A brief history of live-concert bootlegging

People have been making recordings of performances by musical artists without their knowledge or permission for years, but the first recognized, wide-release bootleg to hit the underground-store shelves came in the summer of 1969. Titled Great White Wonder, it was released by Trademark Of Quality Records, a label set up by a couple of guys in Los Angeles, “Dub” Taylor and Ken Douglas. The album was composed entirely of unavailable and unreleased recordings Bob Dylan had made over the previous eight years, including a number of cuts he recorded with The Band that would become part of the Basement Tapes.

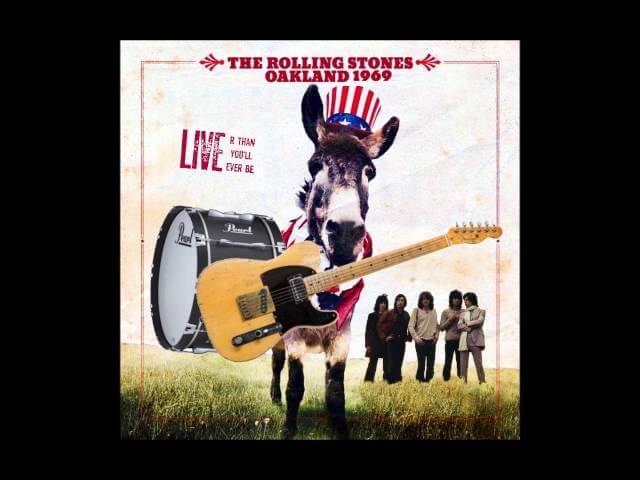

Trademark Of Quality was the forerunner to the wider bootleg recording industry, and within months of debuting Great White Wonder, it ventured for the first time into the live-concert realm, issuing releases that are still venerated and passed around. Among its more notable selections include a Rolling Stones show in Oakland in 1969 titled Live’r Than You’ll Ever Be, Led Zeppelin at the L.A. Forum in 1970 released as Live On Blueberry Hill, and In 1966 There Was, a near-complete recording of Bob Dylan’s famed show at the Royal Albert Hall, where he deafened those who would call him “Judas” for his Stratocaster-strapped electric turn.

Other bootleg labels soon began popping up. Rubber Dubber Records issued an outstanding Jimi Hendrix double-LP titled Live At The Los Angeles Forum in 1970, Rock Solid Records was responsible for Led Zeppelin’s 1977 near perfectly recorded Forum gig Listen To This, Eddie!, and the Amazing Kornyfone Record Label, one of the most prolific names in the game, issued more than a hundred different titles between 1974 and 1976.

As the ’70s wore on, the bootleg record industry exploded. New labels popped up almost daily, offering wholly new recordings, remastered retreads of what was already out there, and different compilations of the best tracks from a multitude of performances. The morass grew so large and intractable that Kurt Glemser, a live-concert obsessive out of Ontario, felt spurred to release the bible of bootlegs in 1975. Glemser’s Hot Wacks helped consumers get a handle on what was out there, what was good, and what wasn’t worth the vinyl or tape that it was printed on. To the underground enthusiast, Hot Wacks served as a necessary and vital compendium, one that Glemser regularly updated throughout the years to help others to navigate their way through the hellish tangle of the expanding black market.

A bootleg recording makes its way out into the open market through a variety of different ways. In the early days, the best releases came from ill-gotten soundboard recordings commissioned by the band members themselves for potential official release at some point in the future. These recordings had the benefit of multiple, carefully placed microphones placed in front of every instrument, fed into a soundboard, and monitored by a hired engineer, like the great Eddie Kramer. Creating a record from this method required a great amount of wheeling and dealing between bootleggers and those who had access to the tapes themselves, or in some instances, outright theft.

Another technique that produced tapes of highly sought-after quality was the FM radio rip. These were live transmissions taken directly from a mixing board and broadcast out to listeners who had a finger placed on the big red record button on their home stereos. But while there are a wealth of soundboard and FM recordings out there, the lion’s share of what’s available came from regular people taking it upon themselves to tote along a concealed recording apparatus to a show on a given night and trying as best they could to capture it for posterity. The identities of these various concert cowboys are rarely known to the listener, but some did manage to achieve a degree of notoriety, like the legendary Mike Millard.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.