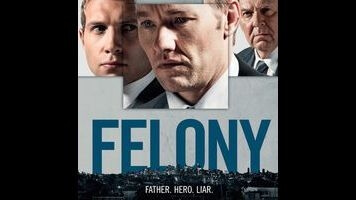

That sense of intense naturalism carries over into the film’s primary moral dilemma, at least for a while. Driving home drunk after celebrating the bust, Mal accidentally clips a kid on a bicycle with his passenger-side wing mirror, knocking him unconscious. (Saville shoots the moment of impact so glancingly that it’s not even initially clear what happened—an inspired choice.) Speaking to the paramedics, Mal impulsively lies, claiming that he arrived on the scene and found the boy already lying there. Detective Carl Summer (Tom Wilkinson, doing a passable Australian accent except when he’s shouting), who knows Mal, is more than willing to cover for him, intentionally circumventing a forensic analysis of Mal’s car and providing him with a better cover story. Carl’s rookie partner, Jim Melic (Jai Courtney), however, is immediately suspicious, and his dogged investigation only intensifies Mal’s feelings of guilt, especially once the boy dies after several days in a coma. If Mal thinks that Carl will let him confess, though, he’d better think again.

Felony was written by Edgerton—a rare instance of an non-directing actor writing a screenplay by himself from scratch—and it’s impressively pointed early on regarding the code of silence that enables police corruption, even among fundamentally decent officers. For example, there are no repercussions when Mal cold-cocks the guy who shoots him in the opening scene (even though the perp is already in custody and is actually apologizing at the time), and cops at a DUI checkpoint look the other way when Mal shows them his badge and provides a password, which is how the accident happens in the first place. Courtney is perhaps too dully noble as the crusader for justice, but Jim’s zeal is nicely balanced by Carl’s self-interest, which he effectively disguises as pragmatism. Every scene between Edgerton and Wilkinson crackles, with both actors digging deep into badly flawed men whose crimes aren’t driven by malice.

Unfortunately, Edgerton the writer creates a situation so thorny that he can’t find a way out of it. Felony’s final act is a complete mess, pivoting on a convenient medical emergency that pushes the narrative in an overly schematic direction. That’s in sharp contrast to the first half of the film, which pulses with life precisely because it’s so damn messy. In the end, the necessary reckoning gets imposed upon the characters, rather than emerging naturally from their triangulated confrontations. And the final scene, which seems meant to leave the movie suggestively unresolved, comes across instead as merely cute. The danger of closely mimicking real life is that real life is seldom satisfying. Stories are designed to lead from chaos to order, but this one starts out so chaotic that it winds up having to cheat in order to get there.

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)