Long before Spider-Man, Sam Raimi cast Liam Neeson as a wilder, grosser superhero

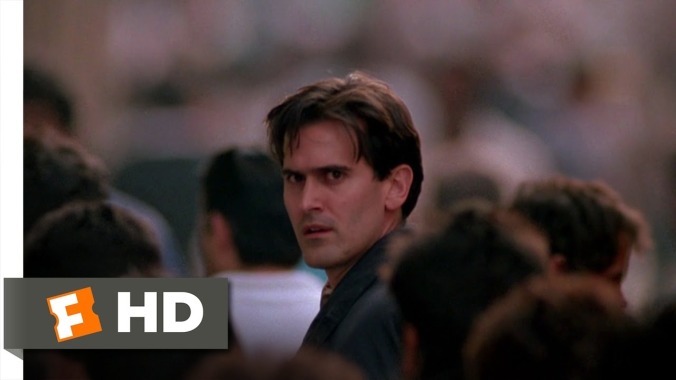

Darkman (1990)

Sam Raimi wanted to make a superhero movie. After gifting the world with his absurdist 1987 horror-comedy masterpiece Evil Dead II, Raimi chased the rights to make movies out of both Batman and The Shadow. Both times, he failed. So he invented his own superhero—one who was really more of a deranged and revenge-crazed mad-scientist type. Raimi’s Darkman isn’t a product of some intellectual-property agreement. It comes straight from his own fevered brain (and from the crew of screenwriters who helped him turn that idea into a script). Years later, of course, Raimi would finally get a crack at making big-budget superhero blockbusters; without his Spider-Man movies, it’s entirely possible that we wouldn’t be living through today’s superhero movie boom. But as great as those Spider-Man movies could be, they never showed the same dank, freaky, euphoric spark that Raimi had when he made Darkman.

Raimi liked the idea of a hero who could change his own appearance, and he was also into the old Universal Studios monsters, the misunderstood freaks who lashed out at the society that rejected them. And so he turned Darkman into a brilliant scientist who’d been horribly scarred, his face more or less removed after gangsters burst into his lab and blew it up. Darkman, then, was a character driven insane, one who couldn’t be out in the light for more than 99 minutes before the skin literally melted off his body. For a director like Raimi, drawn to both dreamlike, hyperreal gore effects and drunkenly ecstatic camera pyrotechnics, Darkman was a near-perfect vehicle for ideas and for aesthetic.

Darkman isn’t a superhero, exactly—at least not in the way that we tend to understand the term. Only the Danny Elfman music suggests that we’re watching a post-Batman superhero movie. The rest of the time, Darkman is a deeply bugged-out early-’90s hard-R action movie. The Darkman character is never really driven by a need to protect the innocent at large or to serve the cause of justice. Instead, he’s crazy for vengeance, and the only person he cares about protecting is his girlfriend. Darkman’s costume is just a black hat and a ratty, billowing trench coat that he dug out of a dumpster. Nobody ever calls him Darkman, and he only uses that name once, in the end-of-movie narration—when Bruce Campbell, Raimi’s Evil Dead star and his original choice to play Darkman, shows up for a quick cameo.

Instead of Campbell, Raimi ended up with a hulking Irishman whose previous role was as Patrick Swayze’s vengeful brother in the 1989 crime movie Next Of Kin. (Liam Neeson has apparently been seeking vengeance in movies for longer than most of us realized.) A year before that, Neeson had played the music-video director who oversaw Jim Carrey’s Axl Rose impression in the Dirty Harry movie The Dead Pool. (This scene remains one of the greatest weird historical footnotes in film history.) Neeson had plenty of experience as a stage actor, but he’d broken into film in B-movies like Excalibur and Krull. He wasn’t a respected screen actor or a movie star yet; both of those would come later. As his co-lead and love interest, Raimi cast Frances McDormand, who’d mostly just done early Coen brothers movies at that point. (When he made Darkman, Raimi was sharing a house with McDormand and with the Coen brothers, which probably put her front and center for the role.) In retrospect, it’s possible that we’ve never had a superhero movie with two more overqualified leads.

Both Neeson and McDormand brought a gravitas that seems almost out of place in Darkman. Early on in the movie, before his transformation, Neeson brings a serious sympathetic soulfulness to a barely written role. But when he turns into Darkman, and when he’s acting under a ton of latex makeup, Neeson only has to give off frantically cartoonish intensity. McDormand, meanwhile, apparently clashed with Raimi over his desire to turn her into a damsel in distress. Her steely, three-dimensional toughness—again, in a role that’s not especially complicated—adds dimensions to a character who didn’t necessarily need them.

But Darkman is not an actors’ showcase. It’s Raimi’s chance to show off, his first time getting any sort of budget for his insanity. The movie opens with a batshit warehouse shoot-out, a riot of car-flips and explosions. That scene looks something like an homage to John Woo’s Hard Boiled, except that Darkman came out two years before Hard Boiled. (It’s entirely possible, now that I think about it, that Darkman influenced the Hard Boiled warehouse shootout.) After the shootout ends, we see Larry Drake’s crime boss Robert Durant, one of the movie’s villains, methodically chopping off the fingers of a guy we’d previously seen filing his nails. It’s nasty.

That nastiness returns in the movie’s best scene. Temporarily reconstructing his old face and hiding his scars from his girlfriend, Darkman tries to pretend that he’s back, that everything’s fine. He takes her to an amusement park, where he tries to win her a giant stuffed elephant at a midway game. But he’s got to get back to his lab before his face melts, and the nearby carnival freak has Darkman thinking about how nobody would ever love him if they saw how he really looks. The carny running the game tries to cheat Darkman out of the prize, so he freaks the fuck out, twisting the guy’s finger back and throwing him through a wall, his eyes bugging out of his head. It’s Raimi returning to the pitched-up, near-slapstick filmmaking that made Evil Dead II such a perfect movie. No other filmmaker could’ve done it. No other filmmaker would’ve even tried.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)