The main plot line of R100 concerns Takafumi Katayama (Nao Ômori, Ichi The Killer), a mild-mannered businessman who gets his jollies by signing up for an unconventional pro-domme service where he is randomly attacked by leather-clad women in public. Contracts cannot be canceled halfway through, the owner of Bondage Gentlemen’s Club warns him as they circle the club on an old-fashioned carousel. (This club has no whips, chains, or other typical BDSM trappings, but it does have an indoor pool.) Blinded by lust, Katayama agrees. But when his arrangement with the “Queens” begins to encroach on his work and family lives, Katayama tries to get out anyway. Then a surprise late-night visit leads to a freak accident, necessitating a visit from the club’s intimidating female CEO (6’9” former pro-wrestler Lindsay Hayward).

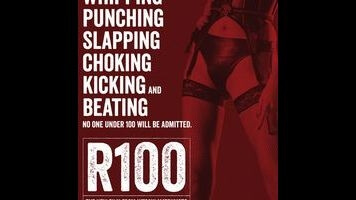

Layered on top of this is a meta B-story in which an appalled ratings board is attempting to figure out what rating to give the movie. The ancient “director” has insisted that this is the film he needs to make, and only centenarians will understand it, a timid assistant tells the incredulous suits. Thus, they decide to rate it R100—no one under the age of 100 admitted. (A R18 is the Japanese equivalent of an NC-17.)

Aside from a cheeky running gag about earthquakes, Matsumoto says that he isn’t trying to make a larger social point here. But he does approach the subject of masochism from an interesting viewpoint. Not only does R100 refrain from lampooning Katayama’s desire to get the crap beat out of him, it’s sympathetic to it. Take the scene where we see the character leaving the hospital where his wife is lying in a coma. The sky is gray, the music is melancholy, and it’s all very sad. Katayama walks with his shoulders slumped and his head down. Then, out of nowhere, a woman clad in leather and high heels comes running towards him, knocks him to the ground, and starts kicking him violently. His face begins to contort in blissful ripples—an effect rather like the lusty nosebleeds common in anime—and one can feel Katayama’s release, the relief of feeling any sensation, even a painful one, after the numbness of grief.

Transgressive, unclassifiable, ridiculous—all these words apply to R100. But upon reflection, it becomes clear that Matsumoto has achieved something remarkable here: He’s made a film at once boundary-defying and really fun to watch. It’s not for everyone, and best appreciated by those who already have a taste for such things (kind of like BDSM, actually), but the 100-minute running time flies by, and the film remains entertaining even when it begins to spiral out of control. To aficionados of the bizarre, R100 will be a rare pleasure indeed.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)