This shambling ouroboros of town-wide confusion, anger, and pain is a ritual Americans perform over and over again, each time someone decides to take a gun and open fire in a place where they think they’ll do the most damage. It’s a metaphor that sounds through Weapons like an ominous mourning bell; to make sure we get it, Cregger even projects a giant assault rifle into the skies of Archer’s nightmares. Rifles just like that one hang over all of us, every school, every concert hall, every shopping center, every government building, whether we can see them or not.

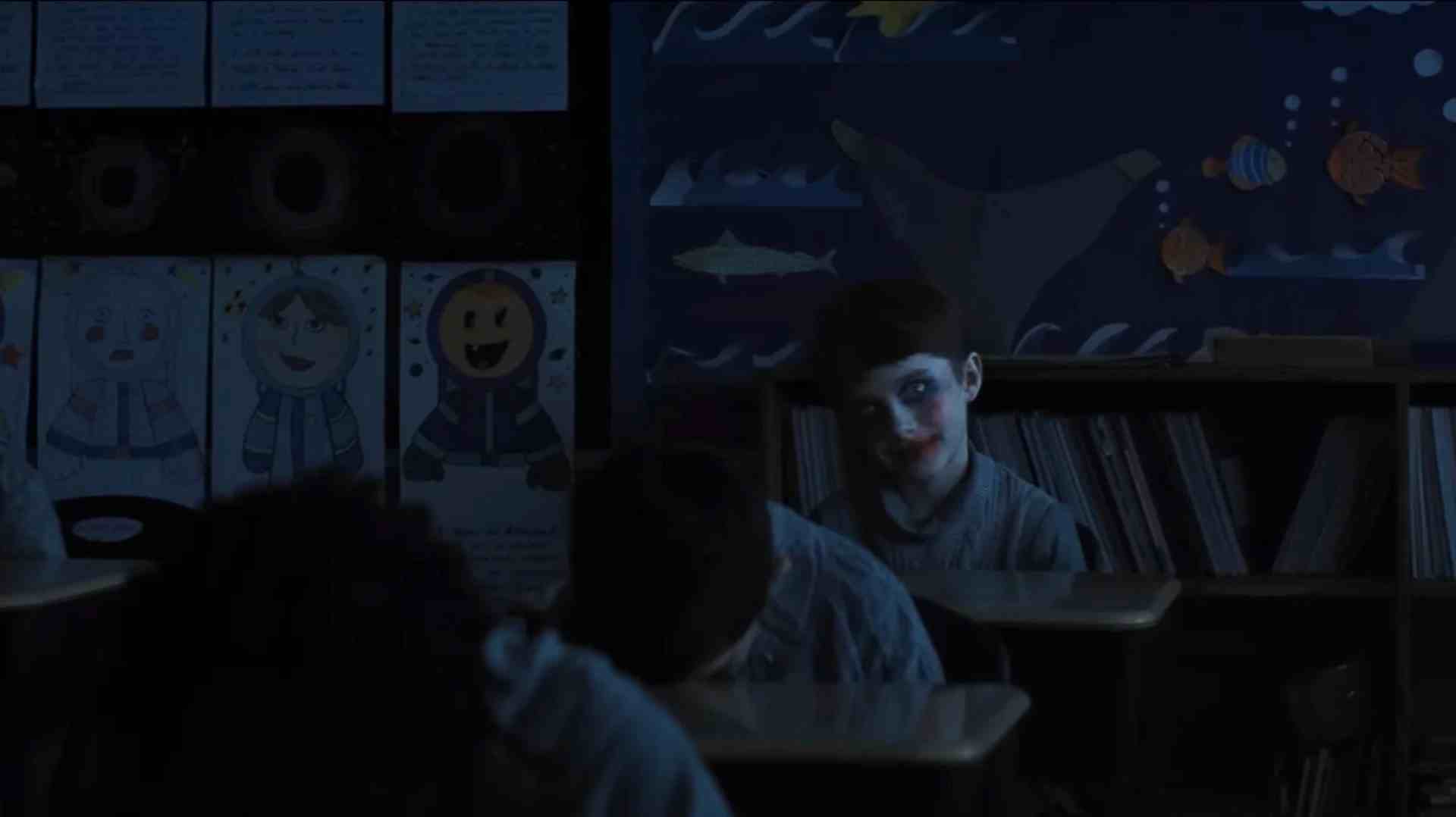

But Weapons is not content to coast on the “supernatural mystery as school shooting” metaphor. What makes the film really work is Cregger’s decision to leave the kids, for almost the entire film, standing stock-still in a basement, under the influence of an actual witch (a sublime Amy Madigan) who’s taken them via blood ritual for her own purposes. With a couple of exceptions, we do not learn the children’s names. We do not come to recognize their faces or their hobbies. They are a monolith, a shadow over an entire town, an entire country.

And what do the adults do in the shadow of this monolithic loss? They turn on each other. They drink, they shout, they have torch-and-pitchfork meetings where they ignore grief counselors and snarl at school administrators. Cregger breaks the melee up into chapters, each focusing on a different link in this ever-growing chain of misery, and the more individuals Weapons follows, the more it becomes clear that this rage and pain isn’t about the kids at all. It’s about the adults and their excuses, their cruelties, the blows they can land in the blame game.

While the adults are doing this, of course, there is another victim just waiting for someone to pay attention. Alex (Cary Christopher), the lone child from Justine’s class who didn’t vanish, is not just dealing with survivor’s guilt, but living in an entirely different hell, one he doesn’t feel safe revealing to anyone. His “Aunt” Gladys (Madigan) has stolen these children in order to drain their vitality, and is now holding Alex and his parents hostage. The other kids may have disappeared, trapped in a trance state, but Alex’s entire world shifted overnight into something else. He’s left to care for zombies, spooning can after can of soup into lifeless mouths. He’s clearly in pain, yet for much of the movie no one (with the exception of Justine) seems to notice or care. He’s moving on, they think, as they move him into another class and stop asking questions. Meanwhile, like a kid who survived a mass shooting only to be shoved in front of cameras, used as a political talking point, or—in an increasingly common occurrence—live through another, Alex is trudging through the waste left behind by the neglect of adults.

Many Americans would rather spill more blood, use up the young in service of maintaining some semblance of “the good old days,” and make excuses instead of pursuing the easy solution—that’s why assault rifles hover over our nightmares and pristine empty classrooms conjure up images of tragedy rather than potential. Survivors are driven into a corner where they’re simultaneously scapegoats and heroes, while those around them argue over the how and the why instead of the what’s next. Decisionmakers assign blame and look for motives, turn to buzzwords like “door control,” instead of admitting that this society values the status quo over a roomful of children. The kids in Weapons, the ones actually lost to this mystery, do not get a voice. The adults speak for them, about them, around them. They’re not humans, but talking points, just like the kids used as excuses to ban books, to arm teachers, to police bathrooms. The U.S. is all but numb to the idea of losing kids to violence—so used to the arguments and the counterarguments and the wielding of “politicizing tragedy” as a cudgel against progress—that we barely stop to talk about the kids themselves. All of this pulses through Weapons like blood from an open wound.

Cregger does not turn the film into a sermon, but he does lean towards cooperation, as enemies-turned-allies Archer and Justine fight to save these children from a fate worse than death. Thanks to Alex’s courage and ingenuity, the kids even get a glorious moment of agency in the end, allowing them to literally rip their captor to shreds, to tear down the old to make way for the new. (They become weapons in a very different sense.) But the film’s final words, an observation that “some” of the kids could eventually speak again after their ordeal, leaves Weapons in an honest, haunting, liminal space between endings and solutions. Nothing is really fixed. The film does not end with rescued kids so much as salvaged kids, bodies are strewn across town, and no one will ever be the same; according to the opening voiceover, nobody will even admit what happened. When it comes to tragedies involving children, particularly those that unfold in schools, this is often how the national conversation goes. No ending, no closure, not even the start of some new great debate. Just another untreated wound, left to scar, until the scar tissue builds up so thick and impenetrable that there’s no feeling left. The lasting horror of Weapons is the persistence of that numbness. In a film full of recognizable bits of American life, it’s what rings the truest.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.