year’s Super Dark Times and IT: Chapter One—all based around the same concept: A group of adolescent outcasts (boys, usually) embarks on a dangerous, horror-tinged adventure in small-town ’80s America. (The ’90s will also do in a pinch.) That cycle is itself heavily indebted to similar stories that actually came out in the ’80s, like The Goonies, The Monster Squad, and Stephen King’s original novel version of IT. And unfortunately, although the film tries to freshen up the formula with true-crime-inflected details, Summer Of ’84 compares unfavorably to all of them.

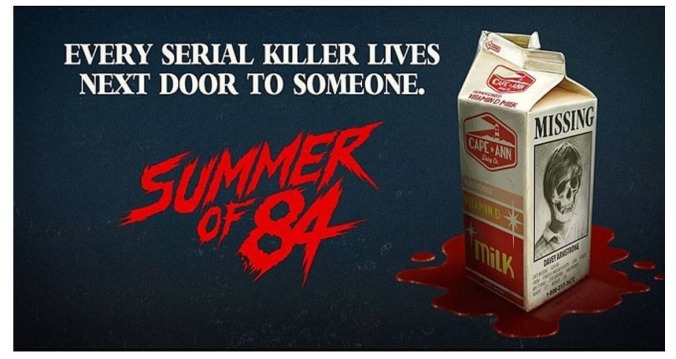

This particular piece of nostalgia-bait comes from French-Canadian filmmaking collective RKSS, which also produced 2015’s Turbo Kid. Where that film aped the style of ’80s direct-to-video action films, this one moves the action to the decade itself. We open in the small town of Ipswich, Oregon, where a serial killer recently dubbed the Cape May Slayer has been kidnapping and brutally murdering young men for months. Fifteen-year- old conspiracy freak Davey Armstrong (Graham Verchere) is obsessed with the case, and he’s convinced himself that Wayne Mackey (Rich Sommer), the genial bachelor cop who lives next door, is the killer. His trio of archetypal friends—moody punk Eats (Judah Lewis), token fat kid Woody (Caleb Emery), and über-nerd Faraday (Cory Gruter-Andrew)—couldn’t care less about the murders, and it’s with much eye-rolling that they join Davey in his quest to prove Mackey is the killer.

For a town ostensibly on lockdown in the midst of a horrifying wave of gruesome crimes, the residents of Ipswich don’t seem very concerned, leaving doors unlocked and kids home alone to play a game called “Manhunt” that involves wandering around in the woods in the middle of the night. “That’s just how it was in the ’80s,” you might say, launching into a diatribe about helicopter parenting. And that’s true. But it’s not the case here: This is just one of many logical inconsistencies that mar the film, distracting from the action and symbolizing a larger lack of attention to detail on the directors’ part. A Nightmare On Elm Street was consistent in never showing the parents; this film makes them overprotective when it’s convenient, and oblivious at other times.

The film’s dialogue and characterization are similarly undercooked: The script strains painfully hard for off-the-cuff vulgarity, but never quite achieves it, and while the pop culture references—always a punching bag for critics when dealing with nostalgia-themed entertainments—are applied sparingly, the tin-earned dialogue gives them an awkward, shoehorned-in quality. Summer Of ’84 never really gives us a reason why these kids should be friends, and although we spent most of the film watching them hang out, the direction is too stiff to call it a proper hangout movie.

The film’s inconsistency and inauthenticity are most clearly expressed in the character of Nikki (Tiera Skovbye), Davey’s ex-babysitter and the only non-parental female character in the film. Nikki’s motivations aren’t as important as the role she plays in the boys’ adventure, first as an unattainable fantasy girl and then as a down-to-earth fantasy girl who’s down to hunt monsters with the boys. The idea that a pretty, popular 17- year-old would have no one to share her problems with besides a kid she used to babysit—and would be romantically attracted to that kid, to boot—is as laughably implausible as it is narratively convenient.

One thing Summer Of ’84 does do well is suspense. The higher the stakes are raised, the more compelling the film gets, and a dramatic shift in tone in the third act leads to pulse-pounding excitement and some genuinely gruesome and shocking images. Even the jump scares and the obligatory synthesizer score are effective, in their own, expected ways. But, given that this film is 106 minutes long and doesn’t really pick up until its last half hour, by then it’s far too late.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.