The Big Cigar review: Black Panther history gets a Hollywood makeover

The improbable story of Huey P. Newton’s escape to Cuba—with the help of a pair of movie producers—is stretched thin in this Apple TV+ miniseries

At the heart of The Big Cigar, the Apple TV+ miniseries centered on Huey P. Newton’s escape to Cuba aided by a pair of Hollywood producers, is a simple, oft-repeated idea: This entire thing could be a movie! Bert Schneider (played by Alessandro Nivola) means this literally. The lengths he and his producing partner, Stephen Blauner (P. J. Byrne), go to help the Black Panther founder flee the United States are improbable—seen only in the kinds of indie movies these trailblazers were churning out in the 1960s. And it’s only by pretending to get one of their projects off the ground that Schneider is able to help Newton, Hollywood serving as a helpful shield for the outlandish things these men have to do. And Schneider does believe what they eventually get away with could, indeed, make for a great Hollywood flick.

The problem with this show (which premieres May 17) hitting that note over and over again is that you’re reminded that those Hollywood heydays are over—and that, these days, such movie-ready plots end up serving instead as premises for prestige-TV dramas. There is nothing inherently wrong with these. But there are times when, over the course of its six episodes, The Big Cigar feels like it could’ve used a trim, a tighter container, and, perhaps, benefited from being a movie and not a limited series.

“The story I’m about to tell you is true,” Newton (André Holland) tells us in voice-over at the start of the show’s first episode. “At least, uh, mostly true—at least how I remember it. But it is coming through the lens of Hollywood, so let’s see how much of my story they are really willing to show.” It’s but one example of the way The Big Cigar wishes to wink at us at every turn, reminding us this is not history as it happened so much as history as it is retold—through the specific vision of a pop culture object, one whose very biases will be laid bare throughout. Newton is right to be wary. The Black Panther party has long had to contend with the ways in which its very existence has had to struggle against the idea (in politics and in media) that it was a militant, terrorist organization that posed an unimaginable threat to the United States. And it was indeed militant, as its tenets were based on emboldening African Americans to defend themselves from a hostile white establishment and its attendant law enforcement.

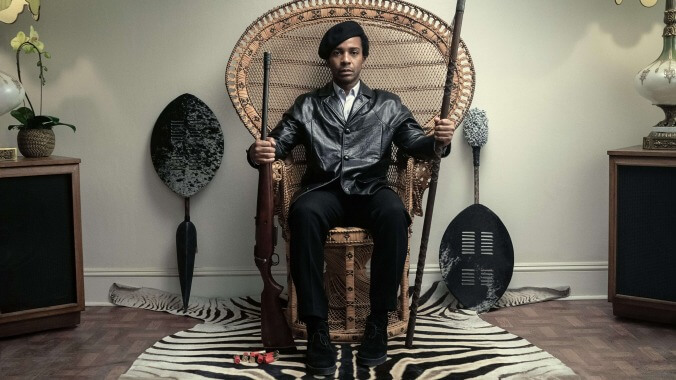

Newton was at the forefront of that struggle. In The Big Cigar, he’s presented as a vexing figure, full of contradictions, who tried to help the Black community in Oakland (and in the U.S. writ large) but who found, time and time again, obstacles toward making that happen. And this is all while images of him with guns and the intentionally abrasive uniform that made the Panthers so easily spotted added to the painting of him as a criminal. By 1974, when charges for the death of a young sex worker are brought against him, Newton turns to the one unlikely ally he’d made years earlier: the producer behind Easy Rider. Schneider was committed to changing the world of the movies but also the world more broadly.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.