Nintendo's Baseball History: Why Ken Griffey Jr. and the Seattle Mariners Should Be Honorary Smash Bros.

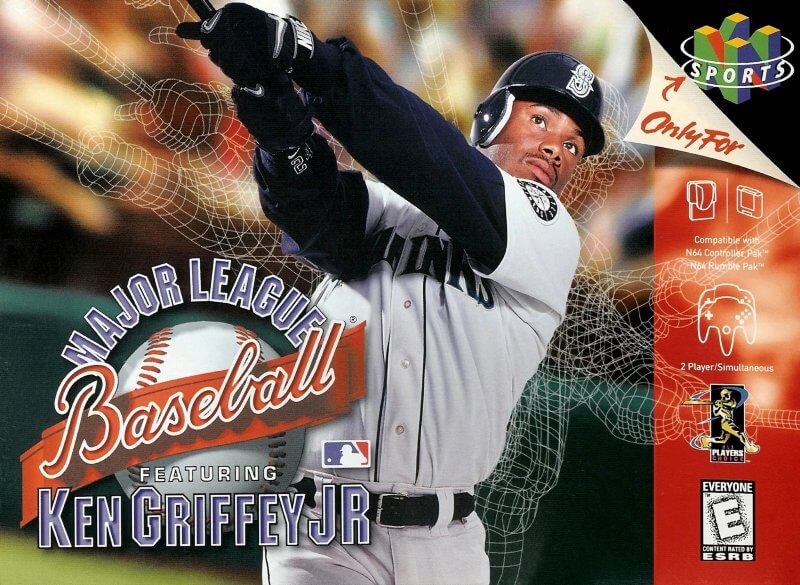

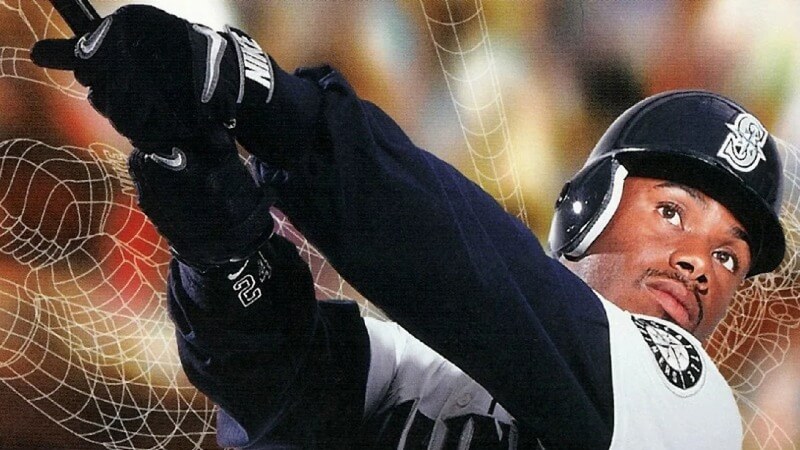

Images: Major League Baseball Featuring Ken Griffey Jr. box art

The Seattle Mariners made it to MLB’s postseason in 2025, which, if you aren’t a baseball fan, is not a thing that regularly happens. They had last made it to the playoffs in 2022, which was the first time that the M’s had done so since 2001. Just for a little context: one of the better players on this year’s team, Julio Rodríguez, wasn’t even a year old yet at that point. For further context of what it’s like to be a Mariners fan most years: the 2001 Mariners tied a record with 116 wins, and then lost in the playoffs before they even made it to the World Series. The franchise has existed since 1977, and is the only one to not have even made it to that championship round.

This isn’t supposed to be an exercise in beating up on the Mariners, but simply to provide some background on their whole deal. There was a time when Seattle was in the playoffs pretty regularly: from 1995 through 2001, the Mariners reached the postseason four times. (It used to be much more difficult to make it to the playoffs since there were fewer spots within them; four times in seven tries back then was pretty great.) They were easy to like back then, as they had, at various times during that run, legendary and popular players like Ken Griffey Jr., Alex Rodriguez, Edgar Martinez, Randy Johnson, and Ichiro Suzuki on the roster. And who doesn’t love Jay Buhner? (I had a lovely alternate, off-white Mariners hat back in the ‘90s thanks to just how cool that team was to a kid. Mariners appreciation was infectious!) And Griffey had a little something extra going for him, too: his own run of video games.

Griffey wasn’t the only player to have a video game with his name on it back then. It was fairly common to have popular players grant a license for a sports game back in the ‘90s—Cal Ripken, Roger Clemens, Frank Thomas, and Nolan Ryan all did it, and you even had managers like Tony La Russa and Tommy Lasorda using their names and likenesses to sell video games—but Griffey was a whole other setup for a couple of reasons. For one, this wasn’t just a one-and-done or a known name slapped onto an existing game to sell copies regionally, a la Tommy Lasorda Baseball, but an entire series, spread across multiple systems—the SNES had two, the Nintendo 64 another pair, and the Game Boy Color saw a handheld version of the final game in the Griffey franchise. More on those in a bit.

Second, the reason there was a series to begin with was because of who was releasing those games: Nintendo. At the time that Ken Griffey Jr. was playing for the Mariners and these games were being released, Nintendo of America owned a significant stake in the team, purchased in 1992 when the club was thought to be in danger of relocating out of Seattle. Instead, then-Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi offered to buy the team for $100 million. As the story goes, it’s not because he cared about baseball so much as that the community enjoyed the Mariners, and Nintendo—which had their American operations based in nearby Redmond, Washington—was part of that community. And he wanted to give something back to the rest of them considering their support of Nintendo over the years. A generous gift, for sure, even if Nintendo and Yamauchi knew they were likely to make their money back on it given that’s the nature of these things. And owning an MLB team would look pretty great for Nintendo, too.

Major League Baseball didn’t mind the Mariners staying in Seattle instead of relocating—they were sued the previous time the team that became the Milwaukee Brewers, the Pilots, left Seattle after one season, which is how the Mariners came to be in the first place—but they did not appreciate that a Japanese businessman and Japanese company were coming to their rescue. Listen, 1992 wasn’t that far removed from a decade in which any Japanese-looking art on video game boxes was replaced by something with more western flavor, in order to hide its origins from a public voting Ronald Reagan into office on purpose not once, but twice. So of course there was pushback to a company from Japan opening their wallets for a piece of America’s pastime. You don’t need me to tell you that there was panic over whether or not Japan was going to buy up everything American and make it theirs because one company wanted to buy an MLB team, unless it’s your first day learning about America.

While Yamauchi had initially offered to put up the entire $100 million necessary to buy the team (even back in 1992 his net worth was thought to be north of $1 billion, and he had plenty of stock in Nintendo to sell, too) he was instead forced to continually drop his stake and add more and more other local business people—more local than he was in MLB’s eyes, if you catch my drift—until the stake that a Japanese company had in the club was under 50 percent. Meaning, not a controlling interest. This despite the fact that Yamauchi was going to have Nintendo of America’s president, Minoru Arakawa, as the point person running the team. Arakawa had lived in Washington for 15 years already at that point, per reporting at the time, and had co-founded Nintendo of America in 1980.

MLB’s original position—straight from then-commissioner Fay Vincent—was that there was basically no chance of the offer being accepted, due to a recent unwritten agreement among the various teams that owners outside of North America were not going to be allowed into their ranks. When it became clear that the league didn’t really have a leg to stand on here—Arakawa had lived in the United States, and the Seattle region specifically, for too long to not be considered local unless you wanted even more editorials about how this was at best xenophobia from MLB, a whole bunch of other local business leaders had joined on to the bidding group, and oh there also wasn’t another ownership bid anywhere near as strong as this one to go to for what was a time-sensitive matter—they relented. Nintendo didn’t own a majority of the Mariners, but they owned more than anyone else did.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.