Survivor (Classic): “The Marooning”

When Survivor premièred in the summer of 2000, the reality television genre was still new enough that there wasn’t consensus on what to call it. Writing in The New York Times, Bill Carter referred to Survivor and Big Brother as “televoyeur shows; in a Time cover story, James Poniewozik coined the term “VTV,” or “voyeur television.” Both descriptions are fundamentally more accurate than the now-standard term, “reality television,” a name that has a permanent set of air quotes around it.

By the year 2000, The Real World had already been around for eight years, and its spin-off Road Rules for nearly as long, but the two shows weren’t enough to constitute an entire genre. But at the turn of the millennium, the networks started to catch on to a trend that, by then, had taken Europe by storm. In the summer of 1999, Who Wants To Be A Millionaire?, an adaptation of a hugely popular British series, became an unexpected smash on ABC. It was a sexed-up game show and not a reality series, but its success sent a clear message to television executives: Americans will watch unscripted shows in primetime. In February of 2000, Fox aired Who Wants To Marry A Multi-Millionaire?, a two-hour special which culminated in the televised marriage of Rick Rockwell and Darva Conger—a union that was annulled two months later amid revelations about Rockwell’s history of domestic abuse.

Then, on May 31, 2000—just in time for summer—came Survivor, a show that simultaneously played upon two of our most primal impulses: voyeurism and Darwinist competition. As one enthusiastic viewer described it to The New York Times, “'It's like Real World meets Lord Of The Flies.” While Survivor wasn’t the first show in the “second wave” of reality television, it was undoubtedly the tipping point. It premièred with a bang and steadily attracted more viewers throughout the summer; in a rarity for CBS (some things never change) it was especially popular among the coveted 18-34 demographic. The Survivor finale was watched by more then 50 million American viewers, making it the second-most watched television episode of the ’00s, second only to the finale of Friends. It was, in short, a sensation. Television executives, never ones to worry about originality, quickly followed suit: In the next two years, a spate of reality (and reality-ish) shows would flood the airwaves, including The Mole, American Idol, The Weakest Link, Joe Millionaire, and (my personal favorite) Temptation Island.

An adaptation of a relatively obscure Swedish series called Expedition Robinson, Survivor was an overnight sensation 13 years in the making. A trio of British producers which included the youngest member of the House of Lords and Bob Geldof (yes, that Bob Geldof; I had no idea either) had been developing the idea for over a decade, to no avail. Eventually, they partnered with former British paratrooper Mark Burnett and sold the idea to Swedish television. Expedition Robinson was a hit, but its success was clouded by the fact that the first contestant eliminated from the show also committed suicide. Controversy notwithstanding, Burnett and company sold the idea to CBS for a bargain price of an estimated $700,000 an episode. Survivor-mania took everyone by surprise. As producer Michael Davies told The New York Times, “A year ago, if I had said the two biggest things in television are going to be a young-skewing show on CBS that’s a reality concept based on a British-created Swedish television program produced by a former British paratrooper and part owned by a member of Parliament, and a prime-time quiz show hosted by Regis Philbin, that would have been an inconceivable notion.” (If you want to know more about the show’s bizarre origins, I highly recommend reading the entire Times piece.)

There are many reasons for the rise of reality television: the winnowing of the network television audience and the subsequent need for more cheaply produced entertainment; a cultural epidemic of narcissism and an increased obsession with fame and celebrity; the pressure for network television to produce original content year round in order to reduce viewer migration to cable. But revisiting Survivor, and especially looking back at the near-hysterical reaction to it (one critic called it “Jerry Springer with sand, skin rashes and bad food”), I’m struck by how intimately the rise of reality TV is tied to that of the Internet, to millennial fears about surveillance, privacy, and technology. A few weeks after the premiere of Survivor, CBS unveiled Big Brother, a show whose name explicitly played on these fears—even for Americans who’d never read a word of Orwell, the message was hard to miss: you are being watched.

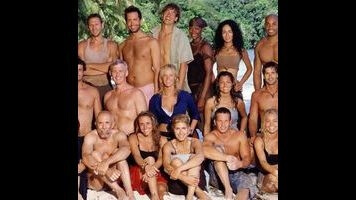

My opinion lines up more closely with Nancy Franklin, who wrote an enthusiastic if qualified review in The New Yorker. “It’s hardly a sign of anything sinister or civilization destroying that Survivor has been a success. It’s ripping drama, plain and simple,” she said. But despite her uncomplicated enjoyment of the show, Franklin also called it a “one-shot deal in my house.” And truthfully, that’s more or less the way I feel—and have felt—about most reality shows: I’ll get into it for a while, usually two or three seasons, then move on. Project Runway, America’s Next Top Model, The Real Housewives, The Hills: I’ve been obsessed, and subsequently bored, by all of them. I’d stop short of saying that I’m an advocate of reality television, but I’ve been an occasionally enthusiastic fan. When Survivor-mania swept the country in the summer of 2000, I was a little late to the game. I was in college, waiting tables over the summer, and my roommate was hooked. I didn’t start watching until the last few episodes, but I was instantly drawn to the characters: Rudy, the cantankerous but lovable old guy; Susan, the redneck with the grating accent; Richard, the manipulative, arrogant creep with the incongruous baby face.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.