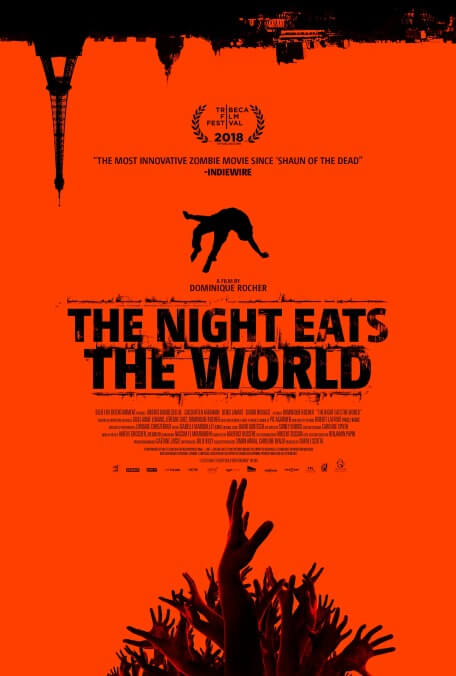

If the zombie apocalypse actually happened, what would you do? Presumably, your first priority would be to get somewhere where you’re not in immediate danger of being eaten. And most zombie stories revolve around just that: a survivor’s (or survivors’) quest to find safety. But Dominique Rocher’s feature debut The Night Eats The World, based on Pit Agarmen’s novel of the same name, asks a follow-up question: Then what?

Oslo, August 31 star Anders Danielsen Lie stars as Sam, a frankly pretty nondescript musician who, as the film opens, arrives at his ex-girlfriend’s apartment to collect some stuff he left behind. Annoyed to discover that she and her new boyfriend are having a raucous party at the same time as his awkward errand, Sam retreats to a back bedroom. He then proceeds to pass out in an armchair as the party rages just outside the bedroom door. Then a plague of zombies descends on his fellow partygoers, ripping them to shreds and leaving the apartment a blood-spattered mess. Sam, somehow, sleeps through the whole thing. When he wakes up the next morning, he slowly realizes that he’s the only living human left in the building, and perhaps even the whole world.

The majority of the film follows Sam as he embarks on his own personal mashup of I Am Legend and Dawn Of The Dead, trying to keep himself busy while barricaded in a vintage Parisian apartment building with only the zombified corpse of an old man he dubs Alfred (the ever expressive Denis Lavant) for company. The Night Eats The World isn’t especially concerned with the particulars of where the zombies came from, or how they spread—although Alfred becomes a zombie after committing suicide, so clearly this is more of a Romero-style “living dead” scenario than a 28 Days Later-style virus—and instead devotes its attention to the intimate details of Sam’s daily routine. To Rocher’s credit, this is not nearly as tedious as it sounds.

Befitting a film more interested in the existential questions raised by an army of undead monsters than in the carnage wreaked by same, the effects makeup and cinematography are both unfussy but skillfully executed, and the flesh-crazed horde itself is framed and choreographed in some strikingly artistic ways. But although it’s admirable to make a zombie movie with more on its mind than graphically chomping on some poor schmuck’s guts, the filmmakers’ attention could have been more focused on the practical matter of nailing the film’s multilingual approach.

About that: Considering Lie is alone on screen for much of the movie, the dialogue in The Night Eats The World is minimal. Thus, the film was shot with both English and French dialogue, with alternate takes spliced in to create a French and an international version. We haven’t seen the French cut, but although Lie does his best with the rather stilted English dialogue in the version screened for critics ahead of its U.S. release, it’s obvious that he’s not entirely comfortable doing it. (Parisian-by-way-of-Iran actress Golshifteh Farahani, who shows up late in the film, is much more natural. But she’s done quite a few American movies.)

Combined with the repetitive structure (a man can only be startled by an unexpected noise so many times before the surprise wears off), this critical weakness threatens to overwhelm an already slight film. In the end, though, it’s the very concepts that make The Night Eats The World sound insufferably pretentious on paper—namely, its high-minded ideas and emphasis on small moments—that tip the film toward intriguing rather than, well, zombifying.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.