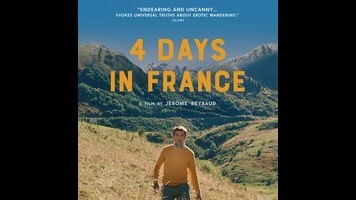

Grindr plays a starring role in the epic on-the-road romance of 4 Days In France

The queer French road movie 4 Days In France features three main characters. There’s Pierre (Pascal Cervo), a diminutive, soft-spoken guy in his 40s who’s apparently had enough, though it’s never made clear exactly why he gets into his white Alfa Romeo at the beginning of the film and just starts driving, with no destination in mind. There’s Paul (Arthur Igual), Pierre’s impressively mustachioed live-in boyfriend, who waits around in confusion for 24 hours before renting a cheap Volvo and setting out in pursuit. And then there’s Grindr, the gay networking app, which Pierre employs throughout the film as a means of finding strange men to screw and/or beds for the night, and which Paul uses to monitor Pierre’s ever-shifting location. Grindr’s distinctive notification alert becomes a running aural joke, and the turning point of Paul’s parallel storyline arrives when he recognizes Pierre’s penis among the dozens of dick pics he’s receiving.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.