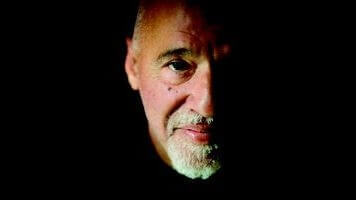

Paulo Coelho gives Mata Hari his superficial treatment with The Spy

Margaretha Zelle, better known to history as Mata Hari, was a crucial cultural figure in early 20th-century Europe. She was a courtesan and a libertine, a famed exotic dancer whose scandalous comfort and openness with her body made her both an icon of sexuality and a target to an old-world order that couldn’t comprehend of a woman with her boldness. In 1917, on evidence that was dubious at best, willfully ignored otherwise, she was tried as a German spy and executed.

Having lived one of the most dramatic lives imaginable in an intensely exciting period, it isn’t surprising that Mata Hari has retained her cultural currency for almost a century after her death, most famously with a Greta Garbo film from 1931. Her life, or at least the popular story and legend surrounding it, combines sexy wartime intrigue with a bold and unapologetic woman—either a cunning navigator of the patriarchy or a devious and manipulative femme fatale, depending on your point of view—the kind of character whose struggle will feel modern so long as strong and independent women are looked upon with hostility.

What is surprising, however, is that the artist to resurrect her for 2016 is Paulo Coelho, whose novel The Spy takes the form of letters from Hari to a lawyer, written as she awaits her end in jail. Coelho, a dime-store philosopher whose work is beloved by those who find motivational posters motivating, hasn’t written a thriller with The Spy, nor is it a feminist manifesto or bit of scholarly history. (At 184 tiny pages it is roughly as illuminating and informative as a skim through Hari’s Wikipedia page.) Instead, it’s merely the latest of Coelho’s surface-level narratives to be stitched over with “insights” that only sound profound if you’re not really paying attention. “Honesty has a way of dissolving lies,” someone says at one point. (Perhaps it sounds more poetic in the original Portuguese; the translation was done by Zoë Perry.)

In fairness, Hari isn’t a bad candidate for the big-picture-at-the-expense-of-details treatment. Her performances, where she claimed ties to Asian and Egyptian cultural traditions, fit neatly into Coelho’s “we are all one soul” worldview. (“I was nothing, not even my body,” she says of being undressed on stage. “I was just movements communing with the universe.”) And by presenting her beliefs on sex, her body, and self-expression as immutable cosmic truths, he suggests a reasonable explanation for her blasé view toward societal constraints, even when violating those norms put her in danger.