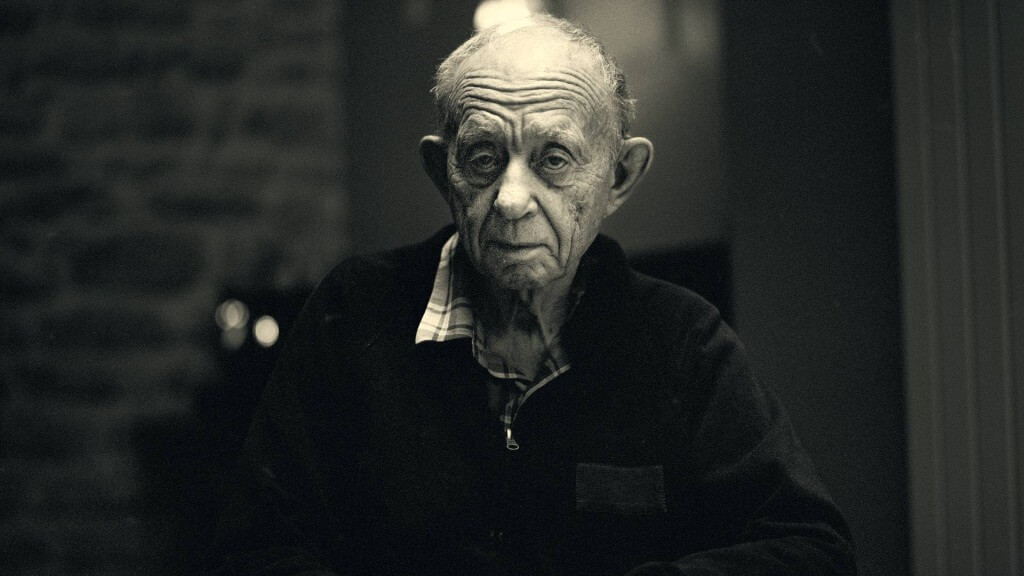

R.I.P. Frederick Wiseman, documentarian who observed human cost of institutional failure

The director of landmark documentaries free of narration and talking heads, including Titicut Follies and Welfare, Frederick Wiseman was 96.

Credit: Antoine Yar

Frederick Wiseman has died. The documentary filmmaker best known for capturing people trapped in the grinding gears of corrupt institutions for more than half a century passed peacefully, his family announced today. He was 96.

“For nearly six decades, Frederick Wiseman created an unparalleled body of work, a sweeping cinematic record of contemporary social institutions and ordinary human experience primarily in the United States and France,” Wiseman’s production company, Zipporah Films, announced in a statement. “His films—from Titicut Follies (1967) to his most recent work, Menus-Plaisirs – Les Troisgros (2023)—are celebrated for their complexity, narrative power, and humanist gaze. He produced and directed all of his 45 films under the banner of Zipporah Films, Inc.”

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, on New Year’s Day in 1930, Wiseman was the son of a lawyer, Jacob, who helped Jews escape from European nations engulfed by Nazism, and an aspiring actress named Gertude. Initially following in his father’s footsteps, Wiseman attended Williams College and Yale Law School, graduating in 1954 before being drafted into the army. Upon returning to the United States, he took a job teaching law at Boston University’s Institute of Law and Medicine. That’s when he began to show his mother’s influence as Wiseman made his first steps outside the court and classroom to produce Shirley Clarke’s The Cool World, a fictional narrative drama that cast real Harlem kids and gang members. He followed it with his first documentary, Titicut Follies, in 1967. Shot over 29 days in Massachusetts’s Bridgewater State Hospital for the Criminally Insane, Wiseman’s camera observed staff abusing and degrading patients forced into inhumane living conditions. The film shocked the Massachusetts government, which accused Wiseman of breaking an “oral contract” that gave the state final cut and violating the patients’ privacy and dignity. As a result, the film remained banned from public screenings until 1991.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.