Eno matches its subject's inventiveness with a dazzling, generative mosaic

With an ambitious formal gambit (no two screenings are alike), Gary Hustwit’s generative doc pays a fitting tribute to Brian Eno.

Brian Eno, the once would-be glam rock star turned record producer and ambient music composer, doesn’t think like most of us. Or, as Gary Hustwit’s dazzling new documentary Eno makes clear, the world-renowned musician works hard on any given day to wrestle himself out of well-worn ways of thinking, being, and, above all, creating. It’s fitting then that, not merely content with offering a portrait of Eno’s life and career, Hustwit has produced a film that borrows the artist’s ethos: Eno is a generative documentary. No two screenings are alike. Parameters have been set, but whatever version of it you will see won’t be the same as the one I caught on July 26th at the Roxie Theater in San Francisco.

It’s an ambitious gamble, one that risks feeling like a gimmick had Eno not spent much of his career striving to perfect such an approach to his own artistic creation. As he puts it in the doc—which shuttles between candid discussions with the artist, thrilling recording sessions with the likes of U2 and Talking Heads, and many an archival interview with Eno dating back to the ‘70s—to want music to be generative is a way to mimic and pay homage to the world around us. Eno has long been fascinated with the very systems nature builds, simple and intricate in equal measure, at times built from similar building blocks yet always entrancing for how different their assemblage appears.

What would it mean, he posits, if we created the way that nature creates? What if instead of laying out the piece of art as it is, we planted seeds and let them grow? These are questions that feel abstract, yet for Eno they’re remarkably simple and concrete. Having grown up alongside recording technology that allowed him to manipulate sounds and notes at whim, he has been able to constantly dabble with ways of making generative music. Music, that is, that grows out of parameters and recordings he creates (how often should notes be repeated, how calibrated should their cadence be, etc.) but that he doesn’t, in the end, wholly control. He just admires it.

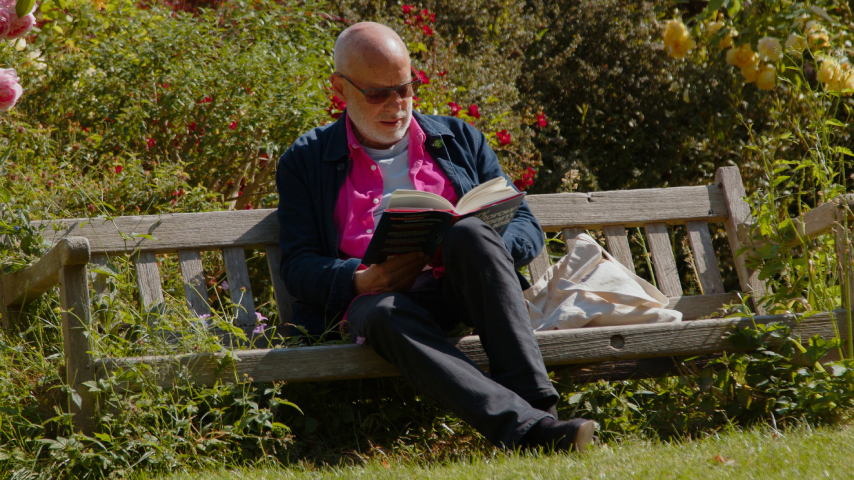

Such is the case in Hustwit’s documentary. Driven by Eno’s sensibility, the film is constantly scrambling itself, assembling and reassembling before your eyes: shots of Eno in a bright pink jacket and a white tee are refracted, creating a kaleidoscope image; sequences are clearly pulled out in arbitrary order, computer code and file names made visible in the bottom left hand corner letting us know how each is being retrieved at any given moment.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)