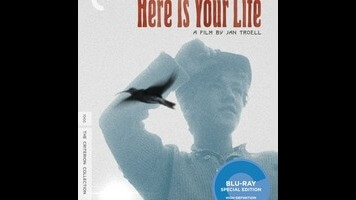

Judging from his films that have made it to the U.S.—there are quite a few that haven’t—Swedish director Jan Troell tends to favor sprawling, shapeless portraiture. Over the course of his five decades in the business (he’s now 83), Troell has made movies about Norwegian author Knut Hamsun (Hamsun); Swedish photographer Maria Larsson (Everlasting Moments); and, most recently, outspoken anti-Nazi newspaper editor Torgny Segerstedt (The Last Sentence). Criterion’s new edition of his 1966 debut, Here Is Your Life, suggests that his sensibility was fully formed right from the outset. Running just shy of three grueling hours, and adapted from the second in a series of four autobiographical novels by Eyvind Johnson, it’s a doggedly anecdotal narrative that barely even feints at any larger purpose, content simply to follow a teenage boy as he leaves home and proceeds to toil at a variety of low-paying jobs. The talent that went into the film’s construction is unmistakable; why Troell felt any pressing need to make it is a lot less clear.

Granted, it looks gorgeous. Much of the film, which is set during World War I, takes place outdoors, and Troell, who served as his own cinematographer, captures the stark northern Swedish landscape in striking black-and-white images that would make a superb collection of still photographs. Certainly, the rivers and forests are more captivating than is nominal protagonist Olof Persson (Eddie Axberg), who’s first seen returning to his childhood home after spending an unspecified amount of time living in foster care, due to his father’s terminal illness. Rather than stick around to watch Dad die, Olof decides, at age 14, to strike out on his own, getting hired at a sawmill and working his way up from log transporter to buzzsaw operator. (Those might not be the official job titles.) He’s not great at dealing with authority figures, however, and winds up quitting one position after another, though he seems happiest during a stint operating a new machine called a cinematograph. The “action,” such as it is, covers several years, with Olof’s employment history and romantic liaisons serving as the movie’s main focus.

In a novel, the protagonist’s interior monologue can be compelling even if they’re not necessarily doing anything overtly exciting. On-screen, in the absence of a voice-over (which is the case here), the only way to make this approach work is to a) ensure that each individual anecdote functions as a first-rate short film, and/or b) structure the narrative so that it gradually builds to an emotional catharsis, gathering steam along the way. Here Is Your Life does neither. There’s a numbing sameness to Olof’s so-called adventures, which take the dreaded form of “and then this happened and then that happened and then this happened and then…” Toward the end (which is to say, deep in the movie’s third hour), the kid does start to develop a nascent political consciousness, making Marxist speeches about workers’ rights, but it’s not at all a culmination—just another random direction for the story to take, quickly forgotten. Olof’s romance with “Queen Of The Carnival” Olivia (Ulla Sjöblom), an older woman who teaches him the sexual ropes, has only a bit more sticking power, while his other girlfriends are generic enough to be interchangeable.

Even Here Is Your Life’s most fervent fans (and its selection by Criterion indicates that they’re out there) must be exasperated by the film’s complete and utter non-ending, though it’s entirely in keeping with the waywardness that precedes it. Again, Troell adapted the second novel in a four-volume series, so the absence of a strong resolution is no big surprise. But it feels vaguely insulting when Olof just trudges off to whatever job awaits him next, as he’s been doing since we first met him, and the camera suddenly cranes way up into the sky to signify that we won’t be following him this time—the movie is now over. There’s no particular reason why it couldn’t have ended an hour earlier, at virtually any given point, nor why it couldn’t (perish the thought) continue for another three, or six, or nine hours in the same vein. It’s expertly made in every respect save for demonstrating a purpose, a reason for being, even a reason for stopping. Your life may, in fact, resemble this film, as the title implies, but that doesn’t mean you want to see such low-key formlessness reflected back at you.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.