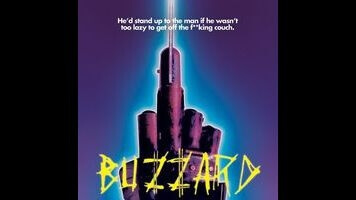

The classic American underground film may seem extinct, but every year or two, as though through some fluke of recessive creative genes, one pops up in the indie landscape. Buzzard is one of these freaks of nature. Aggressively lower-middle-class, Joel Potrykus’ black comedy tackles loserdom as though it were an existential condition. It’s a movie of nervous cringes and subterranean themes, animated by the antiheroic exploits of a paranoid, Freddy Krueger-obsessed small-time grifter named Marty Jackitansky (Joshua Burge, remarkable). Set in Michigan in what appears to be the early-to-mid 2000s, Buzzard tracks Marty as he dissolves into pure, psychotic survival instinct—a downward arc that would probably seem extreme if it weren’t digging so deep into the dead-end, just-over-minimum-wage psyche. Think Vampire’s Kiss on a DIY scale, with motels and basement rec rooms in place of brownstones and nightclubs and a bladed Power Glove in place of plastic fangs. That’s Buzzard in a nutshell.

An archetypal slacker with long greasy hair, Marty scams refund policies and promotional giveaways for cash and coupons. One day, he gets the idea that he’s about to get busted for stealing a stack of undelivered checks from the mortgage office where he temps, and goes on the lam, first holing up in his friend’s basement “party zone” (complete with CD towers, toaster oven, and Matrix Reloaded poster), and then hightailing it to Detroit. Of course, no one is really looking for him, just as no one notices that he doesn’t actually do anything at his job. In this mind-numbing Midwestern dead zone of bank branches, convenience stores, and “No Personal Checks” signs, the only people who care enough to notice Marty are other swindlers—a register-skimming clerk here, a payday loan store owner there.

That might be enough to make Marty into a pathetic figure, but what makes him captivating (and consistently funny) is Burge’s performance. Marty is arguably the laziest and dimmest swindler in film history, but he’s also riddled with anxieties—an outsider, prone to identifying with horror movie monsters, who’s constantly being undermined by his own paranoia and lack of planning. He’s the sort of criminal mastermind who goes through the trouble of copying a motel room key to sneak back in later, only to oversleep and get caught by room service without a backup plan. But there’s something pure bottled up inside of him, which bursts through in a scene where he eats an entire plate of spaghetti, chomping away with a look of absolute satisfaction that brings to mind Malcolm McDowell being fed at the end of A Clockwork Orange. (Not coincidentally, one of Potrykus’ earliest shorts was called The Ludivico Treatment.)

Shot in itchy long takes at some of the ugliest locations America has to offer, Buzzard is outwardly confrontational; it follows its aloof antihero from one awkward situation to another, slowly inching from cringe comedy into psychological rot, and even introducing an element of queasy body horror in the form of a festering cut on Marty’s hand. And yet it’s also sympathetic and sincere—a movie that genuinely feels like it’s trying to wrestle with what it means to feel like a nobody living nowhere special, and to want to be a monster, running through the night, claws out.

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)