Nostalgia for so-called “retro games” has been kicking around since the late ’90s, so it might seem shocking that the best-selling home video game for much of the 1980s didn’t get an official rerelease for over 40 years. It becomes less surprising when you learn that that game is the Atari 2600 version of Pac-Man—a massive hit when it came out in 1982, whose sales quickly fell off a cliff once players saw how different it was from the arcade game, and whose ultimate failure has long been viewed as a major cause of the American video game industry crash of the mid ’80s. Even beyond games, there aren’t many works in movies, music, TV, or any other medium with a rep as toxic as this weird version of Pac-Man.

Despite its notoriety, and despite being pointedly ignored by Atari and Pac-Man developer Namco for over four decades, this particular Pac-Man received not one, but two rereleases over the last few weeks. (Ostensibly, it’s in tribute to the character’s 45th birthday; yeah, Pac-Man celebrates birthdays. With parties, and everything.) On October 31 a new cartridge of the game (bundled alongside a far more faithful version made this year for the Atari 7800 hardware) was released for the Atari 2600+—a new system that’s a working recreation of the Atari 2600 with modern upgrades, the ability to play Atari 2600 and 7800 games, and, if you buy the new Pac-Man Edition, a snazzy yellow color scheme.

And then, two weeks later, the 2600 version of Pac-Man was one of a whole crop of Namco Atari ports added to Atari 50—a playable history of the company (available on PlayStation, Switch, Xbox, and PC) that includes dozens of games and several hours of original and archival documentary footage—as part of the Namco Legendary Pack add-on, which also features new interviews with former Atari developer Tod Frye about his adaptation of the game. It was far from the biggest gaming news of either month, but it’s still surprising to see this particular version of Pac-Man get any attention these days, much less two rereleases in two weeks, after decades of being pacmana non grata.

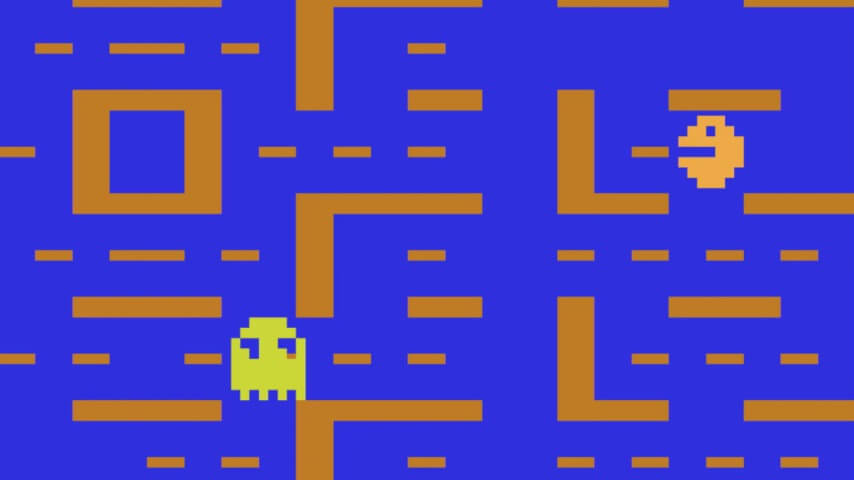

Don’t call it a redemption tour, though. Although Frye’s game isn’t quite as catastrophic as its legacy, it does need to be taken fully on its own terms, and situated within the context of its era, to be appreciated. If you expect it to resemble the arcade game all that closely, you will most likely be disappointed. In some ways, it feels like a cover of Pac-Man played by somebody who downloaded the tabs without ever listening to the original. It has a maze filled with dots, of course, and four ghosts chasing a ravenous circle that occasionally, fleetingly, chases them after eating an especially big dot, but nothing looks or feels quite right. The arcade’s portrait-style screen has been flipped on its side to better fit a home TV, the blue background and orange-brown walls replace the stark simplicity of the original visuals with a design sense that foreshadows Fallout’s jumpsuits, and Pac-Man’s distinctive “waka waka” eating sounds are swapped out with a harsh, mechanical clacking.

As Frye describes in the Atari 50 DLC, the technical limitations of the 2600—a piece of hardware released in 1977, almost three years before Pac-Man made his arcade debut, and five years before the 2600 version was released—greatly hampered what he could do with the game. Still, some of his aesthetic decisions work well; the ghosts’ ephemeral flicker, caused by the extremely small number of sprites that the 2600 could process on any one screen, might have been a major focus of criticism over the years, but it makes them more, well, ghost-like. This isn’t a cartoon-cute mazerunner with comical henchmen, but an ugly, spare, brutalist affair—like a Soviet Bloc Pac-Man—and there’s something perversely fascinating about that.

It might be barely recognizable as Pac-Man, but given what the 2600 had under its hood, Frye’s game is actually impressive. Sure, it’s no Yar’s Revenge—it’s barely even Pac-Man—but if it had a different name, it wouldn’t be considered such a failure. And if Frye was allowed to be more creative with it, instead of trying to follow the Pac-Man script as closely as the 2600 would allow, it easily could’ve been even more impressive. Of course it never would’ve sold 8 million copies without Namco’s quarter-muncher on the box, and Frye himself would’ve lost out on hundreds of thousands of dollars in royalties he earned in the months after its release—and that’s 1983 dollars we’re talking about, when a buck was actually worth something. But the game’s disastrous reputation exists because of the gulf between expectations and execution; if the former weren’t so high, the latter wouldn’t feel so unsatisfying.

Not having any version of Pac-Man on the 2600 would’ve hurt Atari in 1982, but having this specific version—one so unlike the game people wanted to play—perhaps hurt it even more, with this game commonly credited as one of the main factors in the collapse of the 2600 in 1983. Despite selling more than any other video game in history at the time, it was still massively overproduced, with unwanted stock cluttering store shelves long after release. And no game more conspicuously pointed out how technically inferior the 2600 was to the arcade than Pac-Man, which quickly cooled off Atari’s console.

It’s really hard to set aside all of that baggage today and approach Pac-Man 2600 for what it is, instead of what it wasn’t (and what it became). It’s hard-locked as an all-time terrible port that helped kill off the previously booming home console biz in the States for multiple years. And it doesn’t matter that it’s actually a better game than a long list of other 2600 titles, many of which are remembered more fondly today; it’s still so far from what people wanted it to be—from what it needed to be—and is so defined by its failure, that few will give it the benefit of the doubt. 43 years of “worst game ever” claims make it hard to see it any other way.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.