Benatar was actually uncomfortable with marketing herself visually in the video—a sentiment shared by many artists in the pre-music video era. Obviously, MTV became a massive success (for a time), and performers eventually cottoned on to the power of the image to enhance their music.

“Girls Just Want to Have Fun” by Cyndi Lauper, 1983

When you think of appointment music video viewing, Cyndi Lauper’s “Girls Just Want to Have Fun” is likely one of the first. It indelibly captures the frivolity of the accompanying song, which signalled the dawn of a new breed of empowered female pop stars who called the shots. (Madonna’s early visage is a clear homage to Lauper.)

“We needed videos that represented women better,” Lauper has said. “I had women of every race in my videos, especially ‘Girls Just Want to Have Fun,’ so that every girl who saw the video would see herself represented and empowered, whether she was thin or heavy, glamorous or not.”

Lauper’s own mother played her mom in the video, while the wrestler Captain Lou Albano was cast as her dad, ushering in the “Rock ’N’ Wrestling Connection,” a partnership between music stars and wrestlers like Albano, Rowdy Roddy Piper, and Hulk Hogan (who appropriated the idea with his Hulk Hogan’s Rock ’N’ Wrestling cartoon, as the controversial wrestling star who died in 2025 was wont to do) that is largely credited with the mainstream acceptance of wrestling in pop culture.

“Slave to the Rhythm” by Grace Jones, 1985

If only all artists could combine clips from their previous videos into one uber-video, as Grace Jones did for “Slave to the Rhythm,” incorporating clips from “My Jamaican Guy” and “Living My Life,” both of which riff on minstrelsy and blackface. Directed by Jean-Paul Goude—who was in a relationship with Jones at the time—the video features the artist’s infamous eponymous photo of Carolina Beaumont, also known as “The Champagne Incident,” which later inspired Goude’s 2014 Paper magazine “Break the Internet” photoshoot of Kim Kardashian. Ahh, the appropriation critiques of “Slave to the Rhythm” still remain relevant 40 years later…

“Justify My Love” by Madonna, 1990

One is spoilt for choice when it comes to Madonna: whether it’s the notorious video for “Like a Prayer” (1989) which angered the Catholic Church and was banned on most other music video channels; the similarly-banned “What It Feels Like For a Girl” (2000); or the culturally appropriative “Vogue” (1990), Madonna created the concept of a pop star having “eras” long before Taylor Swift made billions doing it.

With each era, Madonna courted controversy, perhaps none more so than her early 1990s exploration of sex in her 1992 album Erotica and her accompanying coffee table book Sex—both of which pushed the boundaries of what a pop star could say and do, especially in the wake of the HIV/AIDS crisis, which Madonna was a vocal advocate for.

But “Justify My Love,” off her 1990 greatest hits album The Immaculate Collection, prefaced this era, exploring sex work, BDSM, voyeurism, and queerness in a black and white clip that was banned by MTV, setting a precedent for Madge. Erotica would also be subsequently banned by the station.

“Nothing Compares 2 U” by Sinead O’Connor, 1990

Compared to the maximalist videos thus far, Sinead O’Connor’s “Nothing Compares 2 U” pioneered the power of an unadulterated banger that needs nothing more than a striking bald woman belting to elicit a response.

“It was a time when you hadn’t really come across angry women,” O’Connor said of the video. “I wasn’t standing there with blond hair, saying, ‘Oh baby, do me.’”

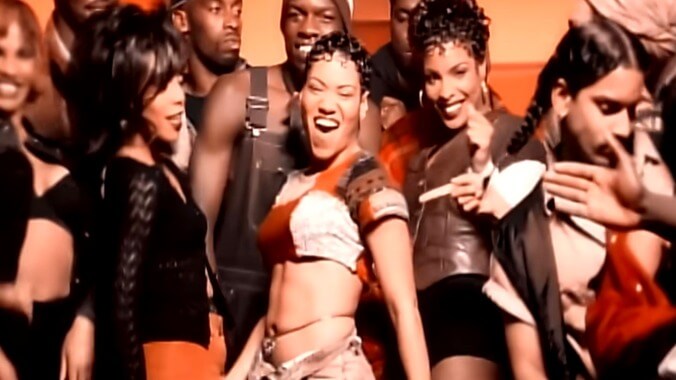

“Whatta Man” by Salt-N-Pepa & En Vogue, 1993

Like Madonna, there’s a strong case for including nearly all of Salt-N-Pepa’s music videos on this list. The rap trio, which consists of Cheryl James, Sandra Denton, and Deidra Roper, flipped the script on the misogynoirist conventions of male-dominated rap and hip hop. Their lyrics and videos consistently turned the male gaze into something more egalitarian, ultimately paving the way for artists like Missy Elliot, Cardi B, and Megan Thee Stallion.

“Whatta Man” topples a lot of these tropes, placing the women of both groups as the drivers of their own desires. During the group dance scenes, the women are dressed casually in denim shorts and flannel shirts—this was the early ’90s when grunge reigned supreme, after all—having fun, taking up space, and calling the shots.

“Window Seat” by Erykah Badu, 2010

While the video for “Window Seat” was filmed in Dealy Plaza, where John F. Kennedy was killed in 1963, and meant to evoke his assassination, the parallels to Trayvon Martin, the black teenager who was shot dead by neighborhood watchman George Zimmerman just two years after the video was filmed, are clear.

Badu begins the video wearing a hoodie—the garment Martin was also wearing when he was murdered, which became a symbol of the Black Lives Matter movement—and gradually peels off each layer of clothing in a guerrilla-style one-shot. She is eventually nude, but pixellated, at which point she is shot by an off-screen gunman, an act of violence that is pointedly not censored. “They are quick to assassinate what they do not understand,” Badu says in the voiceover. “This is what we have become. Afraid to respect the individual. A single person within a circumstance can move one to change. To love herself. To evolve.”

As the camera pans away from her dead body, she is reincarnated as a nude woman with braids, a reference to “the character assassination one would go through after showing his or her self completely.”

“***Flawless” by Beyoncé, 2013

Being a Black woman in the music industry who had previously decried feminism, Beyoncé long drew the ire of feminists, including bell hooks, who once called her a “terrorist” for her perceived capitulation to capitalism and white beauty standards. But we all learn, grow, and change our politics—and if there was ever any doubt about whether the trailblazing Queen Bey supported gender equality, “***Flawless” put that to bed.

There’s nothing especially remarkable about the black-and-white video for the 11th track on her fifth studio album, especially compared with the stripped-down “Rocket,” the disco vibes of “Blow,” or the sexual fantasy of “Partition.” But it’s the inclusion of a portion of the Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s TEDx Talk defining a feminist as “the person who believes in the social, political, and economic equality of the sexes,” that gives “***Flawless” a spot on this list.

Prior to “***Flawless,” celebrities—and, by extension, the general public—were confused about what it meant to be a feminist, and would often obfuscate the question. But after the video and Bey’s performance of “***Flawless” as part of a self-titled medley while accepting the Video Vanguard award at the 2014 MTV Video Music Awards, during which she stood in front of a lit-up sign emblazoned with the word “feminist” (my Halloween costume that year), it was suddenly cool to be a feminist. Other celebrities, like Taylor Swift and Kim Kardashian, soon waded into the discourse, ushering in a full-blown new wave of feminist discussion: from “choice” feminism to “marketplace” feminism coined by Bitch magazine founder Andi Zeisler to the scourge of the girlboss. Were we ever so young?

“Pynk” by Janelle Monáe, 2018

In between the commodification of feminism signified by “***Flawless” and the next entry came the #MeToo movement in late 2017—presaged by the first election of President Donald Trump and the Women’s March. I attended the latter, as did the ArchAndroid Janelle Monáe, which no doubt inspired the nonbinary singer-actor’s subsequent album, Dirty Computer, and its lead single, “Pynk.”

The video, a celebration of the Black woman’s body, features women wearing underwear emblazoned with the phrase “I grab back,” a reference to Trump’s infamous “grab ’em by the pussy” line from the leaked Access Hollywood tape shortly before the 2016 election.

Vagina iconography appears elsewhere in the video as well, most iconically in the pink ruffled pants worn by Monáe and their dancers, from which Tessa Thompson—long rumored to be in a relationship with Monáe—cheekily (or is that flappily?) peeks out from between.

“Woman’s World” by Katy Perry, 2025

If “***Flawless” signalled the popularization of feminism, Katy Perry’s “Woman’s World” was arguably its death knell.

Perry has had a hard slog of it lately, with her breakup from long-time beau Orlando Bloom, her ill-received trip to space, and the endless pans of her most recent album, 143, and its associated Lifetimes tour (because The Eras Tour was already taken). Sparking (or foreshadowing) this long list of bad luck and/or decisions was 143‘s lead single, “Woman’s World,” which, honestly, wasn’t panned enough.

Aside from being a bad song filled with empty platitudes reminiscent of the pop empowerment she once found success with in 2013’s “Roar,” “Woman’s World” was produced by Dr. Luke, the producer Kesha was embroiled in a years-long legal battle with over allegations that he sexually assaulted Kesha and kept her in a predatory recording deal. The two finally settled their suit in 2023 as Kesha embarked on a new phase of her career with the support of her fellow pop stars Lady Gaga, Ariana Grande, and Swift, who donated $250,000 to Kesha’s legal fund. Perry was notably absent from that cohort and continued to work with Luke.

I’m not saying the AI-looking ass “Woman’s World” video, which co-opted Rosie the Riveter iconography (Perry later said it was satirical, which, if you have to explain i,t it didn’t land), contributed to MTV’s closure and the death of the music video as an art form, but I’m not not saying that…

What are your favorite feminist music videos? Which ones did we miss? Sound off in the comments.

Scarlett Harris is a culture critic and author of A Diva Was a Female Version of a Wrestler: An Abbreviated Herstory of World Wrestling Entertainment.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.