Players like George Washington Benson are uncommon. Born in Pittsburgh and raised in the city’s Hill District, he used to pick a ukulele on street corners at four years old, making a few bucks here and there until he turned eight and got a real gig working in an unlicensed nightclub on weekends. The cops shut the place down fast and Benson started making recordings. He was something of a child prodigy, one might say—like Mary Lou Williams, who used to play piano for the Mellon family. RCA Victor in New York got a jump on Benson, tracking his singles “She Makes Me Mad” and “It Should Have Been Me” in the early fifties. Leroy Kirkland from Groove Records oversaw the production. There are discrepancies over what name Benson sang his songs under then. The vinyl label said “George Benson.” A U.S. jazz and blues compendium reported that he performed for RCA under the name “Little Georgie.”

Benson stayed in the Hill District for a while, attending Connelley Vocational High over on Bedford Avenue. He dropped out eventually, in pursuit of a music career. He’d learned how to play instrumental jazz music and worked under the stewardship of an organist named Jack McDuff, but Benson dreamt of playing like Hank Garland. Turns out he was something else—something greater—entirely. In his early twenties, Benson started leading bands of his own. He recorded The New Boss Guitar of George Benson for Prestige Records in ‘64, It’s Uptown in ‘66, and, with Lonnie Smith on the organ and Ronnie Cuber puffing the baritone sax, The George Benson Cookbook in ‘67, both for Columbia. By ‘68, Benson was playing guitar on Miles Davis’ “Paraphernalia,” which I reckon is still the best track on his Miles in the Sky LP. Benson eventually ditched Columbia for Verve.

He hopped around labels a lot in his career, putting out the terrific The Other Side of Abbey Road on A&M in 1970 before signing with CTI Records, Creed Taylor’s spanking new jazz fusion imprint. Taylor had worked as a producer at Verve, putting players like Stan Getz on to bossa nova and Brazilian music. One of his big hits at CTI was Prelude, a breakthrough record of conga-flavored, Latin-orchestra jazz music that took Deodato out of the arranger-for-hire biz and threw him into temporary stardom. Prelude was CTI’s big money-maker, while Benson spent his time with the label guesting on other people’s projects—like Freddie Hubbard’s First Light and Sky Dive and Stanley Turrentine’s Sugar, which won the Best Jazz Performance by a Group Grammy award in ‘73. Benson liked reinterpreting rock and roll. He reimagined the Beatles final record and covered the Great Society and Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit.” Bad Benson was a #1 hit on Billboard’s jazz chart, and Good King Bad and Benson & Farrell sold well, too.

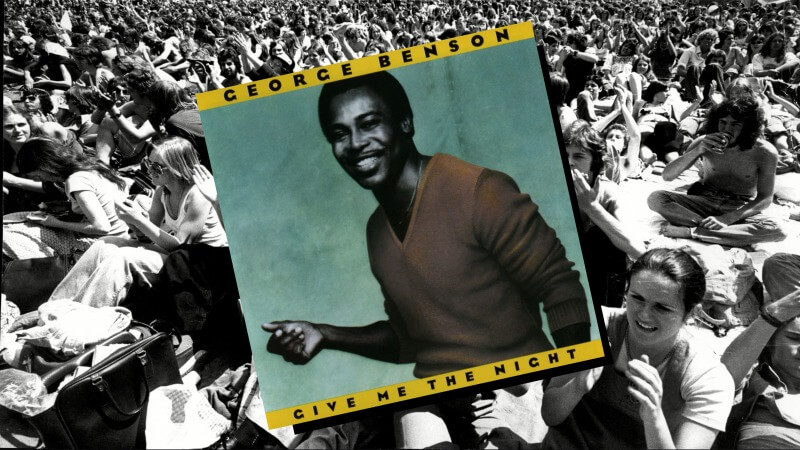

For five years, between 1976 and 1980, George Benson was a star. His record Breezin’ became a massive critical and commercial success, selling a few million copies worldwide, topping the Billboard 200, and earning him five Grammy nominations. Christgau called the album “mush” and gave it a C grade, but Christgau didn’t know his ass from a hole in the wall half the time. Breezin’ was irresistible—the makings of a jazz-funk great embracing the temptation of mass-market appeal. Benson stepped off his instrumental soapbox and made the language of Leon Russell’s “This Masquerade” into his own, draped in Jorge Dalto’s acoustic piano solo. He took José Feliciano and Bobby Womack’s fast-fingered phrasings and plugged them into his own fluid guitar moves. The whole record sounds invincible, seductive. The same year Breezin’ put his name on a marquee, Benson toured with an ailing Minnie Riperton and was invited to sing backup on Stevie Wonder’s “Another Star,” the loose, Latin-infused delight that finishes Songs in the Key of Life. He recorded the Muhammad Ali biopic theme song, “The Greatest Love of All,” which Whitney Houston would later make even more famous, and spent time in the studio with Claus Orgerman. He covered “On Broadway” on his Weekend in L.A. live tape and it became a Top 10-charting, adult contemporary staple and snatched a Grammy award for Best R&B Vocal Performance.

Eventually, Benson wound up in the company of Quincy Jones and his Qwest label start-up. Jones was on a hot streak not unlike Benson’s at the time—the producer’s recent CV included Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall, Rufus/Chaka Khan’s Masterjam, and the Brothers Johnson’s Light Up the Night in a 9-month period. Upon meeting Benson, Jones had just one question for the guitarist: “Do you want to make the world’s greatest jazz record, or go for the throat?” Benson’s answer was easy, and Jones brought Heatwave songwriter Rod Temperton and engineer Bruce Swedien in to accommodate. Benson requested the Off the Wall players help make his next record and they showed up: Herbie Hancock and Greg Phillinganes on piano; Richard Tee, Clare Fischer, Michael Boddicker, and George Duke on synth; Lee Ritenour on guitar; Louis Johnson and Abe Laboriel on bass; Carlos Vega, John Robinson, and Paulinho Da Costa on percussion; Jerry Hey on trumpet; Kim Hutchcroft and Larry Williams on sax and flute; Patti Austin, Jim Gilstrap, Diva Gray, Jocelyn Allen, and Patrice Rushen singing backup vox. Everyone convened at Cherokee Studios in Hollywood and then Kendun Recorders across the freeway in Burbank.

After a month in the studio, Benson was ready to pack up and head east. But Jones called Benson, letting him know they had more song to finish. Benson wasn’t easily convinced. “Man, it’s a good song,” Jones doubled down. “It won’t take long.” They tracked “Give Me the Night” in a day. Jones heard Benson’s middle-passage guitar part and decided to put it all over the track, especially during the intro. It was the hook to end all hooks; swagger cut with sweetness. But fatigue was in full effect, causing Benson to struggle with the vocal. He sang in a “crazy, affected voice,” and Austin compared it to hearing the string arrangement against James Brown’s “sandpaper vocals” on “It’s a Man’s Man’s Man’s World” for the first time. Benson begged Jones not to use the take and Jones promised he wouldn’t. But when a test pressing landed in his hands, Benson discovered that Jones had gone back on his word—building a jazz-funk, post-disco masterpiece out of the guitarist’s supposed missteps. Jones and Temperton went out clubbing every night they worked on Give Me the Night. “Everyone thought they were just being playboys,” Austin recalled to The Guardian. “But they were doing research, listening to tempos.” The single captures their immersion—in Swedien’s synth construction and Jones’ persistent tweaks, in contrasts of dried-up verses and blown-open choruses.

Benson and Jones were not harmonious collaborators, according to Austin (“it was a clash of the titans at first”), but, from my vantage, there are no blemishes on Give Me the Night—only phenomenal success. The album drifts, both through minimalist pop animations and marvelously above them. Nowhere is Benson’s guitar a top-billed star like on his previous full-lengths. The fills are spacious accents, not overpowering bursts. On Temperton’s “Off Broadway”—a superb, instrumental successor to “On Broadway”—the reflection and reverb in Benson’s solo come from a touch of Swedien’s patented “acusonic recording process,” in which he tracked sources separately in stereo pairs rather than close mono mics. Benson’s vocalese and Austin’s luxurious accompaniment express with sentimental color during “Moody’s Mood”; Benson’s scatting on “Dinorah, Dinorah” is flanked by attractive bass lines and a guitar that echoes like sonar. The pop wattage brightens on “Love X Love,” when ghost snares and a deeply embedded groove tango with blustering horn effervescence and whip-smart vocal tapestries. The prismatic “Give Me the Night” ricochets between tradition and invention.

But it’s Give Me the Night‘s final moments that confirm its everlastingness. “Midnight Love Affair” and “Turn Out the Lamplight” are acrimonious slow jams with full-bodied timbres and sustains of mellow, romantic platitudes: “Though the years may make me old and gray, darling, you still take my breath away,” Benson sings, as his and Ritenour’s guitars talk to each other in cursive provocations. It’s all so heady but never overwhelmingly or distractingly dense—lavish and classic before late-period, guitar-driven disco turned into drum machine-obsessed, turntable-spinning house music. The switched-on “Star of a Story” gets a sugar-rush when backdrop vocals are threaded into the circuitry of a pocket synthesizer. Lovemaking rhythms and pastoral strings add a dollop of drama to Benson’s zaps of squiggly, staccato guitar during “What’s On Your Mind.” Give Me the Night is a period piece that’s firmly 1980—a portal connecting the abundance of disco, funk, and jazz in one decade to the sleeker, sparser dance-pop and mainstream R&B from another.

Give Me the Night is my favorite Quincy Jones production. I like it more than Thriller, and it goes ten rounds with Off the Wall and Masterjam. Part of the album’s starpower comes from Temperton’s writing (he elevated two of Michael Jackson’s best-ever singles, “Rock With You” and “Off the Wall,” after all), but Jones unlocked something significant in George Benson in that Valley studio 45 years ago, elevating the guitarist from a dependable jazz everyman to this terrific pop bonafide through the nurturing wisdom of singers they both admired: Nat King Cole, Ray Charles, Donny Hathaway. The ideas on the table were never too brazen; Jones and Swedien’s production never too chintzy. Benson went for the throat, and Give Me the Night became his pièce de résistance—musical heft brought to life not just by an otherworldly set of jingle singers, chainsmokers, dandies, and jazz masters, but by stubborn conductors who disagreed though never catastrophically enough to deform the album’s brilliance. He made commonplace seem one of one. Give Me the Night sounds like oxygen.

Matt Mitchell is Paste‘s editor, reporting from their home in Los Angeles.

******

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.