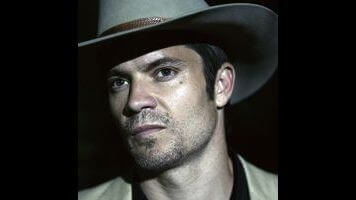

Justified: "Bulletville"

Well, you can’t say that episode didn’t live up to its title, can you?

After weeks of relative restraint, at least on Raylan’s part, “Bulletville” unleashed all the murderous tension that’s been building up between and among the Givens and Crowder clans, as well as the hostile visitors from Miami, who aren’t too keen on losing $2 million in ephedrine. (Immediate exchange-of-the-night candidate. Art: “Somebody is going into the meth business in a big way.” Raylan: “Or the folks in Harlan are really, really congested.”) For a show that’s dedicated in no small part to delivering the goods, the finale of Justified was a great piece of a meat-and-potatoes entertainment, paying off a season’s worth of slow-burning conflict with a violent, bloody Old West-style reckoning.

But “Bulletville” wasn’t devoid of character-based revelations, either. I’d been arguing for some time that Boyd’s prison conversion was merely a ploy to gather a new criminal “flock,” with Christianity replacing neo-Nazism as another belief system that his charisma can sell to persuadable thug. There’s been a wonderful ambiguity to his destruction of the local meth business: Does he really want that “poison” out of Harlan or does he want that territory for himself? Many of you smart folks on the comment boards correctly speculated that Boyd’s conversion was in fact real, and to you I tip my hat. In my defense, however, Johnny Crowder thought the same thing and he’s known Boyd a lot longer than any of us have.

Having Boyd on the same side as Raylan throws the season—and the series to come—into a very different light. For one, we can understand to an even greater extent why Raylan deliberately botched the killshot when he took down Boyd in Ava’s living room. The two have a history together in the mines, and a partnership in conditions that dangerous forges bonds deeper than an ordinary workplace, closer to sharing a foxhole than sharing a cubicle. But by sparing Boyd’s life in that situation, Raylan must have known there was something redeemable about him—or at least redeemable enough to move his gun a centimeter to the side. We know the Crowder family to be duplicitous and evil by and large, and goodness knows that’s reflected in Boyd’s genetic profile. Yet he’s a troubled soul, too, and a disappointment to his father, which could only be an argument in his favor.

Boyd’s conversion also complicates his relationship with Raylan all the more, presenting them now as two sides of the same coin. Boyd shares Raylan’s goal of expelling the meth “poison” from Harlan, and seeing them team up for the cabin shootout at the end of “Bulletville” was a season highlight, an ironic conclusion to their cat-and-mouse game. You could even say they share an old-fashioned, trigger-happy ethos when it comes to dispensing justice. But for all of Raylan’s creative interpretations of the law, he’s not a citizen operating on a freelance basis; though not shy about drawing his firearm, he’s also had to the walk the line in order to keep his job. Boyd proves a useful ally in the fight against the other Crowders and the Miami people, but his Batman routine will pit him against the authorities in future circumstances. So the alliance is only temporary.

The sincerity of Boyd’s mission gives “Bulletville” a surprising emotional resonance, too. His willingness to turn the other cheek when Bo comes a-callin’ is something else; there’s power and strength in his non-violent response to the beating Johnny puts on him, but even he’s stunned by his family’s relentless, remorseless pursuit of its own interests. Johnny just keeps slugging away cravenly as Boyd quietly absorbs every blow, and when Boyd finally runs for the hills, the Crowders decimate his congregation, leaving them dangling like gruesome ornaments. The former I’m sure he anticipated. Boyd couldn’t have expected his eradication of daddy’s business to come without consequences. (Another line-of-the-night candidate, from Bo: “Who am I kidding? I can’t hurt my own son. Johnny, hurt my son.”) The latter genuinely crushes him, and it’s an odd sensation to find yourself feeling for a man who had once led a band of neo-Nazis and had seemed diabolical even when he “converted.” I suspect this event might be an awakening of another sort of Boyd when we get to Season Two.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.