The Elizas is a belly flop of a thriller from the author of Pretty Little Liars

The publication of Gone Girl sparked something of an arms race within literary thrillers, a long-dominant genre that nevertheless received a renewed burst of attention and popularity with Gillian Flynn’s massive bestseller. Authors took her ball and ran with it, each trying to outdo their peers by having the twistiest of narratives and the least-reliable of narrators.

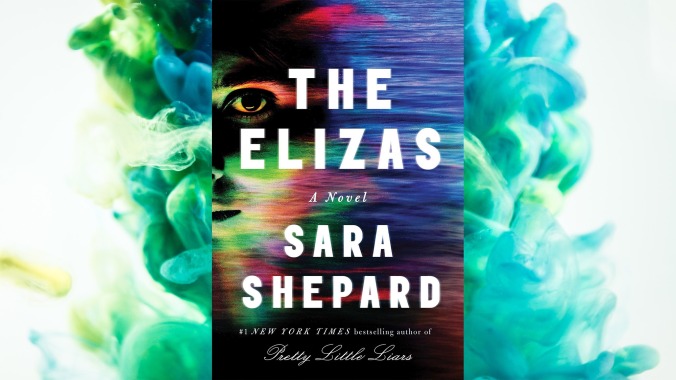

The problem with this is that thrillers, like bombs, are built out of volatile ingredients, and an unsteady hand means they blows up in the face of the maker. The best thriller plots drive inward, effective for what they reveal about the characters, as opposed to outward and the writer’s willingness to unveil a triple-cross betrayal or whatever is intended to shock. Turns out there’s a whisper-thin line between topping another author and just plain toppling over, and Sara Shepard’s The Elizas stumbles so dramatically that from page two on it’s closer to gut busting than hair raising. In the event it follows The Girl On The Train or Big Little Lies to Hollywood, the David to give it the treatment it deserves isn’t Gone Girl’s Fincher but Airplane!’s Zucker.

This one’s unstable narrator is Eliza Fontaine, introduced raiding a hotel minibar, blacking out, and then waking up in a hospital, having nearly drowned in a swimming pool. Was she suicidal? Drunk and clumsy? Pushed in? Pushed in with intent to kill? She thinks she remembers someone fleeing the scene, but no one believes her. She’s a doubly unreliable narrator, see: not just an alcoholic, but also amnesiac from a recent brain operation. (A psychiatrist gets a timeless bit of dialogue: “That must have been tough to have a train tumor last year, huh?”)

The question of what happened that night and what led up to it is the driving question behind The Elizas, with Fontaine attempting to rebuild her fractured memory and determine whether she was, or remains, in danger, or even whether she herself did something criminal she can’t recall. In order to accommodate Shepard’s big narrative hooks—the brain-tumor subplot especially seems destined for bad-book cult immortality—the story is forced to go ludicrous, with outlandish coincidences, characters being told obvious lies that they believe just ’cause, and other narrative pieces that have to be pounded together, like Homer Simpson doing a jigsaw puzzle, in order for things to progress. The plotting is the literary equivalent of a comb-over for plot holes: just as thin, and just as effective as hiding what it’s supposed to cover.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)