When Angel’s Egg was released in 1985, many didn’t know what to make of it. It was an experimental, lyrical, and cryptic art film that confounded audiences with opaque storytelling, something that contrasted heavily with the crush of mecha anime and well-known IP that came out alongside it.

While its director, Mamoru Oshii, would eventually go on to helm classics like Ghost in the Shell and Patlabor, he has spoken quite openly about how the film was disastrous for his career in the short term. The movie’s straight-to-video, Japan-only release (with limited theatrical screenings) flopped according to Oshii, and in a 2014 TIFF interview, he said, “After I made that, no one gave me jobs for three years.” He recently described the film as “a pitiful daughter that I couldn’t properly introduce to the world.”

However, despite being met with indifference by general audiences in 1985, the film has gained gravitas and acclaim in the years since, eventually earning a well-deserved spot as a cult-classic. For its 40th anniversary, GKIDS acquired licensing rights to the movie, which led to a 4K screening at Cannes, a limited theatrical run in North America last week (its first theatrical release in the States), and the news that the film is finally coming to streaming within the coming months.

But why is it that this brief 71-minute flick has continued to enrapture and beguile, ensnaring countless viewers in its dark fantasy daydream decades later? The most straightforward answer is how it uses sumptuous visuals to deliver a monochrome gothic world of sights that excite the imagination. Its imagery is bizarre and naturally invites curiosity: pulsing organic tanks, abandoned cobblestone street corners, a floating mechanical eye emerging from bubbling sea foam. Some have described it reductively as “what would happen if Tarkovsky directed an anime,” and while that isn’t quite right, it does share a penchant for patient camerawork and dense imagery that very much feels like “sculpting in time.”

But more than just being strange, there is an inescapable sense of a deeper meaning just at the periphery, that all its symbols and motifs can be neatly arranged, clicking together with a satisfying snap that definitively “solves” its mysteries. If we just dig a little deeper, all these questions will be answered cleanly and for all time, right? Of course, that’s a bit misguided. It is fundamentally incorrect to assume there’s a “definitive” read to any work, and that’s only more true with a film as hallucinatory and evasive as this one.

However, while there isn’t one “right” way to interpret Angel’s Egg, there are still interpretations supported by much of the text—again, much of the movie’s enduring appeal is that its striking sights invite these sorts of educated guesses.

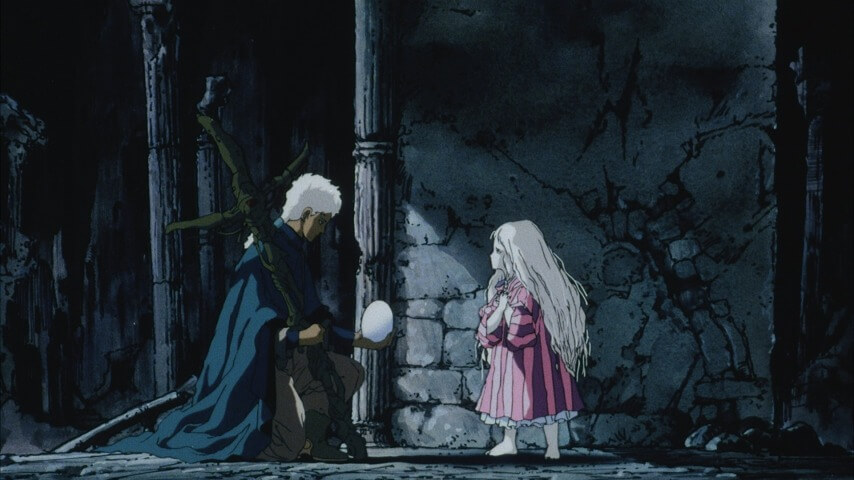

For those who’ve never seen the film, there isn’t much explicit plotting to detail: it follows an unnamed pair, a small girl in a pink nightgown, and a young man bearing a cross-like device, as the girl desperately attempts to protect an egg in an abandoned gothic city. They roam desolate streets as faceless fishermen hunt shadows, and a heavy rain causes a flood. There are only a handful of lines of dialogue, and the animation is presented in a languid style with minimal cuts.

As for the most apparent throughline of its symbolism, it’s right there in the name: Angel’s Egg. The story is full of Christian imagery, a likely byproduct of Oshii’s self-described philosophical interest in the Bible. The egg the girl painstakingly cares for throughout is implied to have been laid by what she calls a “bird,” but we eventually see the fossilized remains of the creature she’s referring to, a humanoid skeleton with inexplicable wings—an “angel.” As for the man, he carries a metallic object (maybe a gun or weapon of some sort?) in the shape of a cross over his shoulder as if he’s a penitent. Both of his hands are bandaged with cloth covering his palms: the bandages are exactly where stigmata would be located, which, for those who skipped Bible Study, are the wounds corresponding to where Christ was crucified.

While many have assumed these symbols are meant as visual flavor to evoke a general sense of grandiosity and religiosity instead of referring to anything specific, there’s a pivotal Biblical allusion that centers these images: direct mentions of Noah’s Ark. Specifically, as it begins to rain, the man paraphrases several passages from the Book of Genesis, starting with Genesis 6:7, which recounts the start of the flood that would wipe all life on the planet: “And the Lord said, I will destroy man whom I have created from the face of the earth; both man, and beast, and the creeping thing, and the fowls of the air; for it repenteth me that I have made them,” the original passage reads.

He then recounts much of the rest of this flood as described in the Bible, again paraphrased but fairly one to one, until diverging after Genesis 8:11, where Noah releases a dove to test if the world remains flooded. In the original story, the dove returns with an olive leaf, signifying that the flooding is subsiding. By contrast, in the man’s telling, the dove never returns, and the people of the ark waited so long that they eventually grew tired of waiting.

“They forgot they had released the bird, even forgot there was a bird and a world sunken under water,” he says. He goes on that they forgot where they came from “so long ago” that the animals have since turned to stone (the fossils we see throughout the film). He then speculates that this story may have all been a dream, or that he, the girl, and the illusory fish “only exist in the memory of a person who is gone,” or that no one really exists, or that the bird was never real.

In many ways, this speech stands out. It is by several orders of magnitude the longest stretch of sustained dialogue in the movie, so much so that it takes up about half of its tiny script (which is under 700 spoken words total). However, more than this, it’s arguably the most direct reveal of what the film is “about,” portraying a world that has forgotten its past and lacks the context of a larger picture.

Its characters pantomime behaviors of a history that they don’t understand without meaning: the man with his cross and stigmata pays penance for sins he doesn’t remember, while the girl indefinitely protects an egg of dubious divinity, imagining that the creature will finally spread its wings (which it won’t).

And then comes the big “aha” moment at the very end: the camera slowly pans out to reveal that the city where the story takes place is located on an island that is actually the underside of a massive vessel, presumably Noah’s Ark. It appears that in this version of the story, the flood never abated, with these people ultimately being abandoned by their god.

At first, it’s quite difficult to connect what this has to do with everything else in the film, but many of the pieces fall into place when considering another allusion to a longstanding tale: Plato’s allegory of the cave. Earlier, as the girl wanders, we see what initially appear to be bronzed statues of fishermen throughout the city, only for these forms to suddenly spring into action when the shadow of a fish appears. The faceless anglers march through the streets, launching spears at the phantom as it “swims” along the outer walls of the village’s buildings. Their projectiles meet the fish, but instead of killing it, these weapons pierce homes and shatter windows while the shadow swims on, unaffected. The girl directly remarks that the fish isn’t real.

It’s a direct parallel to the allegory of the cave, where shackled prisoners watch shadows projected on a cave wall. Lacking the context of a broader world, these people assume that the shadows are “reality” instead of projections caused by people passing through the cave with torches. It’s only after exiting the cave that the prisoners realize these shadows aren’t “the real thing,” but are only the outlines of actual people. Plato’s message in the story was that those who search for knowledge and deeper truths are like prisoners who escape the cave, finally able to see a reality that was initially obfuscated.

Where this all ties together is that all of the characters in Angel’s Egg, whether it’s the fishermen, the girl, or the man, lack any semblance of context. Both the girl and the man admit they don’t remember where they come from or their greater purpose, while the fishermen very literally chase shadows. The girl and the man both carry symbols of religion, but bear none of their original context because their world lost its past along with the flood. Their view of reality is incomplete. It’s no mistake that the fundamental emotion this film evokes is one of confusion and missing context: it is crafted to create the feeling of being a prisoner in the cave, where we’re unable to ascertain the full picture.

This focus on knowledge also ties into another allusion to Christian symbolism, the Tree Of Life. After seeing a detailed inscription on a wall, the man recalls a memory of a massive tree that held an egg. In the Bible, after Adam and Eve gain the sin of knowledge, they’re cast out from Eden, which is where the Tree Of Life is located; here, gaining knowledge means being separated from the bird and its egg.

In one interpretation, the film can be seen as a grim admission of epistemology’s limits. Try as we might to understand the world (and this movie), there are certain truths that will always remain out of grasp, elusive and impossible to prove definitively. Again, the man says as much after telling the story of Noah’s ark, saying that this tale may all be made up and that he and the girl may be a memory, alluding to how everything they see may be nothing more than shadows.

However, a slightly more “positive” read on the situation is that the story of the girl, the man, and the egg is a plea to face reality. Throughout, the girl has an obsessive relationship with the egg, having cared for it for an unfathomable amount of time, as implied by the countless water jugs she collects each day that line the massive structure she lives inside. She guards it day and night, tucking it inside her dress as she scavenges in the abandoned village. After meeting the man, she treats him suspiciously and only seems to trust him after she asks him not to destroy it. She claims to hear sounds of a “bird flapping its wings” inside the egg, which the man says is “just the wind.” And then, what we’ve been waiting for finally happens: as the girl sleeps, the man shatters this egg and the illusion alongside it.

On its face, it seems a cruel betrayal where the man destroys the only thing that has been keeping the girl company, something that was her sole hope in a desolate world. However, at the same time, when the egg is finally shattered, we see that it was empty. “You have to break an egg if you want to know what’s inside,” the man said earlier. The egg was a false hope, a shadow, and by destroying it, the man is forcing her to face the reality of what’s inside (nothing). He’s forcing her to leave the cave. When she chases after him, she falls into a chasm, and an older version of her appears—she was forced to grow up.

Of course, this is all only one interpretation of the picture, with numerous symbols and scenes suggesting other readings of what it all represents—I elided the fact that as the girl falls into the chasm, she switches places with a reflection (another shadow?) and is replaced by dozens of eggs, which doesn’t cleanly fit into the previous explanation. There is an inherently cryptic element at play with the film, born out of the work’s fundamental desire to obscure and deny us full knowledge. Much like how leaving the cave behind for good and finding every bit of unvarnished Platonic “truth” that exists may not be possible, finding an “objective answer” to Angel’s Egg might be similarly quixotic. But still, that doesn’t mean we can’t inch a bit closer to the light.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.