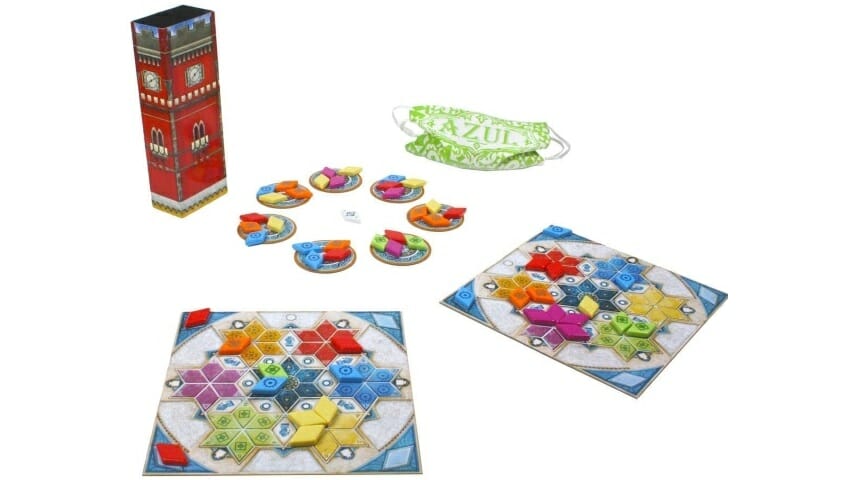

There are six colors of tiles in the game, and in each of the six rounds one of the colors is wild. As in the first two Azul games, four tiles are placed on every factory space (two spaces per player, plus one) at the start of every round, and on their turn a player may take all tiles of one color from one space—plus one wild tile, if there’s one there. Remaining tiles are pushed to the center, from where eventually someone must take some tiles, incurring a penalty of one point per tile taken. (You have to take all the tiles of one color whenever you take tiles.) The first player to take tiles from the center does get to be the start player in the next round, which is a pretty significant advantage—you want to be the start player at least once or twice in the game, depending on the player count.

On each space on the board there’s a number from one to six; to place a tile on a space, you must have that number of tiles of that color, placing one on the board and discarding the rest. It’ll take 21 tiles in total to fill in all six spots on any star, although some of them can be wild cards. One key difference from the previous two Azul titles, however, is that you get to gather tiles over the course of an entire round before placing them, as opposed to placing tiles as you take them. Taking tiles is phase one, placing them is phase two, and the order of placement matters in that second phase because there are tile bonuses available—when you surround certain areas on your board, you get to take one, two, or three free tiles from the central display. You can even store up to four tiles from one round to the next.

All of that means Azul: Summer Pavilion asks you to think about several different strategic considerations over the course of the game. Each time you take tiles, you’re thinking about which ones make the most sense for you to take given what you’ve already placed, but also what tiles your opponents might take, what tiles you might be able to get next time around, and whether you might force an opponent to take tiles from the center. When you place tiles, you’re also deciding between short- and long-term goals on your board; completing those bonuses for free tiles can prove extremely powerful, especially since you can take any wild tiles that are there … but if you don’t complete two of your seven stars, you’re probably not going to win.

Through several plays with two, three, or four people, I’ve found that you can finish two of the seven stars, and maybe, with a little luck, get one of the additional point bonuses for finishing all of the 1/2/3/4 spaces, but that’s the maximum, and it’s easy to get caught unable to finish a second star because of the random tile draws each round. That makes the game feel like it’s over a round too soon, especially since in a three to four player game there will just about always be someone who was victimized by bad tile draws at the end and couldn’t complete a second star.

Azul: Summer Pavilion gives you something familiar in the tile selection mechanic, but how the game plays out after that diverges quite a bit from the two preceding titles. The penalties for taking the first tile from the center are much less punitive. The game has a fixed number of rounds, unlike the original title, where the game ends whenever the first player completes a five-tile row on their board. The scoring here is far more straightforward than in Stained Glass of Sintra, and it’s extremely unlikely that you’ll end up with tiles you can’t use, especially with the ability to store tiles for the next round. This is the first Azul game where different tiles have different values—the purple star is the most valuable of the six around the outside, and the red the least. (The red, purple, and yellow tiles have no designs on them, so they may present accessibility issues for people with color blindness.) It feels to me like the easiest to explain to a new player of all three Azul games, even though they all have some quirky rules that would probably be confusing to a non-gamer, at least at first, although on the whole none of these games is all that complex. If you like either of the first two Azul games, as I do, you’ll enjoy Azul: Summer Pavilion for the twist it provides on a familiar concept. If you’ve never played any of the Azul titles, however, I’d still steer you to the original, which is one of my all-time favorite games and is the most elegant of the three for its shorter rule set and simpler scoring.

Keith Law is the author of Smart Baseball and a senior baseball writer for The Athletic. His latest book, The Inside Game, is due out in April 2020. You can find his personal blog the dish, covering games, literature, and more, at meadowparty.com/blog.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.