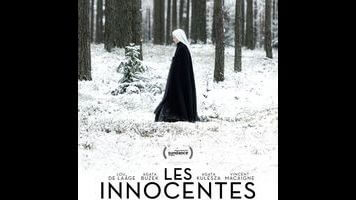

Part of the problem is its choice to focus largely on a character who, though based on a heroic real-life individual, doesn’t really have much to offer in the way of drama. Mathilde Beaulieu (the real woman’s name was Madeleine Pauliac), a young doctor working with the French Red Cross, is still tending to wounded soldiers in Poland, six months after the end of World War II. One day, a nun from a nearby convent shows up to beg for her help, without explanation. The sight that greets Mathilde when she arrives is surreal: a hugely pregnant nun, dressed in her habit and writhing in pain. Only after delivering the baby does Mathilde learn that Russian soldiers had invaded the convent near the end of the war and raped all of the nuns, repeatedly. At least seven others are also pregnant, and while the mother superior (Agata Kulesza, who memorably played opposite a nun in Ida) is willing to let Mathilde provide necessary care, she’s also determined to avoid the shame that would result should news of what happened get out.

Lou De Laâge, who fairly ignited the screen in Mélanie Laurent’s Breathe last year, gives an expertly composed performance as Mathilde, but she can’t quite hide the role’s fundamental hollowness. Apart from initially telling the first nun who seeks her out to find someone Polish to help, Mathilde is never less than resourceful, professional, and deeply empathetic; mostly, she serves as a handy sounding board for various nuns who confess their doubts and misgivings. The Innocents wants to ask whether and how it’s possible to go on believing in God after being not just violated but, in a sense, mocked (by the permanent evidence of lost chastity that a baby entails). Screenwriters Sabrina B. Karine and Alice Vial never quite manage to articulate that question in a compelling way, however, and director Anne Fontaine, whose previous films are mostly either trifles (Gemma Bovery, Coco Before Chanel) or outright ridiculous (Nathalie…, Adore), isn’t up to the challenge of visually representing an inner void. Consequently, while the film is consistently absorbing, and occasionally quite moving, it has the slightly stodgy feel of retroactive journalism. There’s some value in learning about a heretofore underpublicized wartime atrocity. Watching tentative, lackluster efforts to plumb the depths of the human soul, however, is an exercise in frustration.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.