Audra McDonald is a living legend of the American theater, with more Tony Awards than any other performer (six) and the distinction of being the only person to win all four acting categories for leading and featured roles in both musicals and plays. She’s done work in television and film, most recently in last year’s underappreciated family drama Ricki And The Flash, but the stage is her home, and she’s at her best when she’s performing live.

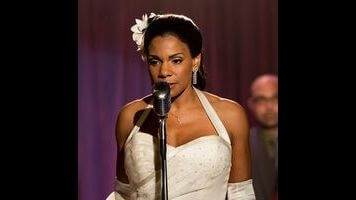

McDonald took home her most recent Tony Award for her performance as Billie Holiday in Lanie Robertson’s Lady Day At Emerson’s Bar & Grill, a play with music set four months before Holiday’s death detailing a loopy, nostalgic evening at an imaginary Philadelphia jazz club. It’s a flawed script that plays like a dramatized Wikipedia summary at times, but the opportunity to see a master vocalist and dramatic actress like McDonald channel a jazz icon is a highly attractive one, which is why HBO has reunited McDonald and her Lady Day Broadway director Lonny Price to film the production.

The stage has been relocated from Manhattan’s Circle In The Square Theatre to New Orleans’ Cafe Brasil, but the filmed version maintains an intimate setting, allowing McDonald to saunter into the audience and interact with patrons at elevating levels of inebriation throughout the evening. The camerawork intensifies that intimacy, accentuating the smallness of the space by capturing it from multiple angles while offering close-ups that bring the viewer deep into the action. Especially toward the end, there are some striking extreme close-ups of McDonald’s face overcome with drug-amplified feeling as she sings songs like “Strange Fruit” and “Deep Song,” and the grueling work that goes into performance shows in every bead of sweat and every exquisitely timed tear.

Price and director of photography Richard Siegel do their best work when they show restraint, minimizing the number of cuts and lingering on shots to help sustain the momentum that drives strong stage acting. This restraint is especially important when Holiday stops singing and starts recounting her past with hefty chunks of background information, and cutting to different shots of McDonald in the middle of these stories interrupts the rhythm of her performance.

When she’s singing, McDonald slips into Holiday’s persona the second the music begins, and she can sustain that illusion from every camera angle for any duration because her vocals are so evocative of Holiday’s singular sound. That illusion takes a little more work to maintain once the music stops; Robertson’s overstuffed script sacrifices a natural sound to fit in all the biographical material, and McDonald struggles to bring spontaneity to the myriad monologues when they become overly expository. When she succeeds, these anecdotes about the past play like casual stage banter, but more often than not, she gets weighed down by a script that clumsily tries to cram Holiday’s entire history into a 90-minute show.

The monologues are informative and provide valuable context regarding Holiday’s troubled upbringing and the various ways her life has been impacted by a racist society, but Robertson puts little effort into fitting these topics gracefully into Holiday’s on-stage repartee. The script ends up being McDonald’s main obstacle to creating a believable Billie Holiday, and the camera doesn’t help her when it moves positions. McDonald’s performance is being filmed, but it’s still modulated for a live crowd of audience members that watch the show from specific seated locations. The best monologues are the ones where the camera tries to replicate this viewing experience with fewer cuts and longer takes, and while that doesn’t wash away the script’s weaknesses, it amplifies the power of McDonald’s performance to compensate.

Starting with copious amounts of booze before taking a late break to shoot heroin backstage, Holiday undergoes a severe transformation over the course of the play, and McDonald does remarkable work showing that degradation during the smaller moments between songs and stories. The transitions into the former are much smoother than the latter, and there’s an element of routine in her performance of the music that makes these tunes Holiday’s main tether to lucidity because she’s done them so often and knows them in her soul. Conversely, the monologues are sudden, increasingly jarring bursts of composure that come and go depending on when the playwright wants to jump back into the past.

By the end of the play, Holiday is so high and worn out that McDonald can really get rough and sloppy with her line delivery, and that extra texture is what the rest of the script needs. McDonald still reaches a place of real pain and despair, though, and the tragedy of Lady Day At Emerson’s Bar & Grill is seeing the bright firecracker from the start of the play fade into the dark place within herself. It’s a change that comes through clearly in McDonald’s body and voice, and despite the faults of the text, the central performance provides a heartbreaking, multifaceted portrayal of a black female artist yearning for respect, haunted by past mistakes, and tormented by addiction.