Video games have spent the last 50 years covering increasingly wide swathes of the human experience. Laughter, tears, an increasingly industry-dominating obsession with horniness… If people can feel it, games are getting better at expressing, exploring, and, critically, inducing it. So where does irritation—genuine, teeth-gritting annoyance—fit in to those lofty goals?

This question is brought to you courtesy of inkle’s new mystery game TR-49, a game that is, like many of the titles created by designer Jon Ingold—Heaven’s Vault, Overboard, Expelled—exactly and precisely my jam… on paper. Don’t get me wrong: The parts of TR-49 that are bait for me—its fascination with both fiction and meta-fiction, its unique player interface, its obvious debt to “database puzzler/narrative deduction” games like The Roottrees Are Dead and especially last year’s exceptional Type Help—work extremely well for me, to the point that I solved the whole thing in a hefty six-hour session of textual indulgence.

But inkle has also always designed its game to the dictates of its own muse, with a focus on immersion and verisimilitude that are cool in theory, but often impediments for me personally in getting to the delicious meat of the puzzles I’m actually there to play with. TR-49 is by no means the worst offender on that score—that, to my mind, would be Heaven’s Vault, a game that often felt obstinately proud of how long, and how elaborately, it could keep me from the rich experience of deciphering an alien language at its core. But the new game’s early going, and its willingness to employ irritation—both deliberately and not—in its gameplay, meant that my first few hours with it were a serious struggle to meet the game on its own terms before I got to the parts I could fall in love with.

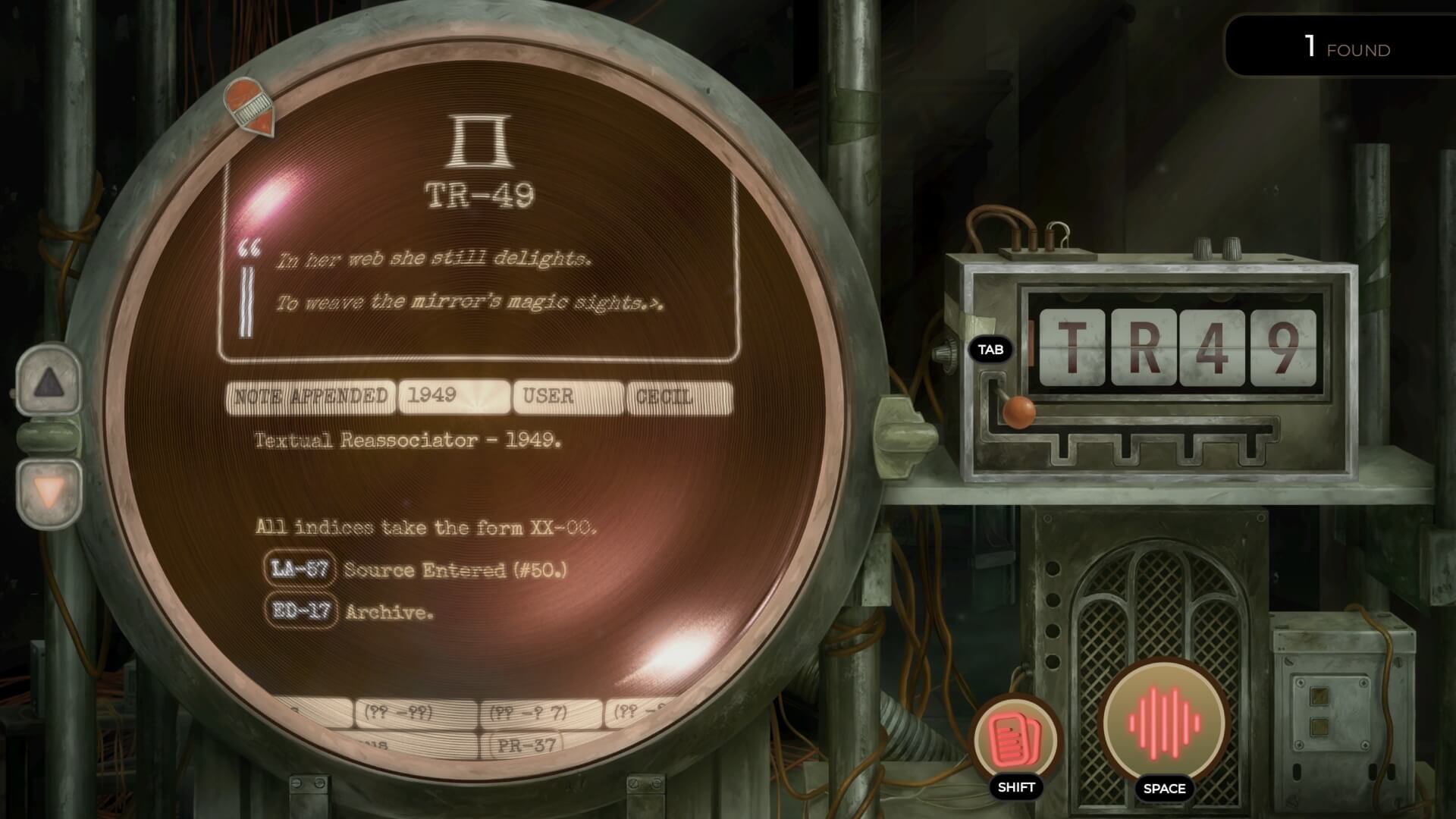

The issues start early. Without engaging in spoilers, TR-49 drops players into the unseen shoes of Abbi, a young woman who wakes up in a basement with two things: An enigmatic machine of vast mystery and unclear purpose lurking in front of her, and a voice named Liam rattling around on her radio. As it happens, I’m a real sucker for enigmatic machines of vast mystery and unclear purpose, but a lot less hot on the topic of listening to video game NPCs natter at me while I’m working away at an interesting problem. (You can skip some of the dialogue by just ignoring the radio, but the game’s writing assumes you’re talking back to Liam with some regularity.) So one of the first things I did after booting up the game is something that’s probably anathema to a title that bills itself as “narrative deduction meets audio drama”: I went into the options and turned the game’s voice volume down to 0, and never turned it back up.

This is meant with no disrespect to voice actors Rebekah McLoughlin and Paul Warren, who I’m sure give wonderful performances throughout the game, as it unspools its story of a bizarre code-breaking machine that’s now being used as a sort of prototype digital library, and being sought after by shadily menacing figures. But the insistence of the game’s dialogue—your radio chirps constantly as the game begins, requiring a button press to answer, and continues to pop in as you unlock new entries in the machine as a perverse form of reward—really couldn’t have run harder counter to what I wanted to be doing while playing: Reading and thinking. Which I was doing a ton of, because, seriously, TR-49 is a genuinely lovely contributor to the growing narrative deduction genre. (Even if I can’t help but note again just how much it owes to William Rous’ Type Help, as both games have a similar conceit of working out the naming conventions of a very unorthodox filing system, and then using them to extrapolate the names of other files, as their primary gameplay hook.) Then, late in the game, inkle starts deliberately using the radio to make these basic acts of cogitation more difficult. Which, again, is the sort of thing you have to begrudgingly acknowledge as clever—the player’s focus and attention are the primary resources they’re utilizing in a game like this, so finding ways to tax them is interesting play design, as well as a strong tool for characterization—while not actually, y’know, wanting that thing to be happening.

This commitment to annoyance as a primary way to guide players’ behavior isn’t confined to the ears, either. TR-49 also has a clever way of encouraging players not to just guess at unknown file names when searching for new documents as they slowly decipher its multi-decade, highly literate mystery: A sufficient number of mistakes will begin garbling the game’s text on a letter-by-letter basis, making it increasingly difficult to decipher anything. (Correctly inputting guesses seems to alleviate the problem, although I’ll admit this is only guesswork formed in the heat of just trying to get the fucking words to settle down.) And, again—given that reading and understanding words essentially is the game inkle has created here—discouraging unwanted behavior by attacking that basic process makes sense. It’s just also extremely irritating.

If it feels like I’m spending all my time here reporting on a race by describing the hurdles, instead of the sensation of actually running the damn thing, well, yes: One of the things about irritation is that it’s extremely good at sticking in the memory. (Not to beat a dead horse, but I can only remember bits and pieces of the plot of Heaven’s Vault several years on, but the sensation of being hectored constantly by that goddamn robot to leave locations I knew I’d never be allowed to visit again is seared into my soul.) Even so, I want to be clear that I eventually found my way down the path to enjoying TR-49 immensely. (It’s certainly my favorite of inkle’s games: Tightly contained, beautifully written, and with a lovely sense of aesthetics as you pull levers, move dials, and peer at flickering monitors.) Notably, the game gets better as it goes along, with several moments of dark epiphany, and endings that do the clever trick of asking you to demonstrate that what you’ve just played—that is, read and thought about—has stuck with you enough to understand how the system you’re now intimately familiar with can effectively be changed. There’s a great story here (and probably also some great voice acting, if you’re the kind of person who can handle voices in their ears while they’re trying to focus on more interesting problems). The irritations are part of the texture of that, and I can appreciate that the game wouldn’t be the same without them.

I just don’t have to like the dang things.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.