Welcome to Crosstalk, wherein A.V. Club writers discuss their varied (or unvaried, as the case may be) perspectives on a pop-culture topic. This time, William Hughes and Jacob Oller try to square their disparate reactions to the house-building puzzle game Blue Prince. Warning: Spoilers await.

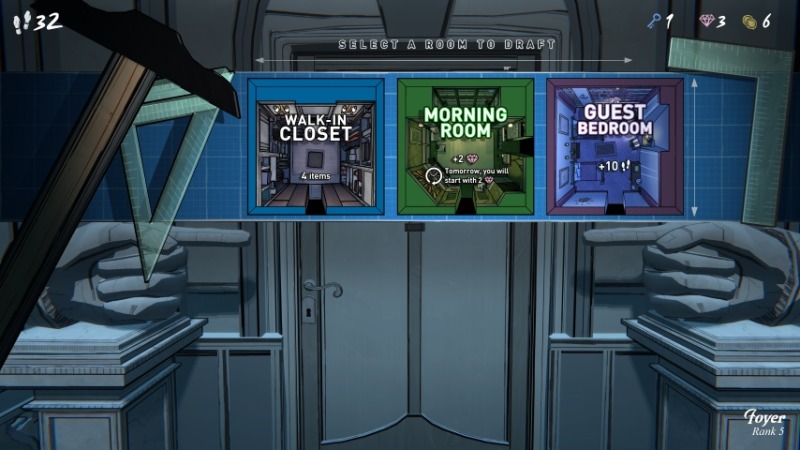

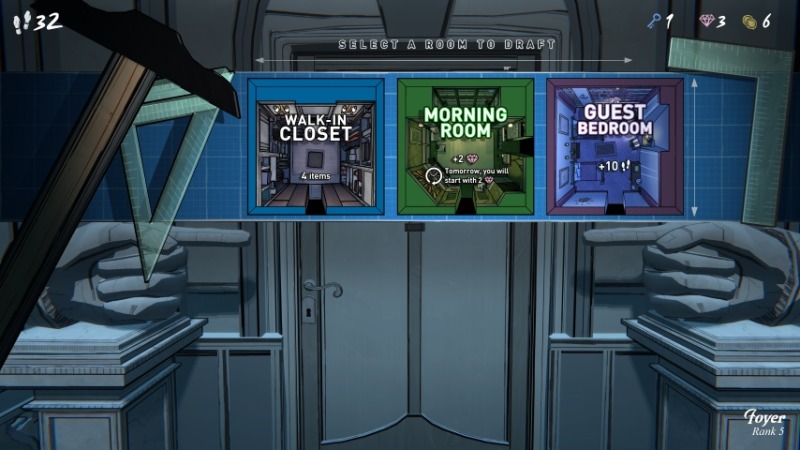

Jacob Oller: At the time of writing, I’ve put in almost exactly 80 hours into Blue Prince, the year’s indie gaming sensation that was made for me in a laboratory. I listed the roguelite puzzle game as one of 2025’s best because it turned me into a conspiracy-brained maniac who not only wanted to get better at figuring out the mysteries of my late grandfather’s mansion, but also get better at the house-building gameplay that would let me delve deeper into the mansion itself. And yet, William, I know the latter point is a place where we diverge on this game. You wrote a whole piece about your frustrations around the gameplay loop, the random bits of chance that determine if you’ll be able to draft the perfect room to get you further into the home, or get stuck at a dead end that’ll have you resetting your whole day. I know why I liked the combination of luck, skill, and progressive problem-solving (I’m an easily addicted sucker), but I’m curious if you have a theory as to why this particular game caught on with such a seemingly wide audience despite its genre niche, built-in frustrations, and complex lore.

William Hughes: Just to get my bona fides down on paper, Jacob, I’ll note that while my own Blue Prince playclock weighs in at a measly 28 hours, I did take a second run at the game a few months after my initial bounce off of it, and finally made my way to Mt. Holly’s fabled Room 46. (But no further: We can talk about the game’s elaborate—which is to say demanding—”post-game” in a minute.) And those factors that pulled me back to it, and sent me filling page after page in my Moleskine with notes about its various convoluted little puzzles, are those things about it which are undeniably both good and fascinating. Tied to a basic mechanical hook (draw tiles, place tiles, build house) that’s easy to grasp, Blue Prince is also one of the best pure mysteries that gamers have been presented with in some time, starting from a simple premise that unfolds, one “Hey, why is that like that oh shiiiiiiiii-” after another, into an incredibly complex, frequently satisfying puzzle box. And all of it arrives with a confidence that feels more and more like the hallmark of the small-teams approach to gaming that’s dominated the critical side of the hobby in 2025. There are dozens of little friction points in Blue Prince‘s design that gaming-by-committee would have summarily shorn off. (And a few that just gaming-by-William would have desperately liked to see trimmed, more on which in a second.) But the absolute confidence with which Dogubomb presented this beautiful puzzle box, seemingly out of the, ahem, blue, was genuinely staggering. It feels like the game they wanted to make, without compromise, and there’s something beautiful about that.

That being said, let’s get into my main sticking point: The random factor, which can cause a promising run to stutter to a stop because you pulled the wrong set of tiles when drafting a trickily placed room, or burnt too much stamina walking back to check a piece of information, or came up one key short to get a critical door open, or any of several other run-ending factors. Sell me, here, Jacob, because I had few feelings in gaming more intensely dispiriting in 2025 than slamming into one of these unpredictable walls while I was hot on the trail of an epiphany. What does the game’s random element add to its design?

Jacob Oller: So, my argument for the randomness builds off of the thing you highlight about the game: It’s a great mystery. And, for me, key parts of a great mystery game—just like great mystery TV shows or movies—is structure and pacing that trusts me to be smart enough to figure things out while giving me enough time to build up anticipation. I’m not so much advocating for getting to one of the final ranks and drawing three terrible red rooms, but for those unpredictable (but not entirely uncontrollable) roadblocks serving a greater purpose in the push-pull relationship the player has with the world and its clues. I might think I’ve had a breakthrough, piecing a series of numbers together in my own messy notebook, but my yearning excitement around testing a new theory, overcoming one kind of problem-solving obstacle, first needed to overcome another kind of obstacle. There are built-in cliffhangers, unscripted and generated organically. That delayed gratification kept me tantalized and encouraged me to think more tactically about the game. Seeing folks speedrun it really drilled that approach into my head, giving as much thought to how I moved through the house as I had to all the nuanced little pieces of lore within it. Plus, knowing that I couldn’t immediately rush to a specific room discouraged me from being too single-minded, which helped me gather a broad swath of clues. I might not be able to guarantee drawing the Shrine every day to work out a particular hypothesis, so there was always a need to have a back-up plan—some secondary motive to exploring. And, finally, I guess I’m also much more inclined to blame myself for screw-ups than to blame game design!

But, William, despite your frustrations with this element, you did make it to Room 46. You claimed your inheritance! What made you stop there?

William Hughes: This’ll be a mild spoiler, Jacob, but it speaks to a perversity of spirit that I find baked into Blue Prince‘s late-game design DNA: Getting to Room 46—the triumphant “end goal” of the entire video game—doesn’t actually let you poke around in Room 46! Instead, it triggers a credits sequence, and starts you on a new day. Want to actually see what old Grand-Uncle Herbert built an entire mansion full of esoteric bullshit to hide? Better jump through a brand new randomly generated set of hoops to get to the back of the house and get the necessary doors open. Despite appreciating some of the cleverness that reveals itself after you “win”—and having developed tools to help me mitigate the worst of the randomness—it was simply a bridge too far. In my mind now, getting to Room 46 (again!) is the game testing you to see whether you have the basic temperament to keep striving deeper into its secrets, as it attempts to jam you up at every turn. I consider it a courtesy that it informed me, in no uncertain terms, that I was merely a tourist in Mt. Holly. It didn’t help that, having resolved myself to ending my time with the game, I then glanced at spoilers for its later puzzles and saw how enigmatic, ambiguous, and complicated many of its terminal solutions could get; having weeded out the dilettantes, the game is clearly ready to get well and truly punishing.

How has that “post-game” Blue Prince content landed for you, Jacob? How deep down the rabbit hole have you gone, and has it gotten more or less fun as the complexity has continued to build?

Jacob Oller: Oh, it’s definitely trying to weed out everyone but the true puzzle perverts, and even I had my limits. (After looking up some of the extreme end-game material, it seemed more like a group project than a solo exercise.) But what helped was never establishing a connection in my mind between reaching Room 46 and being done with the game. It was clear as I filled page after page with charts, translations, codes, dates, and timelines that I’d only really call it quits when my curiosity was satisfied. So, reaching Room 46 was simply another milestone that got me closer to certain answers. Afterward, I felt conditioned to tackle much of the deep-lore complexity and, newly freed from that main goal, excited to tug on little threads I hadn’t yanked in a while. I only cut myself off when I ran out of ideas—when I hung it up, it was the first time I felt like frustrated old Jon Voight in National Treasure (“And that will lead to another clue, and that will lead to another clue! There is no treasure.”). And making that choice was liberating! I’ve been getting better at pulling away from games when they’re no longer serving me rather than beating my head against them until I’ve reached 100% completion. There’s a component of that to enjoying the more obscure passages of Blue Prince‘s labyrinth, allowing your own curiosity to both guide and limit you. I can understand why that seemingly bottomless well could be frustrating, but for me, it was a bit like the logic-puzzle version of those endless dungeon-crawlers, where there’s always another level, always better equipment and harder monsters. I found satisfaction in the process.

William Hughes: The funny thing, Jacob, is that I did, too. I want to close out our conversation by emphasizing that this isn’t a conversation between a person who hated Blue Prince and one who loved it. This is a talk between someone who vibed precisely with what the game was putting down, and someone who desperately wanted to. There are moments of Blue Prince that I’m going to treasure for years, puzzle solutions that filled my brain with the sublime joy of Working It All Out. (Hell, I put it on my end-of-year Best Of ballot, after all.) In my more cantankerous moments, I’ve asked aloud whether it wouldn’t be a better puzzle game if you stripped out the randomness, the house-building, everything in it that creates friction. And it might be! But it would be a less interesting game: Less textured, less weird, and, yet, less frustrating. Losing those elements might have made me happier, but they wouldn’t have made Blue Prince a better game.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.